Charles mort ou vif and E nachtlang Füürland – A Swiss Tour

MUBI is offering a highly interesting retrospective of the Locarno Film Festival, consisting of a few important titles that have been part of its selection across the years (ranging from Pedro Costa to Pasolini). As one would expect, amongst these films there are also two Swiss films which are both very good. A country with rare, yet unmissable images: it’s as if the Swiss filmmakers would abandon any sort of „maison” neutrality when it comes to the act of filming, wisely choosing their side. Their side is that of images that contain in themselves honorable struggles and characters who are burning on the inside, animated by inextinguishable fires.

Charles mort ou vif is the debut film of Alain Tanner, who is the most important Swiss filmmaker after Godard. Not much has been written about Tanner in Romania, although his career peak in the ‘70s covered an elegiac evocation of the year of ’68, and of its already-vanishing lights, which was an achievement that was hard to parallel (maybe only by Philippe Garrel). Charles mort ou vif forebodes all of these shattered hopes, all the battles fought in the name of the beauty of gestures, in an elementary narration in which Marxist dogma is sweetened by a hippie, bon vivant atmosphere, in which vehement slogans meet bohemian languor halfway, and then everything is postponed for the next day. What else did the revolutionary moment of ’68 mean for most people, if not an extraordinary chance to idea around in spartan apartments, planning on how to set the world in motion again and again, from sunrise to sunset?

It’s the same here: because in Charles’ life, who is a director of a watchmaking company (which is a family business), what takes place is rather more of a transfer from one routine (bureaucratic, bourgeois, hypocritical) to another (modest, authentic, open to possibilities) – and not a radical rupture. Tanner’s idea is to present Charles as a soft and apathetic man (and François Simon’s slim, wrinkled face contributes to the effect), an opportunist swaying to the wind’s blow, an enterprise owner that is captive in a worthless life. There is nothing stranger to a man like this than the impulse to take life into his own hands and reconsider everything – but, still, that is exactly what happens. Did Charles turn into a different man overnight? Rather, Tanner says, that if even such a marionette of a character, who tolerates interactions with other people as well as one would enjoy being whipped, is able to take the step of escaping from the murky and deceitful life that he has waded into all the way up to his neck, then things can no longer be tolerated. Charles is an inert hippie and ’68 revolutionary: the choice to be like this can be nothing else than common sense; being something else would mean ending up like his own son, a thick-skinned businessman, who has already vigorously put his hands on the family business.

And so it goes that, out of sheer luck, Charles stumbles upon a couple that is much more terre à terre (he has a beard like a woodcutter, she wears her hair long), who initiates him into the lasting pleasures of life: cooking an honest meal, taking care of animals, and other such simple things. Their co-living conditions (Charles abandons everything and moves into their home) is at times ecstatic, at other times stormy: meaning alive, lived with intensity, without simulations, in the midst of quotes that are emitted daily and self-assuredly, with work that does not leave any space for trivial thoughts. Does such an experiment truly work in a world such as ours? Tanner doesn’t seem to have any illusions about this, either. It’s hard to find a more pessimistic end than this, in which the bourgeois noose tightens right up until it ends up strangling, and the closing images – tall high-rises, multi-lane highways – seem to be cut from an American B-series sci-fi from the ‘50s, where it’s unclear where the threat is going to attack from: from above, or from within the people themselves.

E nachtlang Füürland shares with Tanner’s film the same masochistic capacity to investigate a Zeitgeist that, as we already know, will not meet our expectations. We can also find in it the increasingly cozy mix between radical acts and the inability to enact their particular philosophy. Or, to express myself in ’68 lingo, here we can see characters that have something to say, but they don’t know what exactly that is. Especially Max, who’s a radio announcer, wearing turtlenecks, wide glasses perched upon his nose and sideburns just like it was fashionable in 1981, when the film’s plot takes place, and also sporting a sort of existential angst that doesn’t seem to give him any peace of mind. Just look at Max, at the end of a sleepless night, when he finally feels that he has finally found the moment which he can seize, but failing miserably at it right in its most decisive moment: instead of reading the pamphlet that he feverishly wrote with a one-night-only friend over the radio, in order to end his broadcast on a climax and to blow up the institution of the Radio itself, at least on a symbolic level, Max gestures with his hand that the show is over. The man is defeated, and the entire film, which has itself built up to that very moment, deflates in an instant. A grand moment of cinema, made out of nothing more than the ridiculous sight of a man that is growing old. What follows is a scene in which Max drunkenly crashes his banged-up car in a parking lot, making things even worse. And credits. Meanwhile, we have unwittingly just witnessed the barely noticeable, yet irreversible decline of a man. What could one ask more from cinema, than this dreamlike state in which we wake up, akin to Max, in an empty parking lot, with all of our emotions messed up? Clemens Klopfenstein and Remo Legnazzi’s film is a very pleasant surprise.

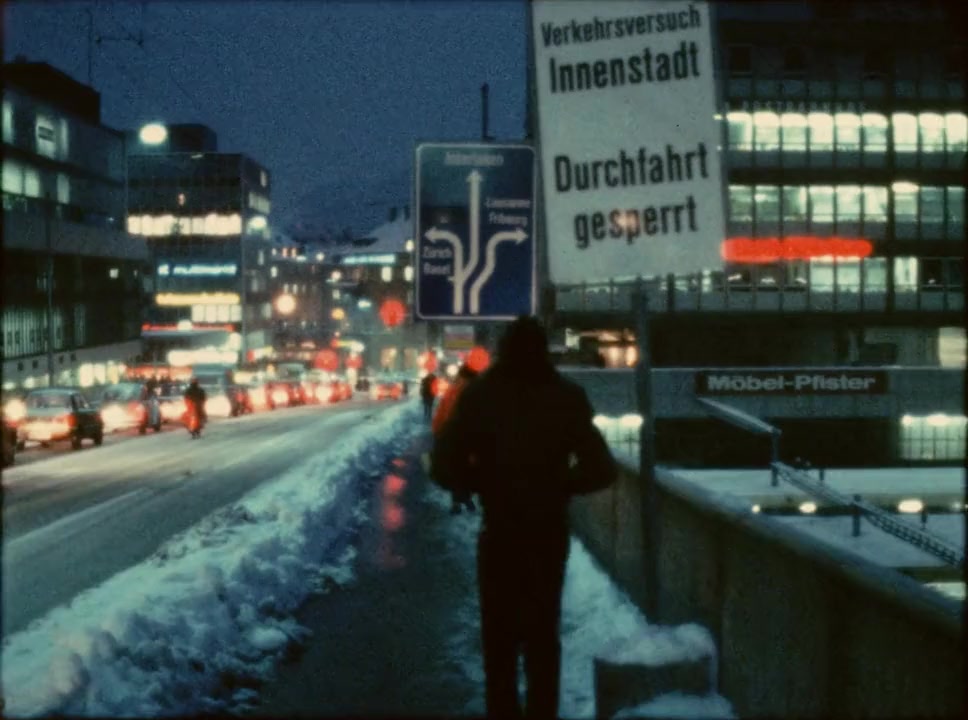

What the two directors create within Max (Max Rüdlinger, who has something in between Jean Yanne’s hairdo and Serge Daney’s profile) is an overwhelmingly endearing character, who quivers with life exactly because he evades any kind of archetypal interpretation. Suffering from love but capable of manifesting a semblance of dignity, disoriented as to his own life but lucid when it comes to society, at times jagged and irritable, at other naive and humble, and so on. His trip through wintertime Bern, bustling with overcrowded pubs and slippery roads, juggles around with what’s in its reach: a town that was yet unseen on the big screen, which was just waiting for a chance. And the chance came under the form of some directors who, seemingly conjuring Cassavetes, construct their film just as they would make a direct cinema documentary, in which the camera follows an individual around and frames its composition in any way it can, either decentered and out of focus, or too close, unpleasantly fumbling for the appropriate distance, that always seems unattainable. What’s sure is that this entire formalistic game works, because there is always the sensation that form has not preceded content, but that it was the only fully justifiable option. What do we see in this film? A fiction in which a disoriented man sees himself forced to pull the curtain on everything that his youth entailed? A documentary about a blueish, snowy night in which people slowly go to sleep? Or a hybrid formula, about a man that is walking around through a landscape that was already there? In any case, here we have a film that talks about the various geographies to the same degree that it talks about time. It’s a challenge that must be supported on any given occasion.

Title

Charles mort ou vif

Director/ Screenwriter

Alain Tanner

Actors

François Simon, Marie-Claire Dufour, Marcel Robert

Country

Switzerland

Year

1969

Film critic and journalist; writes regularly for Dilema Veche and Scena9. Doing a MA film theory programme in Paris.