Interview about a film that does(n’t) exist: Fabrice Aragno, on Jean-Luc Godard’s Drôles de Guerres

His mind was like a tree – a forest of thinking. His thoughts were arborescent

As soon as I turn on my recorder Fabrice Aragno stands up to check the windows of the Viennale interview office, on the ninth floor of the Intercontinental Hotel.

“There’s wind. I’ll just close the window for the sound.”

A few moments later, he changes his mind: “In fact, you’re not using the recording for the sound. But do you prefer to have the background noise – to remember Vienna?” He then reopens the window: “Well, it’s just a buzz.”

There is something about this gesture of his that completely floors me – so natural that it almost seems to be a reflex, signaling a formidable speed of thought and reaction, coupled with the deeply poetic and touching idea of contemplating future memories. It’s a sample of artistic awareness and cinematic thinking in real-time, applied to a detail so minute that most might even consider it negligible, transforming it into a point of connection.

The reason we are seeing each other this morning is the last film completed during Jean-Luc Godard’s lifetime, Film annonce du film qui n’existera jamais: “Drôles de Guerres” (or, in translation: Trailer of the Film That Will Never Exist: “Phony Wars”; hereafter Drôles de Guerres). Just twenty minutes long, this short film was screened at the Cannes Film Festival eight months after Godard opted for assisted suicide on the 13th of September 2022 at his home in Rolle, Switzerland (where he had spent the second half of his life with his creative and personal partner, Anne-Marie Miéville).

I’m describing something that I still find very hard to comprehend, or accept: Godard is dead. I’m resorting to this highly descriptive and plastic language because of this, and perhaps also due to the lack of confidence in my ability to write something revelatory (or that doesn’t sound clichéd) about one of the most written-about filmmakers in the history of cinema. Its Vitruvian Man, he forever changed the face, history, and trajectory of film: more than just a revolutionary filmmaker (in every conceivable sense of the term) and an encyclopedic cinephile (the only one to ever come close being Harun Farocki), but indeed an expansive and indefatigable intellectual, inhabiting the innermost layers of film language to destroy it from the inside out.

Fabrice Aragno was Jean-Luc Godard’s closest collaborator for the last two decades of his life. It started with Godard’s 2004 feature, Notre musique (which, coincidentally, is briefly reprised in Drôles de Guerres), a few years after the Swiss filmmaker finished his studies at the prestigious ECAL art school in Lausanne. In their two decades of collaboration, Aragno has done everything from production work to cinematography, editing, sound design, and mixing – and has been the driving force behind some of the most spectacular artifices and technical solutions in Godard’s late cinema, like the breathtaking 3D scenes in 2014’s Adieu au Language. He is also a director in his own right (his latest short film, Parenthese, a poetic observational documentary about the first lockdown, screened at the 2021 edition of Visions du Réel) – and is part of the Casa Azul film production collective, which is based in Switzerland.

It’s hard for me to talk about Godard in just ten minutes, because he was twenty years of my life.

Drôles de Guerres is the first posthumous Jean-Luc Godard film to come out, and the final film on which he worked during his lifetime, wrapping it up around six months before his death – it’s hard not to see it as a testament of sorts. Composed from a series of still frames culled from a notebook (handwritten by Godard), segments from his 2004 feature film Notre musique, pieces by Shostakovich, and a candid fragment of his own voice, Drôles… had its international premiere at Cannes, screening alongside the latest short film of Portuguese maverick Pedro Costa, The Daughters of Fire. It’s a pairing that many festivals have reprised – including the Viennale, which added Michael Snow’s seminal Wavelength to the mix.

Aragno tells me that he enjoys the fact that the films are traveling together, even though their formal proposals are quite different: “[Their first screening together] was just wonderful. There were five minutes of silence and darkness in between them, which was a proposal of Thierry Fremaux. It was simply wonderful.” The same cannot be said of the other pairing made with the film on the Croisette, together with Florence Platarets’ very disappointing biographical documentary, Godard par Godard – which he describes as “shit”.

“You have to stop me sometimes,” he warns at one point. “It’s hard for me to talk about Godard in just ten minutes, because he was twenty years of my life.” Throughout the entire talk, he consistently uses the present tense to talk about him as if he were still amongst us – pointing out that even after decades of collaboration, they still used polite pronouns to address each other, which he regards as a gesture of affection.

I ask Fabrice about the film’s very particular model of production and formality – in previous interviews, he had mentioned that Godard had left a series of extremely precise indications (down to the exact duration of certain shots, timecodes, and all) regarding the way that it was supposed to be assembled, both in terms of image and sound. Was the film always going to look the way that it does now, especially considering its title?

“No, it’s always a process. It’s always like that with Jean-Luc Godard,” Aragno says. At first, Drôles de Guerres was thought out as a feature film – that was going to have the backing of Yves Saint Laurent. “They wanted to produce a film made by a big auteur, meaning that they just wanted to take the name of Godard and glue it onto themselves, like ooh, look at what we’re making”, he quips. Godard saw this as an opportunity to adapt Charles Plisnier’s Faux passeports (Memoirs of a Secret Revolutionary, 1937), a novel that follows several disillusioned characters in the aftermath of the 1917 Revolution, what Aragno calls “the beginning of communism” – and the different ways that the urban bourgeoisie, the intellectuals, and proletariat experienced this moment in history.

“Well, when you understand Godard, you know that him making an adaptation is… much rather a pretext, an initial idea,” he adds. The twist was that the director was considering returning to shooting on film stock (across all formats – color in Super8 and 16mm, black-and-white in 35mm), because “his first idea was to do a film the way he did before, but with his current way of working” – however, shortly after a series of technical tests, the pandemic struck, bringing the entire project to a halt.

“It took time. It took everything. And it gave a certain loneliness,” Aragno says. “An obligation to be alone.” It wasn’t necessarily a problem for Godard that the world had come to a stop. “For him, it was ok that everything stopped, it’s a pretext to do nothing”, he says. But at the same time, it frustrated his efforts to get Drôles de Guerre off the ground – and attempts to restart the project with the help of Aragno and close collaborator Jean-Paul Battaggia (who was in charge of keeping in contact with the producers) were very difficult. Aragno had already managed to find film stock and various other materials to prepare for tests, to give Godard “some things to do, to provoke him – like a tennis player, launching the ball and waiting for him to send it back”, but the successive waves of the pandemic obfuscated any progress they managed to make, compounded by the ninety-year-old Godard’s increasingly frail health.

Jean-Luc needed to work for a living. He was not rich at all.

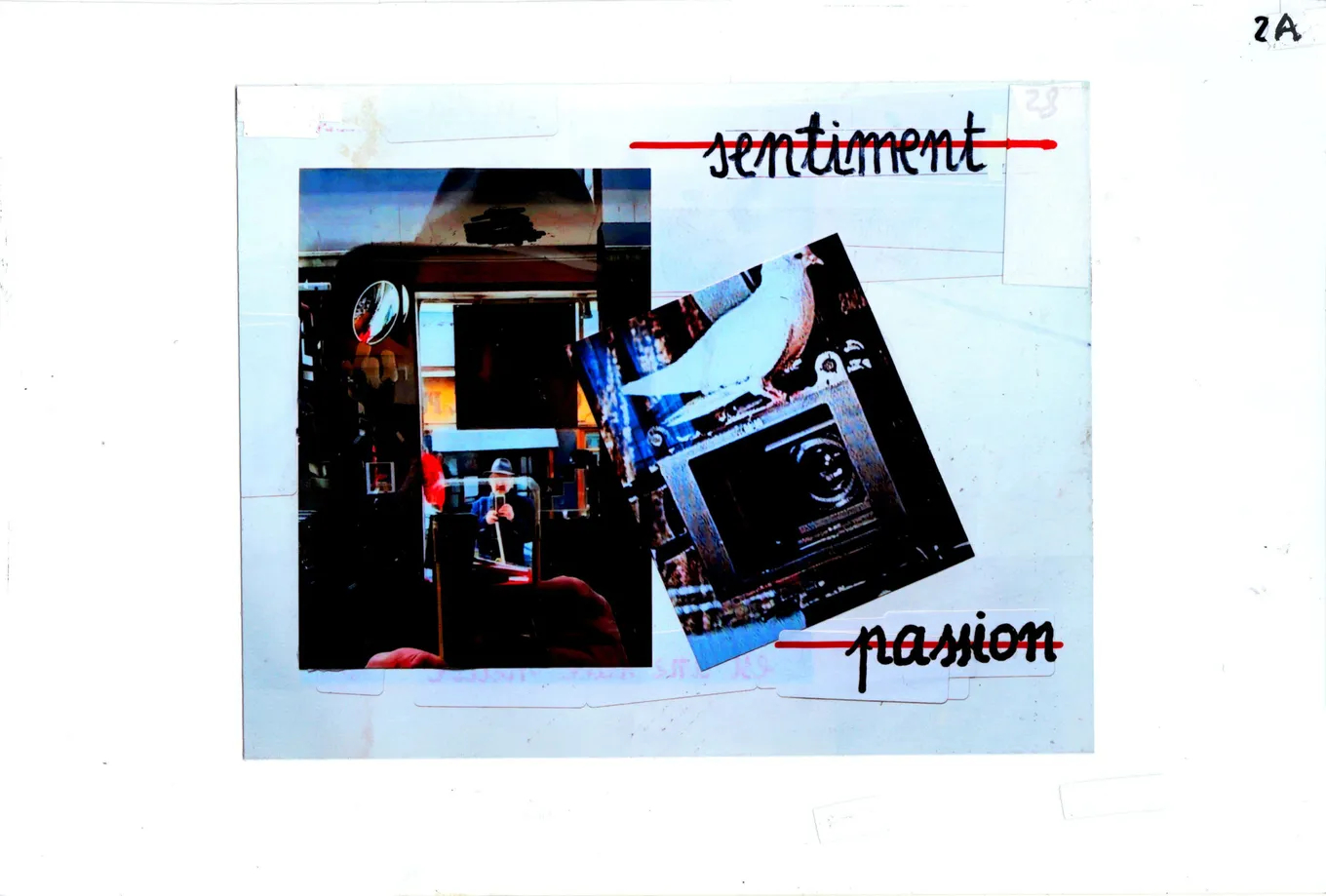

Ultimately, it became impossible to shoot the film. “I think that Covid was a good pretext for him – and it was what made the film appear in the way that it does,” Aragno says. Still, his creativity was undeterred, and he started putting his ideas about the film to paper in a notebook, filling it with words, drawings, and collages of images: “His mind was like a tree – a forest of thinking. His thoughts were arborescent,” he adds, his eyes lively, spreading his arms as if to circumscribe a large, green crown, and a network of branches. “He needed to freeze things, to clear his mind a little bit and put things to paper” – especially since Drôles de Guerre was not the only film that he had in mind, at the time. The other film that he was working on at the time, titled Scénario, is still in production – along with several other projects that Aragno intends to finish, based on indications left behind by Godard.

The result of this process is what Aragno calls “the scenario du scenario, the script of the script”: a brochure of sorts that acted as an outline of the project, which had the advantage of “already [being] edited because it’s a piece of text and images”. However, this being Jean-Luc Godard, the result is an abstract work of art typical of his late period, which freely combines words and various species of images into the body of a single piece. During a meeting at Godard’s office in Rolle, they decided to turn this 60-page-long A5 notebook into a film in its own right – which would also fulfill his obligations with the project’s backers, since “the contract was for a film, not for a piece of paper”.

“One thing you should know is that economically, Jean-Luc needed to work for a living,” he says. “He was not rich at all – even though people maybe thought that someone like Godard is very rich. No, he wasn’t. Due to his way of making things, he always had to sell or give the rights to his films away.” On the other hand, this also determined his very prolific manner of working: “Once a film was finished, he gave it away and went on to the next one. He never kept them – always returning to a clean slate and then re-creating things every time. And because of this, it was a never-ending creative process, from the early beginning to the very end, he never redid the same thing.”

Aragno recalls that Godard took some post-its and started writing down the duration of each individual still frame from the notebook, which amounted to a set of assembly instructions: “This one is seven seconds, this one is ten seconds, this is five…”. Initially, they came down to a total of six minutes, which they considered to be much too short – so Godard suggested multiplying each duration by five. After scanning the book, Fabrice started editing the footage on his laptop one morning, in his kitchen – even though he has his studio – per Godard’s instructions.

Of course, he had no way of really knowing how things were going to work out before pressing play on this assemblage, which, at the time, was silent. Aragno describes the first time he watched the initial edit of Drôles de Guerre as a revelatory moment – as if he were witnessing an idea come to life in real-time, in front of his own eyes, which Godard had all planned out without even seeing it himself. “If you focus on the images, you begin to think. After ten seconds, it’s frustrating, because you already know everything that is in the image. But after that, you begin to think, you start having an abstract idea – and then, suddenly, another page, another image arrives. And that’s pure cinema. It’s total cinema,” he says. “This creates a third image. It’s something very simple, but so fundamental in cinema. And this film is about that, completely – this third image that does and doesn’t exist.”

Two days later, Godard sent him his feedback – he pulls out his phone and shows me an email: a timeline of the entire film, written by hand. “For example, here it says: «At minute four, you take a fragment from Notre musique that starts at minute 57, and let it run for three minutes. Then, at minute eleven, you take three minutes from a discussion that we recorded in December. Then, from minute fifteen onward, another part of Notre musique», and so on”. A re-usage and re-conjugation of an already-extant image – which “freed me from a part of the work [as a cinematographer]“, Aragno jokes. “And Jean-Luc was also a procrastinateur.”

Like the old masters, watching the same painting every day, all day long

One of his final indications concerned the music. He pulls out an email dated January 8, 2022. “Between minutes 7 and 11, add two minutes of music. Use whatever you’d want as music. Ce que vous voulez comme musique,” he reads. Even though he tried to guess his preferences, Godard kept on insisting that he should choose whatever he liked. “I said, Okay, Jean-Luc. I know I couldn’t put something like Vivaldi’s Four Seasons. [laughs] And so I began to look through all of the music that I have, all the DVDs and CDs that I have in the studio (I didn’t want to use websites), looking for a Russian composer, because the main theme [in the film] was the Revolution of 1917.” After considering the works of Stravinsky and Prokofiev (“too orchestral”) or Schnitke (“too contemporary”), he settled on a quartet by Shostakovich – whose works had been suppressed during the reign of Joseph Stalin, which, in his eyes, created a direct connection to the Plisnier’s novel.

Finally, they met again at the beginning of March, after Godard had watched the final edit – and Aragno, incredibly, takes out his phone and plays a recording of their meeting. The gesture completely disarms me; I immediately feel emotionally overwhelmed. The old maestro’s raspy, slow, considered tone pours out of the speakers of his iPhone: “I think it’s better like this, to arrive at twenty minutes [of duration]. For me, it’s like paintings. When you visit a museum, when you watch the tourists looking at the works of art, it’s rare for you to stay for just two seconds in front of a painting. You remain in front of it. Or like the old masters who watched the same painting every day, all day long.” I’m completely stunned. Fabrice scrolls to another part of the recording. “I don’t know what you thought when I told you that this is one of my best films. I like the fact that it’s very long. Very silent. Thus, it’s perfection.”

“Sorry, I’m a bit speechless”, I tell him when the recording stops. “No, no problem.” He looks the other way. “Pauvre Jean-Luc,” he says, almost in a whisper to himself.

When I manage to recollect myself, I ask him whether the film’s perfection also lies in its unfinishedness. “It creates a place for you. A silence for your silence. Or for the silence of the cinema. All the living people, moving, coughing, all the life that is inside of it. The silence of the film lets life be – our life, not the life on the screen. Our life, our presence.”

Although the maverick nature of Godard makes all of this sound incredibly plausible, I listen to the story of how the film was assembled with a degree of incredulity. It’s almost shocking to imagine that one of the most important filmmakers in the history of cinema had purified his praxis to such an incredible extent that he reached a point where he could completely visualize a film of his within his imagination, and is not even the first person to see his film – along with the fact that its necessities were so modest that they could be assembled at home, by relegating a large amount of control to collaborators. This extreme artisanal nature, this particular kind of simplicity of means is indeed deceptive at first look – because only a true master of the craft would be capable of such a large degree of both abstraction and precision.

He didn’t take my freedom away. He let things be. And he was like that with everyone.

Aragno’s description of a third image strikes me – I tell him that, when I watched the film for the first time, I quickly abandoned taking “regular” notes and started writing down the abstract thoughts that the film was generating within me. And that I felt like this about much of Godard’s late cinema – that it gives spectators such incredible autonomy of thought, complete freedom to create networks of meanings, pushing you into constant dialogue. So I ask Aragno about how he relates to Godard’s later approach to cinema authorship – which stands in stark contrast to the archetypal image of the filmmaker as an autocratic figure that exerts absolute control over what happens within the image, on the set, and in the editing room. After all, this was not the first time that he’d been given a lot of freedom in his collaboration with Godard: I mention the anecdote of Film Socialisme (2010) when the director canceled his plans to attend a shooting onboard of the Costa Concordia cruise ship and simply instructed Aragno to film whatever he wanted.

“It’s nice that you mentioned Film Socialisme,” he says. “He didn’t give me freedom, in fact. He didn’t take my freedom away. Which is not the same thing. He let things be. And he was like that with everyone.” He compares the process to the act of picking up a flower: “If you do that, you kill it. Instead, he would just film the flower, together with the wind that was blowing over it.” He adds that even though he was the one who shot the images, in the end, they became Godard’s.

As we near the conclusion of the interview, I ask him how he regards the landscape of contemporary cinema – and even though I don’t mention Godard’s passing (after all, his death was regarded by many as a parallel to the “death” of contemporary cinema), Aragno’s thoughts naturally drift towards that direction. “I’m a little bit… like a dead leaf [une feuille morte]. I was on that big tree with him, protected by the freedom of thinking, making… All possibilities were open. And now, okay, we can still continue [working], but the tree is not there anymore. It’s a little like being in a desert.”

He mentions that many directors (like Jean-Marie Straub) who have recently passed away were like “protectors of another way of making film – because film is not only about having a story to tell, it’s also about having something to express. It’s a way of expression, not one of telling. It’s stupid to use cinema just for telling. You can tell things in books, you don’t need a cinema for that. It’s very sad.” He also brings up the global rise of the far-right, of dictatorships and wars – “We’re just going… I don’t know. I’m a feuille morte, very much trying still to be alive and trying to do my own stuff, but it’s hard to be alone.”

We’ve been discussing for over an hour, and our time is slowly running out. And, as much as I share many of his fears regarding the current state of cinema, of the world, heck, even of loneliness – still, I try to think of a way to bring the discussion to a more luminous conclusion. “You said that Godard’s mind was like a tree,” I ask. “Have you ever thought about what kind of tree it would’ve been?”

Fabrice ponders the question for a few moments. Switching to French, he says: “It’s an immense tree. Immense.” He can’t think of a specific type or species of tree, just the fact that it’s a really big one, even though Godard was a rather petite man – and that the shelves in his studio felt branches, and that you could just jump from one to another. “Once you arrive there, in his studio, you get the feeling of being on his shoulder, and that his shoulder was like a branch.”

“I don’t know, it’s the image I have,” he continues. “If I had to imagine Jean-Luc, he’s like a huge tree. Something like a palm tree, or a baobab. And there are apples, lots of fruits everywhere. There are lots of ideas, and lots of possibilities. There is wind.” He remembers that they used to go out on long, silent walks with their dogs – and that on one occasion, as they sat down after an hours-long period of silence, Godard said something beautiful – paraphrasing Pierre Garnier – that “birds are the words that trees exchange. And when Jean-Luc tells you that, then, well…”.

We both take the elevator downstairs – I have to go to a screening, and Fabrice is going another way. As we say our goodbyes (an occasion by which I attempt to make a joke about my slightly ridiculous choice of clothing that day: a striped sweater emblazoned with a dancing Snoopy), Fabrice makes one last remark; which has stuck to my mind ever since:

“You know, I still believe in Snoopy.”

Title

Film annonce du film qui n'existera jamais: “Drôles de Guerres”

Director/ Screenwriter

Jean-Luc Godard

Year

2023

Film critic & journalist. Collaborates with local and international outlets, programs a short film festival - BIEFF, does occasional moderating gigs and is working on a PhD thesis about home movies. At Films in Frame, she writes the monthly editorial - The State of Cinema and is the magazine's main festival reporter.