Dok.cetera: November’s Documentary Recommendations

In the throes of autumn’s documentary festival season, Dok.cetera brings five more non-fiction selections to recommend. This month’s selections look at two very different films that have made waves on the festival circuit everywhere, from Ji.hlava to IDFA. We also look at three films currently streaming, including the return of master documentarian Robert Greene, as well as the latest from one of Africa’s most important young filmmakers. Finally, also streaming, we look at a poetic, speculative documentary on the nature of the now.

On The Circuit

Babi Yar. Context (dir. Sergei Loznitsa) – Ukraine, The Netherlands

In the autumn of 1941, 33,771 Ukrainian Jews were executed by the German army with the assistance of state and supplemental police. Their bodies were disposed of in the vast Babi Yar ravine near Kyiv. These events, never officially documented, have been meticulously researched by master documentarian Sergei Loznitsa in his latest film, Babi Yar. Context. In researching several Russian and German archives, Loznitsa reconstructs this historical event of World War II tragedy with an undeniable intensity, altering collective memory in the process.

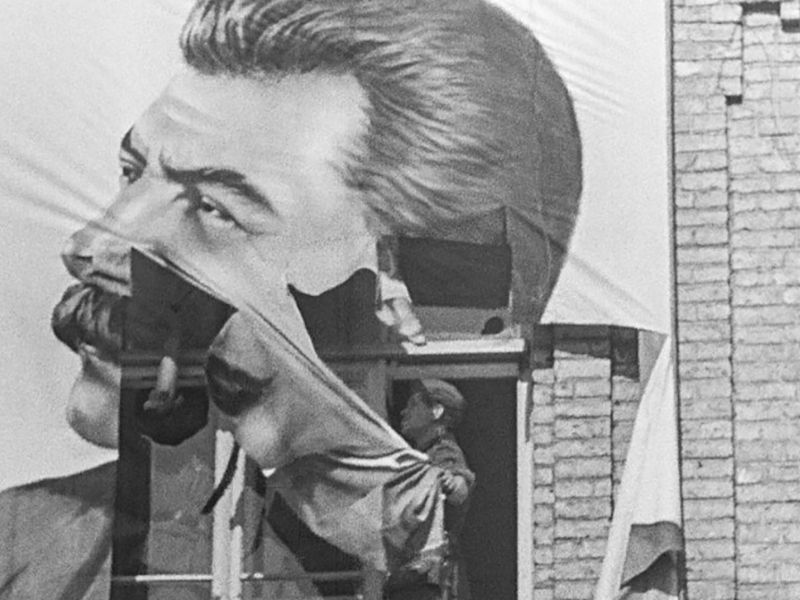

We would be remiss in knowing that, much like Romania, German soldiers were welcomed in Ukraine during their initial march into the country. Huge celebrations took place around the country, with pictures of Stalin ripped from city walls everywhere from Lviv to Kyiv. In his place, images of Adolph Hitler emerged. The country’s Jewish population was immediately accused of Soviet sympathies. And by 1941, a four-year extermination of some 150,000 began effectively with the Babi Yar massacre. In 1943, Soviet soldiers retook the capital region, Stalin’s posters returned, and the Germans were prosecuted. And, like with the Germans, the Soviet return was also welcomed with open arms by the local populace. Additionally, the Babi Yar ravine was now not looked at as a location of Jewish extermination but as a location of the “brutal extermination of Soviet citizens and prisoners of war”. By 1952, it was buried forever under industrial waste.

With Babi Yar. Context, Loznitsa is able to depict the history and causation of people stuck between two of humanity’s most ruthless figures. It is an archive in terms of how the terror of totalitarianism elicits the darker tendencies of the human psyche. Atrocities are condoned, not just without resistance but also without much thought. Loznitsa has also stated how he has always been interested in this event, not simply from a historical perspective, but what it can teach us about our current place in history. As we see the increased proliferation of authoritarian ideology worldwide, coupled with the social divisiveness of late capitalism, we too may find ourselves stuck existing between two evils. Babi Yar. Context and its immersive narrative from the pre-Nuremberg Kyiv trial to the incredibly intimate personal stories of those involved and affected breaks down the very existence of time as a barometer of truth. This is not about “then”. This is about “then and now” and the practice of “remembering” and reconciling through the artistic process.

“Babi Yar. Context” screens this month as part of the IDFA Masters collection and in Porto/Post/Doc’s International Competition.

The Gig is Up (dir. Shannon Walsh) – Canada

There are a few buzzwords in this era of the twenty-first century, increased through the seemingly endless coronavirus pandemic. One of the most prominent such words may be “gig economy” (more of a phrase than a word, I suppose). We all know the gig economy well. Perhaps we are already working in it. Technically, creative freelancers are part of it, but its traditional meaning encompasses Uber and Bolt drivers, food delivery riders, and various Upwork professionals. This version of the modern economy is worth a mind-boggling USD 5 trillion annually and globally. From China to Canada to the USA, by 2025, it is estimated that some 540 million will make the entirety of their livings via platform-based work (for another, maybe less known example, read up on the dystopia reality of Amazon’s Mechanical Turk platform – named after a late 18th century fake chess-playing machine). Shannon Walsh’s The Gig is Up goes deep into the front lines of this emerging economic reality – providing both the benefits and detriments caused by it.

In terms of benefits, it is obvious why gig work is appealing to many. There is no office, no commute, no hierarchy of position, and there is the absence of most formal (and increasingly outdated) requirements like a university degree, as one gold-teeth having Floridian – and a rare gig economy proponent in the film – proudly proclaims. But for every personal advantage, there is a disadvantage, and, what’s more, those disadvantages metastasize across society, creating huge questions and holes in regards to sustainability and (another buzzword) inequality. The model for the gig economy is to blame – essentially, pull in the personnel (both customer and employee), then systematically cut back on wages as those on the labor side increasingly rely on it. Of course, algorithms are abundant in this process, gauging everything from (buzzword alert) productivity, personality, and the all-important customer-provided feedback. It is an interesting and elusive form of capitalism that all too often relies on technical prowess and social bitterness to sustain a certain, as the film states, “upper middle class millennial” lifestyle. In The Gig is Up, these kinds of stories abound, and in every sector and market imaginable. A few examples include a Yemeni immigrant Uber driver in California who has gradually seen his wages decrease by some 60% or the San Francisco-based single mom who left her promising office-based career for Uber, who now struggles to make even a fraction of her original gig salary. Needless to say, to boot all of this is the complete lack of social protections, benefits, and in many countries, increased taxation on the contract/freelance/gig worker, all while the multi-national rake in billions upon billions, paying barely a tax in the process. As The Gig is Up points out, all this leads to a place where the days of globalized opportunity through market-based approaches have quickly turned from dream to nightmare for many.

“The Gig is Up” screens as part of the IDFA Best of Fests collection.

Now Streaming

Procession (dir. Robert Greene) – USA

American documentarian (and personal favorite filmmaker) Robert Greene has always looked at film as a process. In his films, he uses cinema as a means to process personal history, seeking healing for his trauma-laden protagonists and reckoning from audiences in the process. In his Bisbee’ 17, he had small-town Arizona townspeople recreate the early twentieth-century deportation of its migrant worker population. In his wonderful one-two punch of 2014’s Actress and 2016’s Kate Plays Christine, Green examined the very essence of performance concerning the exploration of female identity, as well as the mythology of celebrity to significant effect. Now, Robert Greene forays even farther into this cathartic place of cinematic reconstruction with the new Netflix documentary Procession.

Procession follows six survivors of sexual abuse at the hands of the Catholic Church. Through a three-year collaboration with reel and a professional drama therapist, they reconstruct scripted scenes about their experience, holding much agency over the ultimate form of the film itself. They decided on the locations, casting and ultimately took roles within each other’s reconstructions. This action in itself creates strong solidarity and understanding, as Greene is then able to withdraw into a more facilitator role instead of a creative driver. The specifics of the story, as is the broader Catholic Church abuse scandal, is well told, and in Procession, the details do not necessarily make up its substance. In the tens of thousands of abuse cases worldwide, the specifics may change. Still, the intent stays the same – systematic abuse relying on the sheer power and influence of the church, ultimately stifling any and all such accusations with the ever-important “statute of limitations” in mind. That is to say, push the ball down the field for as long as possible until time runs out.

In Procession, Greene goes from the localized police force cover-up all the way to the Vatican, both of which publicly denounce the events yet still do little to address them. But it is not justice that Green is after. He, as well as his protagonists, simply seek to alleviate the nightmare of such unchecked power (manifesting itself across society, albeit often in different forms) that still haunts victims decades later.

“Procession” streams on Netflix beginning on November 19, 2021.

Downstream to Kinshasa (dir. Dieudo Hamadi) – Democratic Republic of Congo, Belgium, France

In one of the 2020s most acclaimed and well-traveled documentaries, the young director Dieudo Hamadi’s Downstream to Kinshasa was the first Congolese Official Selection at the Cannes Film Festival. The film is a multi-dimensional work that combines traditional reportage with the excitement and unpredictability of the classic road trip (only in this case, the road is replaced by the vast Congo River).

To set the context, Downstream to Kinshasa effectively begins with the 2000 “Six-Day-War” (not 1967’s Six-Day-War between Israel and many of its Arab neighbors) where, as part of the Second Congo War, some 4,000 were killed (and a further 3,000 injured) in the Battle of Kisangani. This battle resulted from a clash surrounding mineral wealth in the region and included the countries of Rwanda and Uganda. The film’s Francophone title is En route pour le milliard, which translates to “on the road to the billion”. This amount refers to the billion-dollar payouts the Kishnagi people continue to seek from the Congolese government’s role in the atrocities and lays the foundation of Hamadi’s fifth feature documentary.

In 2018, frosted by the government’s seeming indifference to their request (which in actuality hovers around USD 10 billion), about 100 Kisangi travel 2,300 km downstream to the country’s capital of Kinshasa. A homage to persistence and a powerful example of the 39-year-old Hamada’s kaleidoscopic approach to documenting his home country and content, Downstream to Kinshasa reaffirms the strength of community and collective memory. Its empathetic and articulate cast of characters juxtaposes Hamadi’s observational, but no less connected, directorial approach to restructuring memory and trauma, setting the physical river as a metaphor for this personal journey and solidifying his place as one of Africa’s most important filmmakers in the process.

“Downstream to Kinshasa” currently streams on Mubi.

A Hidden Gem

Truth or Consequences (dir. Hannah Jayanti) – USA

There is a town in the U.S. state of New Mexico named Truth or Consequences (for further context, see Kiefer Sutherland’s 1997 Tarantino-esque neo-noir Truth or Consequences, N.M.). It’s a strange name for a place to be called, but it makes sense in the context of the broader American idiom-laden ethos. It refers to the 19th century westward expansion approach and the American myth of exceptionalism: speak the truth or bear the consequences, full stop. Hannah Jayanti’s eponymous speculative documentary – one where she acts as director, producer, cinematographer, writer, and editor, takes this phrase and uses it as the foundation of her illustration of human history. That is to say, the belief in its linear progression; its absolutism.

Truth or Consequences lies somewhere between prophecy and climate action, yet it is a distinct postmodern documentary, covering and questioning the very foundation of post-modernity – the notion that progress is inevitable and that humans can overcome any obstacle, even if perpetuated by the inorganic nature of technology. And, in the face of finite natural resources, to boot. Of course, progress is an imperialist myth formed by the Global North’s pillaging of the Global South. These days this myth presents itself in the form of space travel and planet colonization where a minute handful of powerful people are attuned to it, while the vast majority of those are not – thus, forced continually to exist on a planet devoid of resources in the name of said “progress”. In Truth or Consequences, Jayanti based herself in this peculiarly named town, specifically surrounding the world’s first commercial spaceport – Spaceport America. The town’s primarily white, lower-income American class covers the gamut of ideology (no small task in the ideology-filled country of America). These seemingly simple people opine on their impressions of the spaceport and the very notion of progress, as only they can. They come to terms with their position in the increasingly unequal world and how their very backyard offers some of its most tangible examples.

There is also poetry to Truth or Consequences as Jayanti contrasts past and future through its contemporary protagonists and its dual expositing archival usage and, even, special effects and forward/reverse presentation – juxtaposing significant “accomplishments” with climate damage, transforming the past action into futurist concern in the process. In doing so, Truth or Consequences may subjugate its name and ethos, asking those in the position of modern progress to speak the truth or face the consequences.

“Truth or Consequences” currently streams on Mubi.

"Came to Bucharest after living in Amsterdam & Brooklyn, among others, Steve is the industry editor for Modern Times Review documentary magazine.