KVIFF: C’est pas moi – Carax, after Godard, and Godard after Carax

When you’re a French director

You’re an auteur as well

What does that mean?

Every scene must be obscure as hell (as hell)

– Sparks feat. Leos Carax: “When You’re a French Director”

It’s quite telling that, in addition to Steven Soderbergh’s Mr. Kneff, my second favourite thing from this year’s Karlovy Vary is also a video-essay of sorts – telling if not for the shift in contemporary film landscape towards post-cinema and essay form, then at least for my personal preferences.

The title of Leos Carax’s latest effort, which is only 41-minute long, is nothing but a Magritte statement: C’est pas moi / It’s Not Me, where the film takes the shape of a curious self-portrait, inflated, self-ironic, and unexpectedly vulnerable. Carax’s endeavour, sublimely balancing between film theory and a mid-career crisis (as it marks 40 years since the premiere of Boy Meets Girl), seems to stem from a question posed to him by the Centre Pompidou for an exhibition that never happened: “Where are you now, Leos Carax?”

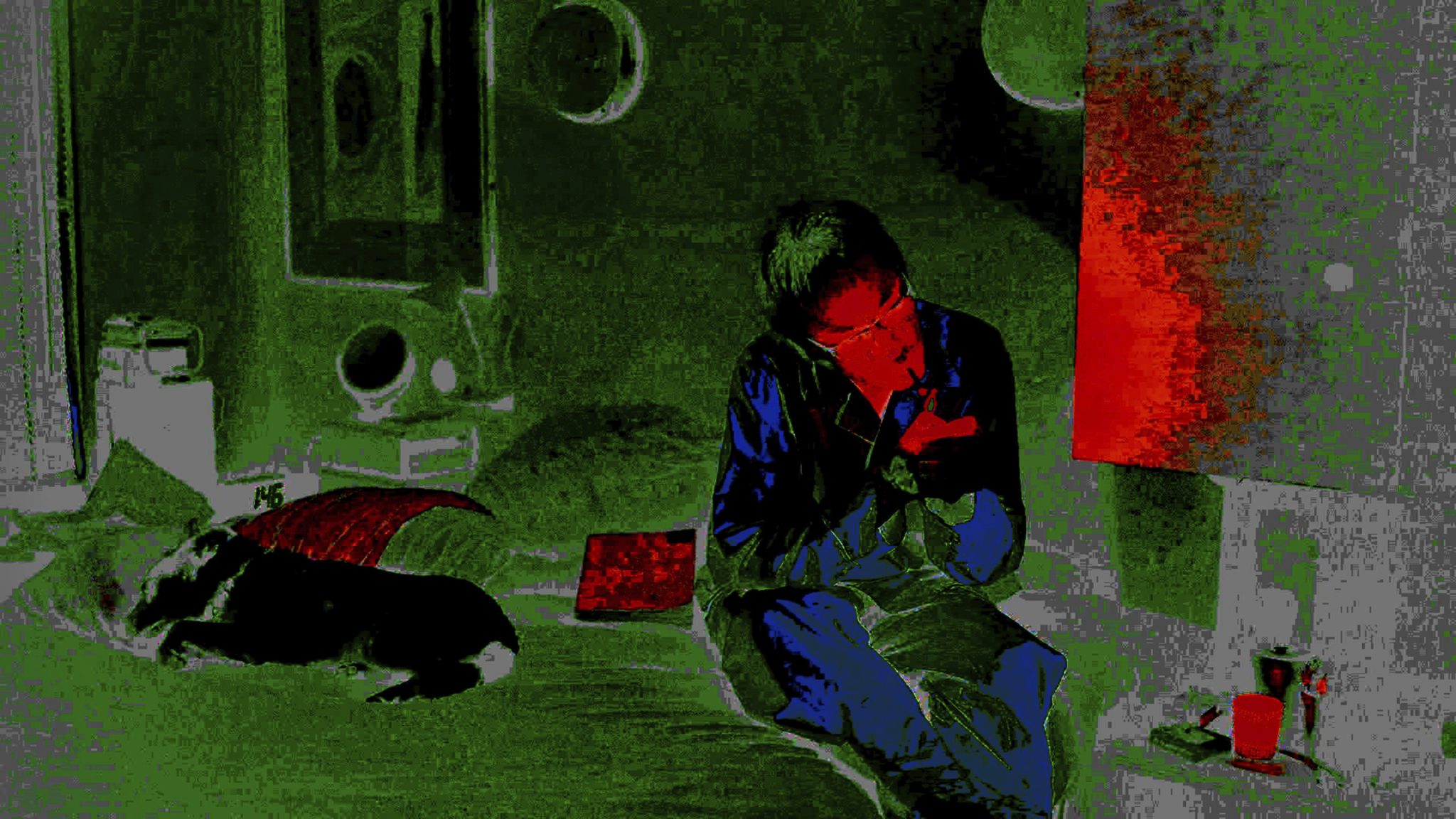

The answer is a frank “I don’t know”, whose complex and confusing nature takes us through a stream of consciousness, bringing together on screen various heterogeneous materials: an opening piece starring the director himself, desperate for inspiration yet obsessed with writing, doing so almost collapsed from bed; films from universal and French cinema, personal footage of Carax, fragments from his films, images of political leaders and internet memes, a few ambiguous scenes filmed specifically for the project (the Annette doll returns), songs by Nina Simone or David Bowie – and a lot of writing, in support of the essayistic exercise, but also as a homage to Godard, through Histoire(s) du cinéma (1989-90) and Le Livre d’image (2018).

In It’s Not Me, Carax is very much a Godard disciple; this first-person account of film history intertwined with personal history looks exactly like a possible offspring of the aforementioned films – the same graphic and big subtitles, from font to colour, the same abruptness in frame transition and in displaying quotes and grand statements about cinema. The Holy Motors (2012) director doesn’t necessarily have Godard’s political acumen or argumentative power but weaves together some generally fleeting and palimpsestic thoughts, sometimes about his own life and films, sometimes about the current state of the world, sometimes about the ontology of cinema – see this rather fitting pairing of the Muybridgian horse and Denis Lavant running in Mauvais Sang (1986). To be fair, though, Carax is more politically explicit than he’s ever been: he discusses images of war, old and new, the ghost of fascism and its reemergence in our day, the Holocaust and other genocides, issues not treated in depth but enough to sneak in things like an associative montage that puts Putin, Kim Jong Un, Trump, and Netanyahu together.

The hoarse voice Carax adopts and sticks to throughout the film could be a simple parodic emulation of Godard (a performance that seems to have annoyed several viewers), but I would rather say that the younger of the two enfants terribles is here merely self-mocking his own possession by the JLG spirit, his own unabashed pastiche. By including footage with Godard himself and a final voicemail message he left him, Carax seems, beneath all these layers, to express, not so explicitly, his own mourning that the cinephile community across the world is feeling.

It’s Not Me ultimately carries the aura of a memento mori, of something that must be left behind – several references to David Bowie, especially to Lazarus, bring a strange, poignant foreboding that Carax doesn’t elucidate necessarily. A segment of personal archive footage, shot on his phone, where the director follows his daughter during a walk along the Seine reminded me of the beginning of Bonello’s Coma (2021), where he also dedicates his film to his daughter, meditating on the current state of the world and what seems to be its incipient end. Both sequences have something of sheer vulnerability, a slight unmasking of the father behind the director. The film concludes with a dedication to Jean-Yves (Escoffier), Carax’s friend and great director of photography (Boy Meets Girl, Mauvais Sang, Les Amants du Pont-Neuf), who sadly passed away in 2003.

But it’s not as if Carax’s new film is bleak. On the one hand, it is moving, especially where, in the retrospective exercise of perusing through his filmography, from Annette (2021) to his debut films, you see a love and appreciation for Denis Lavant and his other collaborators. How wonderful to hear the director’s voice saying he never used a subjective shot, only to immediately confess “Oh no, I did!” and show you a young Juliette Binoche in a long close-up. On the other hand, beyond all this, as a friend called it, It’s Not Me is a film by a “player” (i.e. un gros gamin).

MERDE (i.e. shit) appears written all over the screen, partly a reference to Monsieur Merde in Holy Motors and the anthology film Tokyo! (2008), with Denis Lavant reprising his role here in short intermezzos and a scene where he walks around Père Lachaise Cemetery with the director. And partly an impertinent gesture, to occupy the sacred festival screen (i.e. the film had its world premiere at Cannes) with the non-cinematic, with the trivial, with “what the hell is this doing in a movie theatre” element. Boasting even a fake end credits and Bowie’s Modern Love played in its entirety – for the sole purpose of being listened to, as if Carax meant it as a special dedication for us on the radio – It’s Not Me includes many gestures of desacralizing and liberating the cinema screen precisely through its video-essay and composite format.

What’s great about It’s Not Me – and it obviously helps if you’re a Carax fan and reminiscing about his films and his favourite places tickle your cinephilia – is that the self-ironic grandstanding of the director’s voice and the gravity of the subject matter Film History are never allowed to become pretentious. In its exaggerations, self-indulgences, and first-person affectations, It’s Not Me is the sequel and ideal pairing to Sparks’ parody song When You’re a French Director featuring Carax himself, where he sings (comments) on the French director’s grand idea and superiority: “When you’re a French director/ You never smile, what’s the deal?”

If traditional cinema is, by analogy, a black-tie event, this new film by Carax is made in pyjamas. Shifting effortlessly from one subject to another and seeming highly improvised, It’s Not Me challenges good taste and maintains Carax’s reputation as an enfant terrible even at 63, but this raw, bedroom setting comes with the incredible intimacy and vulnerability of a sketchbook, which you often fear to show to the public.

Graduated with a BA in film directing and a MA in film studies from UNATC; she's also studied history of art. Also collaborates with the Acoperisul de Sticla film magazine and is a former coordinator of FILM MENU. She's dedicated herself to '60-'70s Japanese cinema and Irish post-punk music bands. Still keeps a picture of Leslie Cheung in her wallet.