Denis Villeneuve x4 – Arthouse freak at Hollywood

The long-awaited new version of Dune is about to have its theatrical release – another attempt to screen a series plagued with bad luck (Lynch’s version turned out to be a parody, Jodorowsky had to settle for a documentary). How did the Canadian director dare to take on this project? Denis Villeneuve seemed to be the only possible candidate, after appearing to expand his ambitions over the past years (what does it matter that Blade Runner 2046 was rather an atmospheric dud?). Despite the obvious differences between the way the Canadian film industry works versus the limitations that Hollywood directors face, I went through all of Villeneuve’s films, trying to decipher his mechanisms. I put together a short list of four films from different eras of his oeuvre, all defining in extremely varied ways. It would be easy to say that Villeneuve started with love for Godard and ended up making Tarkovskian films – his journey is not as hyperbolic as it seems.

Un 32 août sur terre (1998)

Villeneuve’s debut is a romance very close to a nouvelle vague pastiche: the Jean Seberg poster hangs proudly on the protagonist’s bedroom wall. The film is about two poor souls that love each other, but can’t find a way to confess it; their precipitous, spur-of-the-moment lifestyle doesn’t flow naturally, rather is marked by adrenaline. It’s 1998, which is exactly when Run Lola Run came out, another time-dependent film. Only that in the case of 32 août, the clock is somewhat biological: she gets into an accident that propagates her in an existential crisis, which she only knows how to solve by having a child; he is her best friend, naive and enthusiastic, who secretly loves her. While shyly dancing around the subject, he agrees on being the child’s father on condition that their act of love takes place in the desert, outside of civilization. Once they get there, it becomes clear that it’s nowhere near the lush debauchery in Zabriskie Point; the taxi driver abandons them right away and while wandering around, they discover a charred corpse in the bushes. Two things strike, for starters: 1) the formal vivacity with which Villeneuve makes jump cuts, fast cuts, fast-forwards; it is essentially a film that simultaneously abuses the legacy of Godard and the tricks offered by digital technology; 2) Villeneuve will no longer make movies like this one, or the fact that this film, in particular, has none of the so-called Villeneuve motives. Even so, I was able to identify a few: the thing for posters (also met in Polytechnique, Maelström, Enemy, and, of course, Blade Runner 2046), the obsession with moving back and forth through time (also seen in Polytechnique). To a greater or lesser extent, Villeneuve is a shocker (whether we’re talking about violence on screen or building a staggering sequence; it’s pretty obvious that he likes characters covered in blood) – something that he achieves through editing. Take the final scene in this ill-proportioned film, for instance, when it looks like the two fools finally realize that they’re meant to be together: rushing towards her, he ends up at the hospital in a coma after some guys beat him blind on the street.

Villeneuve’s endings are always abrupt – the action is left hanging, only suggested or cut short on purpose, precisely so that the final resolution doesn’t make it to the screen (in Blade Runner 2046, the father-daughter reunion is interrupted when he reaches the glass walls behind which she is isolated, in Prisoners, it all goes black at the whistle sound heard by the police officer; probably the most discussed of all is Enemy itself, which ends with a huge spider that looks the protagonist in the eye).

Maelström (2000)

Villeneuve’s following film is an even bigger surprise. Despite its imperfections, which obviously derive from lack of practice, it’s probably the most creative and shameless of all. I will point out its best assets: 1) it’s narrated by a dying fish, whose somewhat academic speech is interrupted by the butcher who cuts off its head; 2) Villeneuve throws some uplifting pop music over a bloody abortion; 3) the poetic-mystical intertitles that announce that Norwegian fishermen use music waves instead of nets. Everything we see on the screen seems to be nothing less than the product of the protagonist’s twisted mind; the impressionism of the film stems from the guilt she feels after running over a man fatally. Here, Villeneuve really seems to pile into a mystical-fishing delirium all the things he will never use again. As proof, the son of the man she had just killed tells her jokingly that what killed his father is a Haitian voodoo curse, not a car; two minutes later, over the belly of a dead fish, a butcher announces that the father’s killer will surely die, and those gathered around him work out how the death will happen, while raising a glass.

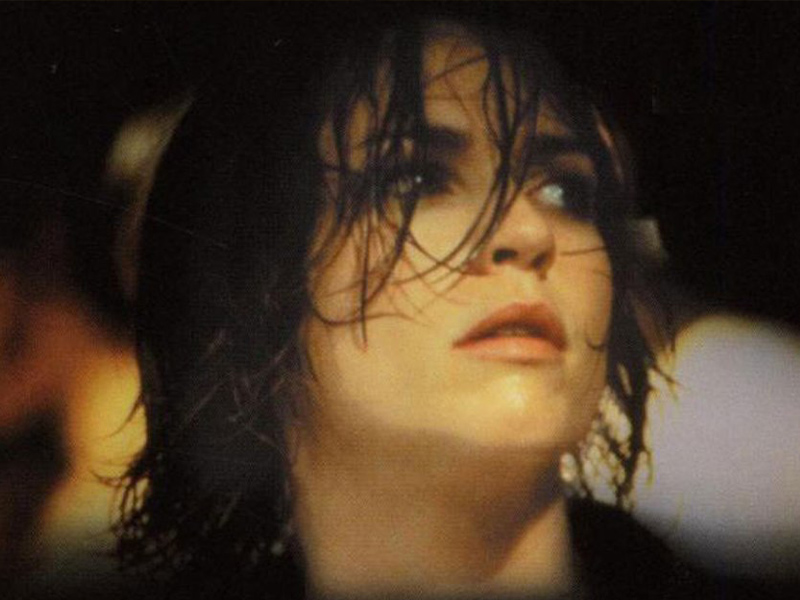

Enemy (2013)

With Enemy, an adaptation of Saramago, Villeneuve crosses over for good to the side of Hollywood cinema, although he is still showing signs of resistance. Here, Jake Gyllenhaal plays in a double effort a confrontation between the subconscious and the conscious, which unfolds on the sounds of a very Hitchcockian music. The similarities with Vertigo/Psycho are plenty – the protagonist has a phobia about losing control. In his hallucinations, he sees women dominating the city, stretching their huge limbs over it (similar to how, in another scene, a giant spider climbs the city’s skyscrapers). The film is nothing more than a depiction of a guy’s fear of commitment, who doesn’t reconcile at all with the pregnancy of his wife – his confrontation is with a presumed alter ego (taking in a physical form) who has all the attributes he lacks. Again, we are talking about another existential crisis, only this one has ultra-metaphorical overtones; no matter how he spins it, he finds himself in a loop in which he lets himself be carried away by temptations, alternating between two possible characters. Enemy announces the chromatic expressionism that will dominate Villeneuve’s later films (the obsession with toxic yellow, for example, which floods the desert vastness in Blade Runner 2046, also to suggest how isolated man is in the nothingness around them), as well as the relinquishment of the pop soundtrack that comments in tandem with the image (see the obsessive use of Radiohead’s music on key moments in Incendies, or Tom Waits’ music in Maelström).

Arrival (2016)

I had noticed a certain pattern in Villeneuve’s screenplays, a certain MacGuffin-type hook that solves the narrative and closes it in a loop: the first, in Incendies, when the three points tattooed on the abandoned son’s foot, whom the protagonist never ceases to look for all her life, pop right in front of her eyes when she comes out of a swimming pool; the second, in Sicario, when we finally find out why it was necessary to see a police officer wake up every morning, without his world crossing paths with that of the protagonist. In Arrival, Villeneuve tampers with the linear narrative he had gotten us accustomed to before (so, again, we’re in for a surprise) in a hyper-sophisticated form, which, no matter how demonstrative, is spectacular to the end. In short, once a linguistics expert comes to master the language of aliens, she also manages to manipulate time; the film is edited so as to look like a film based on continuity (it begins with the relationship between Louise and her dying daughter; therefore, the alien invasion seems to happen years after this event). It would be easy to say that it’s the other way around, because, here, time is a volatile notion, which works according to a different set of rules. Unlike a film that relies exclusively on spectacle (see Interstellar), Arrival has a twist that doesn’t require the help of science in argumentation, but is guided only by the idea of giving the chills – and when it comes to emotional manipulation, as we have seen, Villeneuve rules.

Journalist and film critic, with a master's degree in film critics. Collaborates with Scena9, Acoperișul de Sticlă, FILM and FILM Menu magazines. For Films in Frame, she brings the monthly top of films and writes the monthly editorial Panorama, published on a Thursday. In her spare time, she retires in the woods where she pictures other possible lives and flying foxes.