Watercooler Wednesdays: The Andy Warhol Diaries & Standing Up

Watercooler Shows, the trending series that everyone talks about the next day at the office, around the water cooler. Watercooler Wednesdays seeks to be a (critical) guide through the VoD maze: from masterpiece series to guilty pleasures, and from blockbusters that keep you on the edge of your couch to hidden gems; if it leads to binging, then it’s exactly what we’re looking for.

This month’s recommendations discuss artistic relevance and fame in different ways. “In the future, everyone will be famous for 15 minutes”, it very well could be that Warhol never said this, but that doesn’t make the quote less Warholian. The Andy Warhol Diaries documents, among other things, the artist’s own need to perpetuate his 15 minutes again and again, always reinventing himself according to the latest trends (which become trendy precisely because Warhol shows interest in them).

15 minutes, on the other hand, is also the standard length of a stand-up set: you get a microphone, a stage, and an audience. In Standing Up – a rather unfortunate translation of the original French title, Drôle – the characters are caught in situations that revolve around these 15 minutes: rising stars, expired legends, or newcomers struggling to make the transition from the amateur night 3 minute-set.

The Andy Warhol Diaries (Ryan Murphy, Andrew Ross, 2022)

In a way, The Andy Warhol Diaries is a posthumous work by Warhol himself. In 1968, the artist is in recovery after being shot, but at the same time, he has to run an expanding commercial-artistic empire. Warhol records all his conversations and hires Pat Hackett to transcribe and archive them. From 1976 until the artist’s death in 1987, the two resume their roles in a daily performance, without apparent end. Every morning at 9 o’clock, Warhol dictates his memoirs over the phone – actually, Warhol tells her about the events of the previous day – and Hackett transcribes them by hand and then types them.

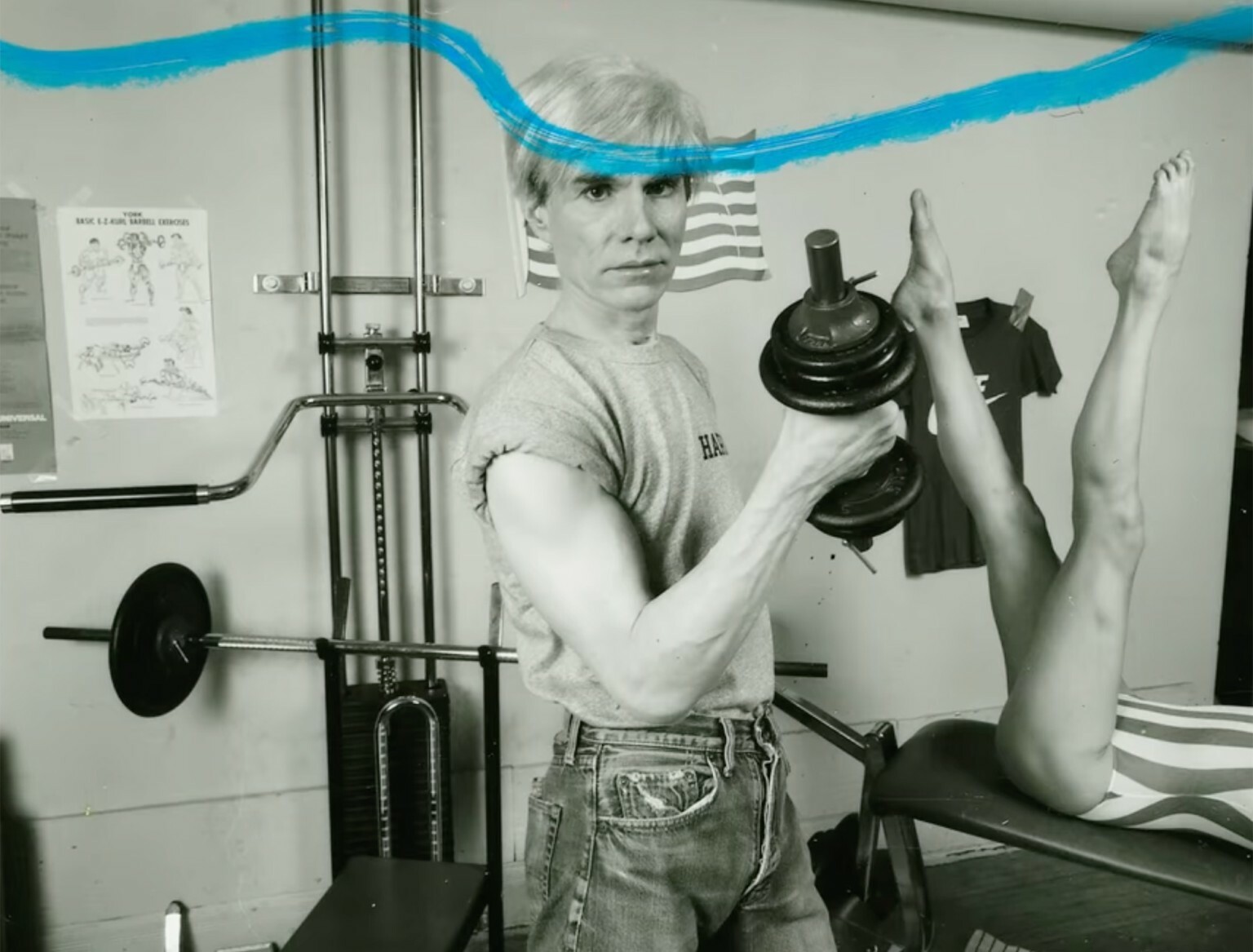

“He could have recorded himself, but he wanted an audience,” confesses Hackett in The Andy Warhol Diaries, the audiovisual version of a book she edited 30 years ago, and whose content had been first handwritten, then typed, and finally printed. It’s a detail that gives insight into Warhol’s own creative process, and the creators of this Netflix docuseries really tap into the methods and lines patented by “The Pope of Pop Art”: repetition, mechanics, standardization, trans-media. In the collective memory and critical reception, Warhol remains best known for his portraits, basically photographs – sometimes Polaroids taken by himself – enlarged, printed on a canvas screen, and then painted.

Covering the last 11 years of the artist’s life, The Andy Warhol Diaries consistently incorporates Warhol’s oeuvre into its stylistic and content choices – drawings, photographs, paintings, movies, TV shows, fashion, computer art, quotes, etc. – and combines them with talking heads (friends, collaborators, curators, and art critics) who contextualize all these things on an artistic, social-political and personal level. Excellent editing, The Andy Warhol Diaries is an intensive course in art history, even when it comes to the redundant informative recaps – each episode reminds us that Warhol was never (really) taken seriously by the high art institution.

The documentary not only interprets and debates his previous work but also promotes itself as a typical Warholian product. For example, it focuses on the cult of celebrity and the obsession with collecting details about the lives of the rich and famous. “People have such a fascination with the little tiny details of what other people do, what they eat, what they drink and what they wear. I suppose if you keep a record of all that trivia long enough – which is all that Andy does in a sense – it does add up to a total picture of our time,” says at one point the editor-in-chief of Interview, a magazine created by Warhol for this exact purpose.

Starting with the 1970s, Warhol shifts his gaze from the underground art scene to the social elite. It’s an artistic bet, but above all, a financial one: Warhol is hunting for new models, more precisely muses who can also act as patrons and buy their portraits for considerable sums of money. There is a commercial interest, but also a genuine fascination and desire to integrate into this world – it’s the American dream for someone who has always been an outsider.

One thing that constantly stems from the diary is this obsession with being there. Warhol would probably have been delighted that the following story found its place in this documentary about him, along with the photo evidence: “We went for Sean Lennon’s birthday… there were fans outside… I made a little heart candy box and a bracelet I made out of pennies… There was a kid there setting up the Apple computer that Sean had gotten as a present. I said that some man had been calling me a lot wanting to give me one. And then the kid looked up and said, «Yeah, that was me… I’m Steve Jobs.» And then he gave me a lesson on drawing with it… and I felt so old and out of it.”

Warhol’s greatest creation is Warhol himself. The Andy Warhol Diaries aims beyond the meticulously constructed persona – makeup, wigs, the robotic way of talking and self-proclaimed asexuality – by using valuable information from the diary. It’s an impressive deconstruction effort that combines this information with the critical interpretation of his artistic endeavors and the social and psychological contextualization of his work ethic. The obsession with (self-)covering and hiding, together with the fascination with icons (products and people, from Campbell’s Soup Cans to Marilyn Monroe and finally to Andy Warhol), are hermeneutically linked with the artist’s childhood. A son of Catholic immigrants from Slovakia, Warhol is impressed by church icons; raised in a working-class environment, he contextualizes on the canvas the American consumer culture that places the rich and the poor on an equal footing (Coke is Coke and it tastes the same for everybody, be it the President, Liz Taylor or the bum on the corner); impossible to pass as a straight man in a mainstream culture that shows aversion to homosexuality, Warhol hides behind exaggeration: he proclaims his asexuality, whereas his artistic creation indicates something else (from the first homoerotic nudes rejected by galleries to the films released in cinemas dedicated to gay pornography).

The most important aspect of the docuseries is precisely the artist’s romantic history; seen from an artistic angle, not an investigative one. The goal is not to settle the issue of Warhol’s sexuality (although it makes an important topic of academic debate, impossible to separate from his artistic creation), but to make the authentic voice and personal drama rise from the pages of the diary through all cultural artifacts, many of them created by Warhol himself. To humanize the robot, in other words: “Machines have fewer problems. I wish I was a machine, don’t you?,” says Warhol at one point. I’m not sure he would have fully supported such an endeavor, but he would certainly have appreciated the interest in it and especially the filmmakers’ creativity: the most important Warholian gimmick employed in this documentary is Warhol’s own voice, recreated through AI, who narrates his own diary. It’s an incredibly sad voice, longing for love, constantly concerned about artistic (i)relevance and fading away… it’s probably the most humane version of Warhol among all his portraits and self-portraits.

The Andy Warhol Diaries is available on Netflix.

Standing Up (Fanny Herrero, 2022)

“It takes a very long time to become famous overnight,” postulates at one point an agent about how one can break into the world of stand-up comedy. I hope that for Standing Up and its wonderful actors, this success will come much sooner. Even though it’s no masterpiece – thematically, narratively and stylistically speaking, the stakes are low – Standing Up is simply the light, easygoing series I so much needed: colorful, chic, dynamic, funny, upbeat, excellent soundtrack. Perfectly forgettable escapism, but well constructed, Standing Up is a bingeable series that I liked well enough to write about despite a tiny detail that I knew would give me a hard time: comic? comedian?… with or without “stand-up” attached?

This lexical confusion is also valid for the French stand-up scene (le stand-up, comique de scène or monologue comique), and it reflects the novelty of this genre, and also it’s borrowed nature. French culture has many well-established comedic traditions, but stand-up is not among them. And when the money supporting a show on the French stand-up scene is coming from Netflix, there is a chance you might get a diluted product. First, because you plug in to an imported subculture, thematically speaking (Netflix is full of American formats spoken in foreign languages), and second, because the platform itself often wants something back, something translatable and relevant for their primary market. Standing Up is so good precisely because it’s so French.

The show focuses on three Parisian comedians, three friends caught at different stages of success. Success, in this case, is inversely proportional to the amount of time you have to set aside for your day job, the one that provides the means to pay your bills.

Aïssatou (Mariama Gueye) has a stable job at a theater, but wanders the streets of the neighborhood with her little girl in her arms, emotionally blackmailing local businessmen to promote her stand-up show. She is well known enough to appear on posters, but she has to put them up on her own. She is quite popular in the industry, but she still does shows for small crowds. After her bit about stimulating your partner’s prostate goes viral, Aïssatou realizes that creative freedom comes at a price: the husband doesn’t want her to make jokes about their sex life anymore, the family nags her to use her success to tackle serious issues, and the agent suggests her not insist too much on the bit about racial discrimination, because people ultimately want to have a nice time.

Bling (Jean Siuen) is the oldest player in the field, the first and only one to make it big, but that was years ago. Even he has to work these days; he runs a family-owned Vietnamese restaurant with his sister, which they have redesigned into a comedy club. He connects more and more neurotically to the energy and humor of the younger generation he promotes, well aware that he has no new material prepared for his upcoming show. Now his hobbies include brand name sneakers and cocaine, he has stage fright and holds the belief that all the colleagues he has been promoting so far have become funnier than him. Bling’s act is mainly based on interacting with the public, that is, insult comedy. Pressured by his agent to show him new material, Bling goes on stage unprepared; a disaster that results in heckling and jostling.

Nezir (Younes Boucif) polishes his material in traffic while delivering takeout food. Sometimes his customers become the audience without knowing it: “Didn’t you order sushi? So, there you go, that doesn’t get cold.” In this line of work, you must always have a line or a comeback prepared (working the room/crowd), in every audience, there is always someone who thinks they’re funnier than you (a heckler), you have to feel the audience and know how to divert hostility (either make them laugh or make others laugh at them). Nezir is ready to quit the stage but instead, ends up mentoring Apolline, a student of good family, who has more than a few thoughts on the topic of little girls, sexuality and ponies… which she lets out in front of the microphone, to the horror of a mother whose favorite comedian is Molière.

There is an old saying in American stand-up that divides the stage into two: those who tell jokes (comics) and those who talk about things in a funny way and who have a well-defined style (comedians). Standing Up obviously focuses on the second category and manages somehow to capture the essence of this type of show. The comical aspect of the series has less to do with the jokes told on stage and more with the narrative device. In both cases, what counts more than the joke itself is the way it is delivered, the actors’ performance. It’s the anchor point around which everything else revolves: the protagonists’ great charisma (Elsa Guedj starring as Apolline is a revelation).

The quality of the material is obviously important but stand-up is first and foremost a performative art, and this French series manages to capture this aspect very well. Depending on how it is said, where it is said, and especially by whom it is said, the same joke will either fill the room with standing ovations or plunge it into awkward silence. Standing Up understands this dynamic very well, and its best parts are precisely those in which it explores this permanent negotiation between the one on stage and the audience.

Standing Up is available on Netflix.

Film critic and journalist, UNATC graduate. Andrei Sendrea wrote for LiterNet, Gândul, FILM and Film Menu, and worked as an editor on the "Ca-n Filme" TV Show. In his free time, he works on his collection of movie stills, which he organizes into idiosyncratic categories. At Films in Frame, he writes the Watercooler Wednesdays column - the monthly top of TV shows/series.