Hoping for the best. Nine films about sports

In Fotbal plus ai mei şi‐ai noştri (Football Plus Ours and Theirs), an anthology of football stories written in the ’90s by Radu Cosașu, the writer, film critic, and sports columnist who passed away a few weeks ago, he said that football is “a constant source of strength, the kind of strenghts that makes even the smartest person say, like a foolish child, ‘I’m dying of curiosity.’” Curious about trying this exercise of curiosity ourselves, we wanted to pay him a small tribute through a selection of films about sports – going for the king sport and not only.

Below, there is a 4-4-2 formation of some of the best examples – be it documentaries, feature films, or TV series – recommended by the Films in Frame team and contributors, that explore the fascinating and eventful world of sports.

***

The Witches of the Orient / Les Sorcières de l’Orient (dir. Julien Faraut, 2021)

A few minutes into Les Sorcières de l’Orient, a film about Japan’s unbeatable 1960s volleyball team, it was enough to confirm to me that Julien Faraut is one of the most profound contemporary filmmakers. Benefiting from his work at the French National Institute of Sport, where he was in charge of the 16mm archives, Faraut has built, in just a few feature films, an edifice capable of encompassing and extending the radical insights of a Franco-French tradition of thought which, from Eric Rohmer to Serge Daney, understood that sports is the ideal lab for studying the images of today and tomorrow. Les Sorcières de l’Orient is the opposite of that wonderful deconstructed portrait of tennis player John McEnroe, which Faraut made in his previous film, In the Realm of Perfection / L’empire de la perfection (2018): a hallucinatory juxtaposition of heterogeneous images, from animation to TV archives, turning the sports image into a kind of ground zero of audiovisual music – kinetics, ideal gesture, a flowing stream where everything flows infinitely. And perhaps never before has this limited idea of sports competition been closer to Eisenstein and his open montage towards the revolutionary harmony of the universe. (Victor Morozov)

***

Something Different / O něčem jiném (dir. Věra Chytilová, 1963)

Something Different – indeed, what a fitting title for the debut film of the iconic Věra Chytilová, appearing like a black star in the sky of a still-incipient New Czechoslovak Wave, already announcing its innovative intentions. This first feature directed by a woman in the history of Czech cinema is also an early example of a style of filmmaking that has become ubiquitous today: the hybrid, where fiction and documentary are placed on an equal footing, mutual discursive influences that serve the ultimate goal of revealing something of the reality beyond the screen.

I will focus rather on the documentary side of the film, in which we follow the intensive training of gymnast Eva Bosáková, who is preparing to participate in the last competition before her career retirement (the fictional side of the film explores the unsatisfactory life of a young woman, Vera, building a broader discourse on the condition of women in the ‘60s, torn between household chores and the burden of being a body). What a splendid shot is that in which Jaroslav Kučera’s camera spins simultaneously with the athlete’s body in the air – only the image can ever bring us close to the feeling of a professional athlete – a dynamic camera that often stops on the mirrors in the training room, both an aesthetic (emphasizing the plastic beauty of the body and the exercises it performs) and self-reflexive (in the end, it’s all about representation) artifice.

Of course, images of a pre-Comăneci gymnastic performance may seem somewhat naive to us, modern viewers, but how powerful are these shots capturing the training of an athlete at the end of her career, with the mistakes, repetitions, and abuses (with the coach’s screams and slaps, given with such a disturbing naturalness), containing all the force of a revolutionary act: breaking the ideological barrier of socialist realism towards a true understanding of the term “realism”. (Flavia Dima)

***

Eagles from Țaga (dir. Iulian Manuel Ghervas, Adina Popescu, 2022)

In Transylvania, in the village of Țaga, there is a football team where the coach and the players fight fiercely in every match, even though they are always at the bottom of the league table, in the fifth division.

The documentary follows Nelu Târnovan, the devoted coach who handles just about everything – from marking the touchlines to calling the players before the match to make sure there will be eleven of them on the field, so the game can take place, and last but not least, to training and encouraging them.

It’s a documentary that arouses curiosity, although the nature of the events presented is not that uncommon, as the captured atmosphere is not specific to a particular Romanian football team that happens to be very weak but can be found, in one form or another, in almost all domestic leagues. There is an unintentional humor, reminiscent of Creangă’s writings, that seeps in naturally, like a football player smoking a cigarette on the sideline or the reception committee greeting the team with shots of rakia.

When money and performance are rather out of the question, what remains is the passion and the desire to socialize that motivates players to find time, amidst parties, weddings, work, and other obligations, to also make it to the field and be part of teams that stubbornly persist, despite all difficulties. (Melissa Antonescu)

***

Diego Maradona (dir. Asif Kapadia, 2019)

Diego Maradona was so big that, after the news of his death, the owner of an auto parts shop in the suburbs of Bucharest wrote the message “Vamos Argentina! Vamos Diegoal!” on the shop’s billboard. There is something incredibly moving about this declaration of love, coming from a place thousands of miles away from Buenos Aires, for a superstar who captivated the entire planet. Made of archival footage and off-screen interviews, we witness the rise and fall of Diego Maradona, his heyday in Naples, where his exceptional career also came to an end. The result is a two-hour documentary that feels like four. Perhaps one of its merits lies precisely in that, in the fact that a film about Maradona could only be a film of contradictions and which manages, at the same time, to evoke the deepest melancholy. (Anca Vancu)

*

There is an English term that can equally work as a definition for cinema, but also for well-played football: poetry in motion. It is clear that no one played football like Maradona did. And in the wake of Asif Kapadia’s documentary, made almost entirely of archive footage, what remains are not the various scandals and gossip, with their seductive patina of 80s tapes. What remains is just magnificent poetry.

In any case, the year after this film came out, Diego died. Since then, Argentina has won the World Cup, and Naples has claimed another scudetto. As the saying goes: God is up there watching. (Codrin Vasile)

***

Senna (dir. Asif Kapadia, 2010)

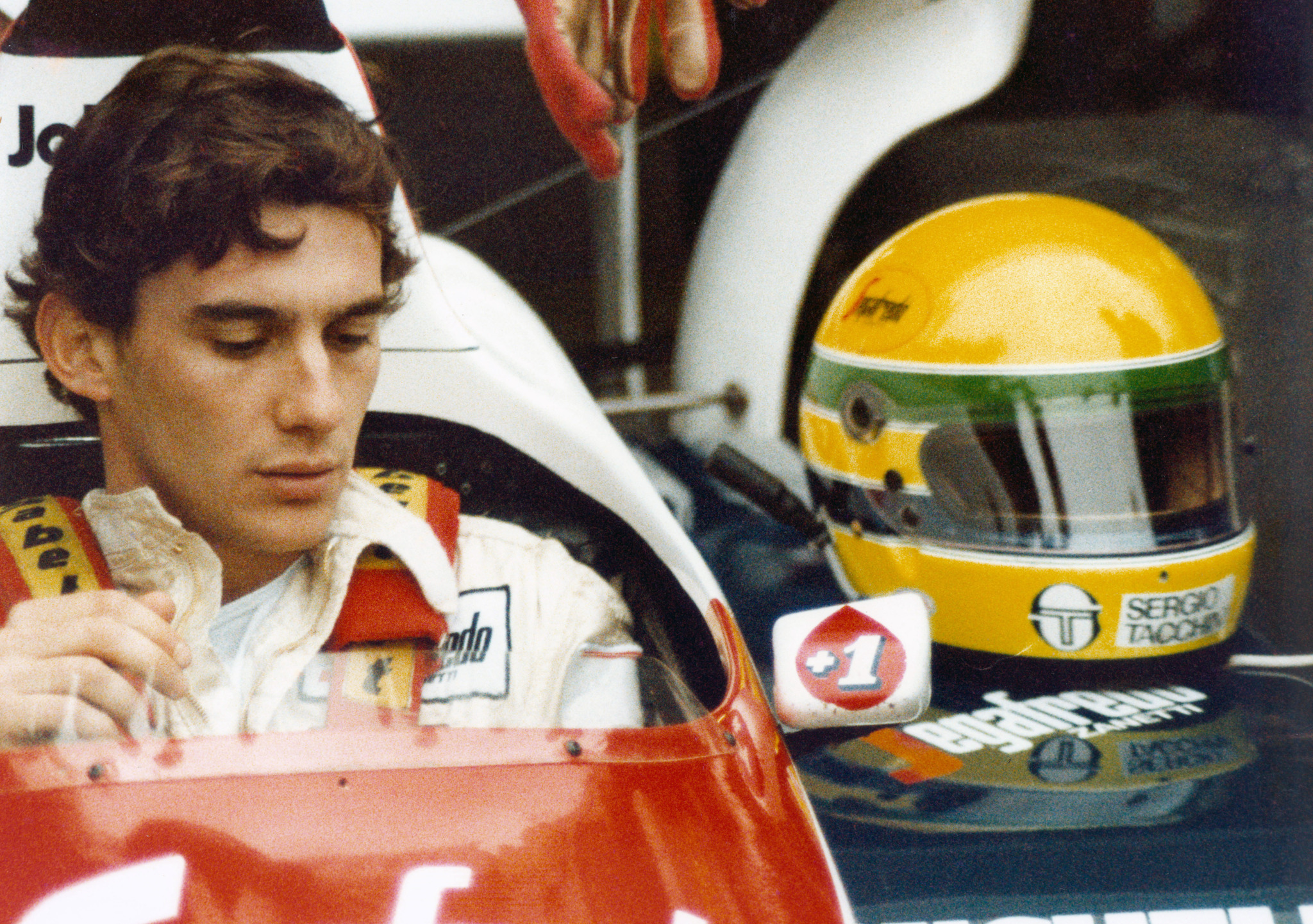

The death of Ayrton Senna, who crashed into a concrete retaining wall on May 1, 1994, on the Imola Circuit during the San Marino Grand Prix, stirred up waves of emotion across the world, from his native Brazil to the streets of Romania, where the kids of those times recalled, in shock, the moment of impact. In a sport of elites and split-second timing, drowned in dizzying budgets and marketing, the rebellious child of Formula One, one of the last dreamers, had been greatly loved, an adoration to match his ambition.

Senna, Asif Kapadia’s 2010 documentary, especially in its nearly 3-hour extended version, has the great merit of avoiding many of the pitfalls of hagiography that “authorized” biographies usually devolve into. It also has the advantage that its subject, larger than life and legendary for its impossible charm, is already a romantic figure. And his rivalry with Alain Prost, one of the greatest in the history of sports (from which the latter comes out a bit ruffled, in his role as a cerebral opponent, but somewhat petty and lacking charisma), is an opportunity for Kapadia to build, from archival footage of some extremely intense races, a rollercoaster of emotions that culminates in one of the most poignant endings in cinema. (Dragoș Marin)

***

O.J.: Made in America (dir. Ezra Edelman, 2016)

The ESPN miniseries takes a fascinating and generous dive into the recent history of the United States, starting from a particular case, the rise and fall of the famous American football player O.J. Simpson. Director Ezra Edelman builds around his story a cultural and political retrospective on the segregation and systemic racism pervading the country, showing how American society could be manipulated and divided in the 1990s by the media and the first live broadcasts of what was called the “trial of the century”.

We follow not only Simpson’s winding journey – a young man of color who rose from a disadvantaged neighbourhood to become a marketing prince – but also the great scandals and changes that have always followed a society obsessed with sensationalism and a certain cult for heroic figures. And this trajectory proves to be a multi-layered eccentric tale, skillfully assembled like a lasagna in which the chef adds surprise after surprise. Given that it manages to be both a cultural and historical study, one that can be revisited to understand the great upheavals of American society between 1950-2010, O.J.: Made in America can be considered the most relevant audiovisual production ever made on a sports theme. (Ion Indolean)

***

The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (dir. Tony Richardson, 1962)

If there’s one thing that runs like a red thread through the whole of British cinema, it’s sports – present as the football games played on the streets of the working-class neighbourhoods in British social realist films, as well as the horse-riding scenes in period dramas. Sports separate classes and, within them, unite the people. But more precisely, sports go hand in hand with the British coming-of-age – it’s the place of small territorial battles among students, the site of rebellion, but also of abuses and outbursts of the young generations who are constantly under pressure.

While it may appear in the title, to say that Tony Richardson’s masterpiece, The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner, is a film about sports risks missing its essence. The athletic performance of a young man in a reform school serves as a pretext for a discussion about the system and privileges, compromises, and autonomy. The metaphor of an individual sport as a double for a solitary existence may not be the most ingenious, but the drama of a destiny where it seems like everyone has abandoned you is extremely poignant. The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner is also a unique stylistic exercise, not only because it reflects the pioneering work of the British New Wave but also because it exploits something whose “why” I’ve never been able to fully grasp: long-distance running is one of the most cinematic sports out there. (Teodora Leu)

***

The Second Game (2014) & Infinite Football (2018), dir. Corneliu Porumboiu

Probably no Romanian filmmaker has taken sports as seriously as Corneliu Porumboiu did in his documentaries The Second Game and Infinite Football. Of course, “seriously” in the sense that he dedicates to football – both in its conventional form and in an experimental exploration – two films that feature someone close to the director. In The Second Game, it’s the renowned former referee Adrian Porumboiu, the filmmaker’s father, and in Infinite Football, it’s a childhood friend, Laurențiu Ginghină, a civil servant at the Vaslui Prefecture who claims to have some revolutionary ideas for changing the rules of football.

The documentaries are lighthearted, taking on a playful tone, with some melancholic notes. Both films are only tangentially about football. For Corneliu Porumboiu, this sport becomes a pretext. On one hand, to encourage his father to reminisce about a bygone era (the end of the communist period) through the lens of a Steaua-Dinamo derby played in the winter of 1988, which he refereed. On the other hand, it allows him to once again explore (as he had done in all his previous films) the relationship between norms and their questioning or even subversion. Both results are admirable – two of the most inventive and original Romanian non-fiction films post-2000. (Ionuț Mareș)

An article written by the magazine's team