Ashes and Diamonds. The cinema of Alice Guy-Blaché | Panorama

Our new column Panorama seeks to call into question current films, classic masterpieces, remakes, evolution of the genres, social situations reflected in films.

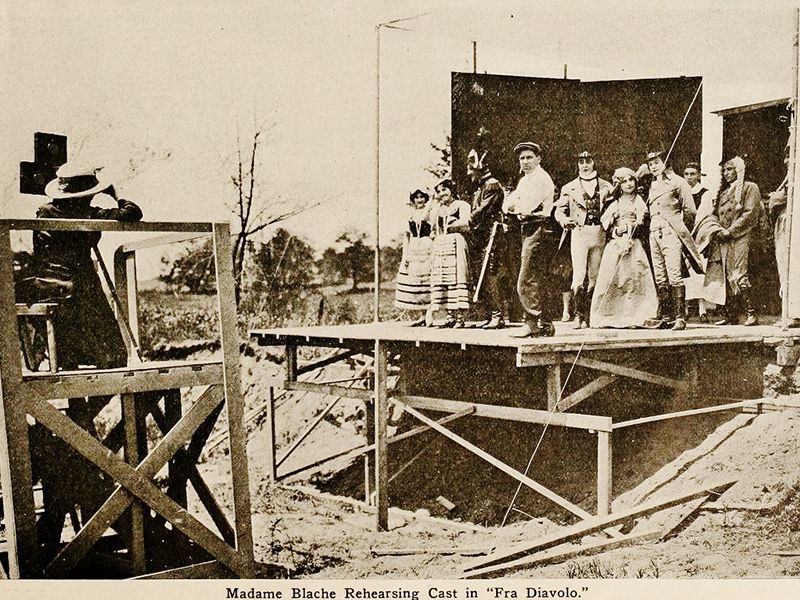

Since the second feature of our monthly column Panorama comes out in the women’s month, what more classic way of celebration than by probing the history of feminist cinema? Therefore, March brings to the fore the films of Alice Guy-Blaché, the first female filmmaker in history, the first woman to open her own film studio and the first female immigrant to make the first film with an all-black cast in the US; why was she forgotten and how did she come to be reconsidered as a matter for debate, 125 years after the birth of cinema?

Ashes

Ironically, the most notorious phrase used to describe French filmmaker Alice Guy-Blaché (June 1, 1873 – March 24, 1968) is “the most famous female filmmaker you’ve never heard of”: from about 1000 films she made in both France and the United States, only 150 will have survived – the history of this extraordinary filmmaker is still in the making, even today (the most recent example, the documentary directed by Pamela B. Green, Be Natural: The Untold Story of Alice Guy-Blaché, narrated by Jodie Foster; and, more importantly, the recent recovery of A Fool And His Money, a film with a colored cast, empathetic and glorious, made three years before DW Griffith’s infamous A Birth of a Nation). It’s incredible how much freedom of expression she had at Gaumont studios, 50 years before women even had the right to vote in France. Most of the recovered films are from the times when the filmmaker worked in France, whereas the films she directed in the US, almost all of them were lost. There are so many things that she did in cinema that were a first – and they are no myths – that it seems unimaginable at first glance that her name and work have remained unknown for so long. Rediscovering her is necessary – without her, far fewer pioneering female filmmakers would probably have had the courage to work in a field that is essentially masculine, and her dual minority status (immigrant and female in American cinema) carries alone an unprecedented element of feminist dissent. Despite the efforts of erasing her name or diminishing her creative contribution (either by crediting the DA’s for her films or by making them lost), Guy remains the incandescent spirit of all female filmmakers, of any color or nationality. So, just as the history of men’s cinema, which has the upper hand, does not lack representation and its course is clear, the history of women’s cinema started on the wrong foot and it’s filled with gaps – just like Guy was forgotten, maybe there are hundreds of female filmmakers worldwide who suffer from invisibility. Guy’s case is probably not unique – and unfortunately not the last of its kind. It is unclear, then, why the interest in contemporary women’s cinema is that low, given that, as I will show below, emerging filmmakers have managed to work and prosper in a time when voting was a utopia. When I think of the ill-fate of Guy’s filmography, I imagine the reverse scenario in which women would have had the courage to take over the fields claimed by men, and then everything would have been turned upside down – much like in the progressive parody directed by Guy, Les résultats du féminisme / The Consequences of Feminism, where genders role are shifted – it’s the men who stay at home and are harassed by women. I don’t mean to say that erasing Guy from history has led to parity between men and women in the film industry, but it’s certainly proof that no matter how valuable the latter are, their names will always fade compared to men’s.

The fact that Guy, who made films at the same time with the Lumière brothers and Georges Méliès and kept working long after they retired from the industry, has been erased from the collective memory has to do with both a terrible misfortune and a cover-up. Until 1912, films didn’t feature credits; when people actually started searching for these films, they were scattered through barns, cellars, and lakes. Her films, most of them made before that point, were lost; not to mention that the procedure for crediting the films is quite meticulous, because the themes and techniques were easily borrowed among the few early filmmakers. To that effect, in the absence of a theoretical basis or a cinematic paradigm, the filmmakers copied each other, and many of the films came out as a reaction or even a remake of the already existing films. It’s no secret that, as Alison McMahan states in Alice Guy Blaché: Lost Visionary of the Cinema, the first films lacked the revelation of stories, and rather served as a technical tool. Films were samples used in selling optical equipment – when the creators introduced their equipment, they presented some experiments made with the camera, in order to show its technical features. This detail somewhat changes the outlook on early cinema, so then, experiments such as film colorization, phonoscènes (a sound recording in sync with the motion picture, usually singers performing and lip-synching to the sound recording), superimpositions and slow-motion aren’t born from the need to create interesting stories, but to attract buyers.

In any case, this detail is not of minor importance, but it’s a key element in the claim on the narrative film; if Guy is without a doubt the first female filmmaker in history, she may very well have been the first director of a narrative film. Until 1903, these small experiments were figurative-illustrative, small slices of ordinary life, “attraction films”, mostly made by Louis and Auguste Lumière; of course, attraction films continued to be made even after 1903, but they became more complex, they showed a greater interest in the aesthetic form (later giving birth to the documentary film itself). But Guy was interested in stories – and her first narrative film, La Fée Aux Choux / The Cabbage Fairy (1896), a charming one-shot gag with a fairy pulling babies out of pieces of cabbage, was a real hit – it was sold in 80 copies and was remade at least twice, because the original film stock kept deteriorating. Guy picked up the same narrative thread in Midwife of the Upper Class / Sage femme de la première classe (1902), with a couple who want to buy a child from this fairy-saileslady. Also in 1896, the Lumière brothers released their first attempt at a narrative film, based on a common gag: L’Arroseur Arrosé, the famous short in which a gardener waters the garden, but a man keeps stepping on the hose and, thus, switching off the water flow, and when the gardener looks into the hose in confusion, he suddenly gets all wet. Film historians go so far as to credit both the Lumière brothers and Guy for the first fiction film – although, in both cases, the story is minimal. However, ironically enough, film historians had primitive notions regarding narrative film (everything that is not a single shot, or that uses a close-up at the beginning and end of the film, is automatically considered to be fiction); as history shows, none of these arguments can be associated with the narrative film, not entirely at least; a close-up without a story to back it up cannot be considered fiction in the first place, and an attraction film could very well have been made out of several shots and still remain a simple mundane illustration. Guy herself winds up making an impressive amount of films based on unique gags (a walking bed, an enchanted piano, a bouncy mattress), which only get more and more complex with time; here are just a few of them that I felt inclined to mention: How Monsieur Takes A Bath, about the ridiculous nightmare of a man who puts all the effort in undressing himself, but the clothes keep reappearing on him; Turn of The Century Surgery, where a surgeon cuts off all the patient’s limbs and saws new ones instead, then wakes him up with a bit of fresh air, and he’s as good as new; The Cleaning Man, about a servant who instead of cleaning the mansion, wrecks it from the ground up – the breaking point, people come one by one to the living room, stumble upon pieces of cement, and then fall headlong on the neighbors downstairs who are reading the newspaper.

Diamonds

La Souriante Madame Beudet (dir. Germaine Dulac, 1923) is considered the first feminist film avant-la-lettre – although both Guy and Lois Weber addressed overlooked female issues at the turn of the century. In my opinion, it would be wrong for every pioneering filmmaker to contribute to what we consider to be feminist today, without any of them having a clear intention to overthrow the patriarchy. Despite the fact that, in retrospect, Dulac had some feminist intentions, while Guy was only flirting with them (and so, in a context that is already male-oriented, you need to be incisive to succeed in conveying a message), Alice Guy’s films had a slightly subversive irony, especially the series of films of the “battle of the sexes” variety: for example, in Les résultats du féminisme, Guy overturns the hetero norms of normativity in a utopia with stay-at-home men and thug business women; this insane idea leads to an indescribable chaos. Also, in Madame’s Cravings (1906), she parodies several social stereotypes related to motherhood, the belief that it revolves around the compulsive cravings of the pregnant woman. Most films about couples see them arguing and then miraculously reconciling – in A House Divided, for example, the husband and wife can no longer stand each other, but live in the same house. In order to put an end to their quarreling, a court order is issued requiring they write letters to each other, but the tiring bureaucracy makes them reconcile. The happy ending is commonly used by Alice Guy, and is usually an element infused with a slight melodrama: in Matrimony’s Speed Limit, a penniless man receives an inheritance from an aunt, provided he marries until noon; his girlfriend is nowhere to be found, so he sets off looking all over for a wife, approaching all the unknown women in town. It’s like a ticking clock, his girlfriend is also looking for him, and when he finally comes to rest, just a few minutes before missing the deadline, he sees a cart approaching him and lays on the road, hoping that it will spare his suffering – but his girlfriend riding in the very same cart sees him, and eventually so does he, and they both happily go through with having the ceremony right there in the cart.

Alice Guy’s three most important films also run longer, and two of them are sprinkled with hints of melodrama: the first one, Falling Leaves, is about the tragedy of a young woman with an incurable disease; hearing that she will die at the end of autumn, with the last falling leaves, her younger sister starts to put them back on the tree branches. The second is Guy’s only surviving feature film, The Ocean Waif (1916), the story of a young woman abused by her foster father, who runs away from home and reaches an abandoned mansion, where the ghost of a girl lives, according to local mythology. A bourgeois writer and his valet wind up in the small location for literary inspiration, but they meet Cinderella, scared of mice; the writer and the woman fall in love, and he also manages to finish his novel. What’s really impressive about The Ocean Waif is the way Guy succeeds in going for the right framing, focusing on the characters’ faces and details; one can notice that not only the actors’ performances, but also the staging have reached the next level. The complexity of the mise-en-scene can be also seen in The Birth, the Life and Death of Christ (1906), a saga about the key moments in the life of Jesus Christ – and here, she skillfully uses superimpositions (invisible angels watching the baby Jesus, mirroring those who guard his tomb), but also a considerable number of extras, which enriches such a static shot, giving it depth; plus, unlike other early films that dramatize the life of Christ, Guy also focuses on female figures.

In hindsight, female filmmakers will become more visible over time, also because their voices can no longer be completely ignored, with the emergence of the second wave of feminism in the ’60s: the aforementioned Germaine Dulac, Maya Deren, Lotte Reiniger, Chantal Akerman, will all be acknowledged, at least in a theoretical sense; the fate of Alice Guy, as well as of all the pioneering female directors, could not be softened; Alice Guy will die with the bitterness of not being able to retrieve most of her films, and eventually, with age, she herself will forget about them. Personally, any effort to honor her name is significant (on that note, I highly recommend the essay written by Flavia Dima for Girls on Film) – because figures like Guy define our collective identity and give us the impetus to grow further, and also because, without her effort to float above it all, we probably wouldn’t have had so many emerging female filmmakers, in an industry founded and shaped by men. It’s disastrous, at the very least, that we hear the names of the Lumière brothers so often, that we regularly go back to Georges Méliès’ films, but it takes so much for someone to even dare throwing in one title from Guy’s vast filmography, who not only was their contemporary, but held her own and even persevered in making films long after they quit.

Journalist and film critic, with a master's degree in film critics. Collaborates with Scena9, Acoperișul de Sticlă, FILM and FILM Menu magazines. For Films in Frame, she brings the monthly top of films and writes the monthly editorial Panorama, published on a Thursday. In her spare time, she retires in the woods where she pictures other possible lives and flying foxes.