Tour de France: Unchained – Cycling without Cycling

The multicolored caravan that is the Tour de France makes an eight-episode-long detour through the well-worn paths of Netflix. This is an opportunity for the chronicler to check, all across the notes in his viewing diary, the state of the relationship between cycling and cinema, these two all-consuming passions that have seen the light of day almost simultaneously, back when the world was still a romantic place.

Episode 1

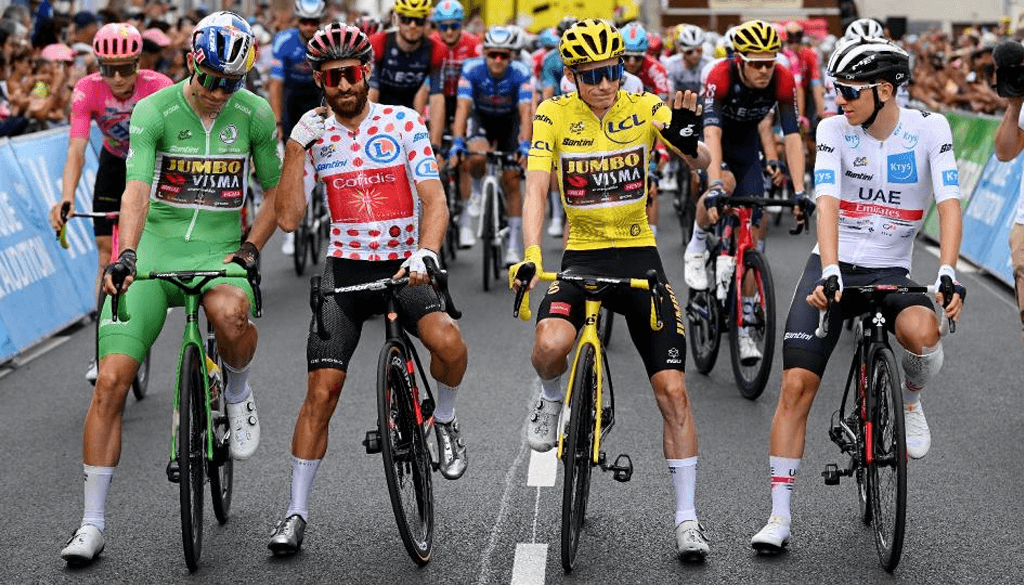

The racers haven’t even yet started pedaling, and I’m already wondering: what am I doing here? It’s enough to take a look at the first images – cyclists advancing in slow motion towards an awards stage, accompanied by bombastic music – for me to have the compulsive desire to turn this thing off. Barely a minute has passed and it’s already pretty clear where this miniseries made by the creators of F1: Drive to Survive is heading. To be fair, maybe this lazy type of imagery, done in the vein of Top Gun, might be fit for a sport like Formula 1, which is much more focused on individuality, but it’s completely disconnected from cyclism, which is first and foremost an adventure, an odyssey. Then and only then, it’s a one-on-one rivalry.

I persevere. The episode presents us with the struggle of a cyclist specialized in counter time to win the opening lap of the Tour: a counter time on the streets of Copenhagen. The showrunners give us a few shots of the cyclist training in an air tunnel in England, whereas an intertitle promptly announces that it’s “three months before the start”. Then, during the race, the cyclist falls twice, because the road was wet from the rain: this is the entirety of his narrative arc.

The episode then goes on to trail The Yellow Shirt, the surprise winner of the lap. The final focuses on his task of leading his agile teammate to victory (the latter confesses that he loves to win and Hayes to lose). But the man gets stuck in a collective fall, then is brought back to the platoon with great efforts, just in the nick of time for him to release his winning sprinter: another narrative arc. I finish the episode and then I turn the screen off. It’s too much already.

Episode 2

Episode 2 is titled “Welcome to Hell!”, after the “Hell of the North”, the legendary cobbled roads of northern France, on which the Paris-Roubaix one-day race takes place every year, which the series never even mentions. And this is because the series doesn’t care much about history – I’d even go as far as to say that it doesn’t care much about cycling, either. Like any good industrial product, it’s concerned with stars – and stars, as we know from the Golden Age of Hollywood, don’t actually work, and don’t actually have a proper object to work with, so they simply just exist, and that is already more than enough. After we visit the home of Wout van Aert and see him taking his son’s potty out of the trunk of his car, I start to get the mechanism: this unchained Tour de France allows itself to not intervene in terms of cycling (in this case, thank goodness, the images on the television speak for themselves), instead compensating with a hell of an ordeal – that of turning some poor athletes who are just asking for peace and quiet into true, autonomous cinema starts.

The trouble is that a cycling platoon is made up of around two hundred souls. Of course, there are starts within their midst, but to wish to only focus on them is, no matter how you look at it, a means of falsifying the greater picture. Moreover, it means reproducing a hierarchy that cycling – with its ultra-complex classification system – constantly frustrates and renegotiates. It is precisely this tension between the individual and the collective that underpins the sport’s greatness, a tension that the series has no idea how to translate into dramatic terms.

Episode 3

This is where I feel that things are starting to get more interesting. The episode, painfully translated as “The weight of a nation” (Le Poids d’une nation), is about France and the local audiences’ relationship with their teams and idols. Two such teams are presented: Groupama-FDJ, which charismatic manager Marc Madiot describes as the Frenchest of those gathered at the starting line, and AG2R-Citroën, which Julien Jurdie cheesily describes as the French team that has gained the best results in the past two decades. As such, the series imagines a rivalry between these two teams. And so, there is no way for it to even whisper to us that there are at least three more French teams at the starting line, whose sole misfortune is not having signed a contract with Netflix. We go to the farm of Thibaut Pinot, a road rider for Groupama-FDJ, who is preparing for his favorite climb (he’s going to lose), and witness the victory of Luxembourg’s Bob Jungels (AG2R-Citroën), who beats the same Pinot at another stage. The “creators” have a stroke of dumb luck.

Episodul 4

I keep thinking of Bob Jungels, the way he starts his presentation, just like everyone else, with “My name is Bob Jungels and I compete for the AG2R-Citroën team”. It’s just that Jungels no longer competes for them. The strange temporality of a series that is nothing more than a recap of a sporting event that is nothing more than pure ephemeral matter. Things destined to die at dusk, are replaced the next day by more feats, that only linger in the minds of a select few, the most precious keepers of collective memory. What is the purpose of seeing these things now, when a new Tour de France (one that is even more interesting) has invaded our television sets, and the happenings of last year are no longer of interest to anyone – and that’s a very good thing since that’s how sports work: they’re destined to never be definitive, instead, they’re always ready to start once more from zero, over and over again.

One could say that the show started on the 8th of June, and was meant to act as a trailer of sorts to the 2023 Tour. And that, anyways, it’s an offering for the uninitiated, those who have no idea what the yellow shirt is, or what the stages of a sprint even are. However, I do wonder how many such cinephiles actually hurried to discover this year’s platoon after running into this series. How many of them wished to move from Formula 1 to cyclism. In my opinion, Tour de France: Unchained lands on a sterile fault line: it’s too dense and confusing for newcomers, and too full of clichés and stale information for fans.

Episodul 5

Episode 5 is about the victory of young Tom Pidcock – one of the super-talents of the new generation – on the legendary Alpe d’Huez climb, on France’s national day. Pidcock’s downright incendiary skills – the almost maniacal way he turns at over 100 kilometers an hour – would be enough to steal the show and offer a lesson on the art of being a sportsman. But no. “The creators” feel that, to keep their audience focused, the simple gesture, ideal and perfect, of the athlete is not enough. So they cobble up a story by using whatever is on hand: another cyclist, equally young and eager to assert himself (one can feel the showrunners praying at the altar of rounded narratives) joins him on the day’s lap. It doesn’t even matter that three more people are coming along with him, all of them just as capable of scoring the victory: their issue is not having signed a contract with Netflix! It’s not like they’re erased in Photoshop, but to be honest, it’s not that far off, either: this imaginary rivalry is all that they need to drag the episode toward the finish line.

Episodul 6

My suspicion that “the creators” have not spent one single hour of their lives in the saddle is confirmed – or, if they did, they were too busy reading notifications about their previous hit, the F1 flick. Why else would someone brush off all of the inexhaustible and irreducible reasons for riding a bicycle – the desire to overcome one’s own limits, the search for oneself – in favor of a triad (suffering, sacrifice, scandal) whose sole rationale is to sell things? Van Aert has all the right to be outraged at the outcome, a firecracker that seeks out the grating, the sensational, the gurgling emotion – which, on top of it all, is also grossly oversimplifying. Because cycling and mainstream cinema only overlap up to a certain point, and they certainly cannot be reduced to these mano-a-mano fights that are designed at the editing table, thanks to a retrospective gaze that is capable of tracing all-too-convenient red lines, so that it may draw out the sizzle.

The maneuver might have succeeded, after all, if Netflix had the agreement of all the teams – but it only had a deal with seven out of 22! Add this to the fact that UAE Team Emirates, the double winner of the Tadej Pogacar Tour, is missing! And so, “the creators” are also stuck with the impossible mission of turning the Slovenian from the champion of the masses – with his disconnected and bemused demeanor, it wasn’t all that hard for him to become popular – into a hungry ogre, the all-too-perfect antagonist of this miniseries in search of cheap Manichaeism. At one point, he is shot in slow-motion while drinking water from his bottle, seeming more terrifying than the Joker himself. His only shortcoming? The fact that he didn’t get a bill from Netflix, of course!

Episode 7

Another rivalry created in the same mold of primary affect: that between David Gaudu (young, French) and Geraint Thomas (old, British): spot on! Everything in this show is either an absolute contrast or an uncanny similarity, forced association, or concocted difference: no nuance could ruin this masterclass in cinema’s most rudimentary tricks. I’m tired.

Episode 8

Eureka! The first (and only) cinematic shot in this series springs forth along with Jasper Philipsen’s victorious sprint on the last leg of the Champs-Elysees: we see him shot on a camera that advances in parallel with him, hundreds of meters in one fell, slightly buzzy, yet inherently spectacular swoop. This is an antidote of sorts to all of this rabid thirst for visuality that Tour de France: Unchained, with its annoying insistence on behind-the-scenes drama and key moments in the race, to the detriment of cycling’s trademark dreamlike duration, has constantly encouraged.

I rush to turn on the television in hopes that I will see a portion of the field race: meaning, a few hours replete with aimless images, where the colored line of cyclists slowly crosses through a landscape capable of helping me relearn the craft of patience. And so I recall this quote belonging to Pierre Chany, the great cycling chronicler of L’Équipe, by now almost a half-century old, which rings even more authentic and painful than it ever did: “The heart shrinks.”

Title

Tour de France: Unchained

Film critic and journalist; writes regularly for Dilema Veche and Scena9. Doing a MA film theory programme in Paris.