Short films on MUBI – What are dreams made of?

A few days ago, MUBI opened its archive to its subscribers – colossal news for film enthusiasts. What does this mean? Hundreds of obscure and less obscure films can be watched whenever, without feeling pressed by time. From Jonas Mekas to Lars von Trier, Hedi Slimane’s collections or Nicolas Winding Refn’s restorations, any viewer can find its oasis of relaxation in these lists.

I started my journey with short films – this category that sometimes seems to be buried and forgotten inside film festivals – and that’s quite a shame, to say the least. MUBI curates short films mostly by director – and one can notice that the accent falls on the canonical directors generally associated with the avant-garde (Maya Deren, Hans Richter, Chris Marker, Agnes Varda, Jean Painlevé) and the contemporary directors, festival & critical darlings (Bertrand Mandico, Yann Gonzalez, Jonathan Glazer).

The list below includes some recurring motives: masks, disguises, delirium, female gaze; the fantasy of becoming someone else, of breaking social conventions. Last but not least, almost all the films here come up with the most original answer to the question “what are dreams made of?”.

Buffalo Juggalos (dir. Scott Cummings) – The Perversions Museum

Buffalo Juggalos are several individuals from Buffalo, New York, who live in a cult dedicated to a rap band. They paint their faces just like the members of Insane Clown Posse – and live with this mask every day – they are hooligans who want to remain anonymous and, at the same time, be shut out, cursed and feared of. Scott Cummings introduces them through a series of 30 portraits (in 30 minutes), by oscillating between filmed performance and documentary. As a result, the film offers a view inspired by Seidl on this violent culture.

Just like in Seidl’s works, it feels like you’re witnessing a kind of perversions museum (either images with these people going on the swings, braiding each other’s hair, repairing stuff and so on – activities that should bring some humanity to their act -, or rebellious behavior such as getting into fights, a crushed skull, sex in front of the camera, etc.). And this in-between area, which allows them to act in front of the camera, looking directly into the camera, leads to some very exotic-stylized images: a hypnotic smoke floating above a waterfall, a gothic wedding in an underground thicket, two llamas walking in an industrial hall. P. S. Buffalo Juggalos won the Main Award at BIEFF in 2016.

Our Lady of the Hormones (dir. Bertrand Mandico) and Asparagus (dir. Susan Pitt) – Magical realism + pornography

In Our Lady of the Hormones, Lune (Elina Löwensohn) and Lautre (Nathalie Richard) (“one” and “the other”, in French) are two actresses who wander through a forest. Suddenly, one of them discovers some sort of creature, half alive, half in a vegetative state, which can only move its tail. The two get very attached to the creature, they even give it a pet name – Zhivago, take it home, drape it with jewelry and make it the object of their erotic fantasies. Their home already looks like something coming out of a campy trip, an altar of bourgeois antiquities, where moss and climbing plants bathe each other. Lune and Lautre start competing for the creature’s attention – but it soon gets bored of the two ladies’ whims and wants to go back to the forest. Dissected in several episodes “narrated” by Michel Piccoli, the short film is full of macabre and meta jokes, and the possible clues on the creature’s appearance, most probably a hormonal hallucination, are just delicious.

Asparagus is one of the most flamboyant and irreverent animations I have ever watched; it’s about looking for one’s own sexuality (a lush garden, where the most beautiful flowers grow, in the most diverse forms, the asparagus finally appears, a phallic-shaped plant, which becomes delicate, almost feminine once reaching maturity). Basically, what starts as a series of individual feminine experiences (the protagonist is locked in her red dollhouse, goes to the toilet, looks out the window), eventually turns into a metaphor for women’s disguise in society. The protagonist doesn’t leave home without putting a mask on and repressing her own ideas (and how suggestive, her house is stuffed in her purse, and in the end, all things come to light, levitating in around a theater hall).

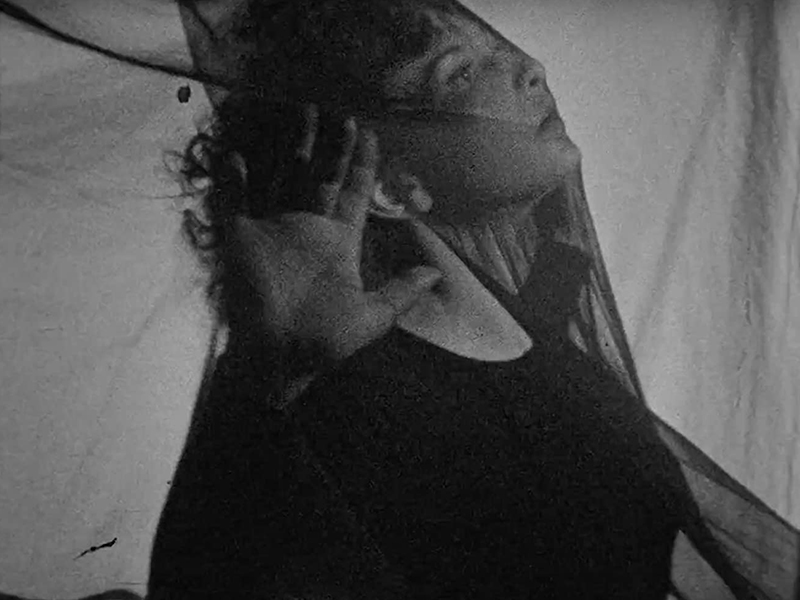

Meshes of the Afternoon (dir. Maya Deren, 1943) – Domestic torment

Although Maya Deren is part of the 1940s American avant-garde cinema, her films have little in common with Stan Brakhage, Kenneth Anger or Shirley Clarke – but rather seem to derive from Georges Melies himself. Meshes of the Afternoon, her best-known film, starring herself and her partner, filmmaker Alexander Hammid, is at the confluence of trance movies (P. Adams Sitney) and psycho-drama (Thomas Schatz).

After she arrives at home, a woman has a recurring dream about the sequence of actions she has gone through shortly before she fell asleep; each time, however, the current dream follows the previous one, so it slowly gets darker.

What is this film really about? First of all, it addresses a kind of domestic torment (a house where nothing is in order, the phone is taken off the hook, the bed is a mess, like it has been turned upside-down by someone else), probably associated with a lack of identity (a place that is no longer consistent with the protagonist, which the protagonist no longer recognizes). Secondly, it’s a surreal experience associated with femininity – unlike Bunuel’s anthological film, An Andalusian Dog (1929), here we have access to a purely feminine experience, which is not filtered through the eyes of any male character. In fact, Hammid’s character, the presumed husband of the female character, appears only inside the dream, it’s a projection of the protagonist’s messed up mind.

Outer Space and Dreamwork (dir. Peter Tscherkassky) – Found Footage Cinema

Several short films by Peter Tscherkassky (one of the representatives of the avant-garde found footage cinema in Austria, along with Gustav Deutch and Martin Arnold) are available on MUBI. Perhaps, the best-known would be Instructions for a Light and Sound Machine (which condemns Sergio Leone’s famous The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, in an abstract test on masculinity) or Manufaktur (a montage of commercials which go on faster and faster, more and more chaotic, being the object of a consumerist parody).

I, myself, chose two short films that use the same film as a source – The Entity, 1982, directed by Sidney J. Furie, a conventional horror about a poltergeist-type creature that torments the protagonist, Carla Moran, who can’t make anybody believe her. Tscherkassky uses a physical method to manipulate the film reel in order to reconstruct a new narrative of the film – especially in Outer Space, the protagonist is no longer tortured by an external entity, by a supernatural force, but she herself seems to be the one with whom she fights; Outer Space is built as an increasingly aggressive psychotic episode, which gets more and more difficult to watch/decipher.

However, the narrative in Dreamwork focuses on the protagonist’s sexuality – quite similar to Meshes of the Afternoon, here the protagonist comes home, gets her clothes off, falls asleep and dreams of all kinds of sexual interactions (consensual or not). For example, from one point on, Tscherkassky uses an editing style to give the impression that the camera is abusing Carla Moran. In such a self-conscious type of film (practically, Tscherkassky recycles well-known or very conventional genre films, to which he attributes new meanings), it’s clear that the emphasis is on the relationship between art and the viewer – the way Hollywood/advertising products are edited and built vs. what art film has to offer without any compromises.

The Fall (dir. Jonathan Glazer) – Social Parables

Jonathan Glazer’s short film (Under the Skin, Sexy Beast, Birth), The Fall, doesn’t really have a narrative logic, but works as some sort of sinister experience. It focuses on an execution: several masked people brutally shake a tree, from it falls another masked individual, the victim; without words or explanations, he is dragged to the murder scene, where he is thrown into a well with a rope around his neck.

The film rather bets on the atmosphere, created by the symphony between the camera movement and the alienating soundtrack (Mica Levi) – a back-and-forth between the victim’s point of view and the aggressors’ false subjective angle. Ontologically speaking, all the information is actually there: the victim is also a masked man who tries to run away from the others, for one reason or another; what made him leave, did he do something wrong to them, or he just wanted to be alone? The lack of any explanations (or any premises that might lead to this part) is quite disturbing – and reflects some sort of social stigma – where, most of the time, bullying has no specific reason, it’s just a heinous hunt and that’s it.

Journalist and film critic, with a master's degree in film critics. Collaborates with Scena9, Acoperișul de Sticlă, FILM and FILM Menu magazines. For Films in Frame, she brings the monthly top of films and writes the monthly editorial Panorama, published on a Thursday. In her spare time, she retires in the woods where she pictures other possible lives and flying foxes.