Footnotes: Hervé Guibert and Cyrill Collard’s second-to-last lived experiences

By chance, a few days ago I was reading Edgar Morin’s recent work, Leçons d’un siècle de vie, written with Sabah Abouessalam. Published in late spring 2020, the book is rooted in the shifting sands of the pandemic statistics and ideas, being an intellectual snapshot of an early time that now seems primitive. Not that this would invalidate Morin’s discernment, especially since he is perfectly aware of the prematurity of the moment. But for the reader, it awakens a normal – culturally speaking – desire for rewriting and updating. Among the challenges that Radu Jude launched with his Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn, the one of incompleteness, invoked in the subtitle Sketches for a Popular Film, proved to be unexpectedly thrilling precisely because its instability was self-declared. Thinking for a long time about those who showed us the power of rewriting in art, I came across some who have empowered rewriting in life. Among them, modern saints Hervé Guibert and Cyrill Collard.

The last years have been in the first person. In thoughts, in actions, under the euphoric aspects of identity politics or the threat of a virus that manifests itself in myriad ways in the intimacy of each life that it touches, the interpersonal – nothing other than a self-effacing personal – seems done for. High art, a complex institutional mechanism, has mounted an offensive attack against the so-called marvelization of popular culture through the accelerated validation of the me-me-me (author-narrator-universe) formula; in this particular logic, opposed to the mercantile precautions espoused by popular art, lies the immediate experience of artisans. Of course, none of this is new, but it’s happening now, more than ever.

However apprehensive I might be, I don’t blame such a state of affairs. On the contrary, I am one of the admirers of the first person, and I am able to recognize its potential in mapping the age of the coronavirus. I feel this urge so heavily that I find myself returning to the art that was born of another pandemic, the HIV one. Then, for a price that was all too heavy – and which is still being paid for to this very day -, the school of thought regarding disease was forced to rapidly come of age. After the third person, with its discourse, its statistics, its metaphors, its double standards and so on, proved itself to be poisoned, the experiential art of the seropositives, especially the kind that came cloaked with the heavy aura of a testament, remained one of the few moral paths of gazing around at the pandemic.

As Romania lost the head start on the early discourse surrounding HIV/AIDS (or “the homosexual cancer”), the disease arrived to a much more clarified agora. Of course, this does not mean that the pandemic wasn’t instrumented here (and everywhere) against the homosexual community, but the almost decade-long delay means that things had more time to settle. Furthermore, if the texts that I have read from the time declared HIV as the virus of promiscuity, then it is not the homosexual that is promiscuous, but the communist society which seemingly swept the rising local infection rates among children [1] under the rug. In any case, one must not forget the era’s fearsome homophobia. Nor the fact that, even during democratic times, homosexuality was still a crime in Romania, until 2001.

And so, the two books that I plan to talk about seem all the more unusual. It just so happens that both of them are French, self-fictionalizing, from the nineties, belonging to HIV-positive men, just as it so happens that both of them were filmmakers and that both of these books birthed films. The first book – To The Friend Who Did Not Save My Life by Hervé Guibert – was published by Nemira in ’93 (translated by Nicolae Constantinescu). The other one, enjoying more popularity, Cyrill Collard’s Savage Nights was translated by film critic Rolland Man and sent to the printing press two years later, as the most important title published at the transient publishing house of the New Cinema magazine. Before delving into them, however, I will also cite another unusual publication on the Romanian nineties-era book market, and that is Lionel Pover’s fabulous Gay Dictionary (published at Nemira and translated by Iulia Stoica and Felix Oprescu), so that I may give those times some spirit, and vice-versa.

*

CYRIL COLLARD

Filmmaker, writer, musician (1958-1993)

(…) In order to carve out a living for himself, he will end up successively working as a maritime assistant, photographer and, at times, as an actor. In his diary, published post-mortem, The Savage Angel, he talks about his sentimental education, that of a man that liked girls, but enjoyed boys even more: sexuality is one of the engines of his life. Starting in 1989, he started mingling with the cinematic circles. A filmmaker and a musician, he first worked as the assistant of René Allio, then that of Maurice Pialat; he directed music videos, short films and TV shows. Passionate about music, in 1985, he becomes one of the founders of the Cyr band, and records an album that is released by CBS-Epic. But the large audience will get to know him due to his books, Condamné amour, published în 1987, and especially Les nuits fauves (Savage Nights), in 1989, the story of his amorous travails and of the existential questions of a bisexual that mirrors him just like a brother.

NUIT FAUVES (LES)

French film, in color, by Cyril Collard

(…) More than just a simple film, Les Nuit Fauves was a true social phenomenon, an electric shock that was administered to the large audience and to the youths, in particular. Truly so, for the first time on the big screen, in France, the number one scourge of the end of the century, AIDS, was discussed openly, along with another important social phenomenon: that of bisexuality. Using a tone that is fair yet simultaneously excessive, Cyril Collard knew how to convince people of his hopeless sincerity: Les nuits fauves, an adaptation of his first novel, is one of the biggest cinema success stories of the past years. IT also gave us the chance to discover a promising actress, Romane Bohringer, who will, just as the film, be awarded a César in 1993, just three days after the filmmaker’s demise.

Hervé Guibert

Writer, French novelist (1955-1991)

At 17 years of age, after flunking his entrance exam at the IDHEC (Institute for Advanced Cinematographic Studies), he enters college to study philosophy and cinema, but only remains there for a month (…). Around 1973-74, he met Patrice Chéreau, with whom he will pen the script of his film, L’Homme blessé. (…)

The author of more than a dozen books, (…) Hervé Guibert provoked the emotions of his close circles, that of the literary, intellectual Paris, and eventually that of the large audience, by publishing To The Friend Who Did Not Save My Life in 1990. More than just a novel, it’s an intimate, romanticized diary in which he tells of his donuts, his uncertainties, his suffering as the AIDS patient that he had become. (…) Shortly after his death, TF1 broadcasted a video document about the last months of his illness, shot by Guibert himself, which provoked a beautiful controversy between the partisans of the right to show everything and those who denounced its morbid exhibitionism and its corollary, voyeurism, which flatters the spectators that are submerged in the obscene fascination of a body ravaged by illness and that is sentenced to death.

*

Two books lost in the media whirlwind of the nineties; and looking as such – “sex, passion, death”, yelled a small yellow band in the corner of the cover to Savage Nights. Funny; however, there’s nothing laughable about it; such publicity signals, shiny photos, violently colorful spots and boyish graphics are the inheritance of past times when books had an audience. Back then, a difficult and suspiciously-looking writer such as Guibert could be published in a popular series alongside Stephen King and Mario Puzo; the rules of the free market were still being written on the go. In our atomized days we would know all too well where each title could fit – To The Friend would go, let’s say, to Black Button Books, and Nights would be published by Pandora-M or Litera.

Usually, when a book is compared to its ulterior adaptation the latter usually comes across as ill-fitted. And the lion’s share of the discussions about books vs. adaptations seem to mostly take place within the bounds of banalities. In this case, however, the discussion can only be one; neither Collard, nor Guibert should be confused for their autofictions; but the ulterior films have something unmistakable about them – the body, the face, the contour of each of them. Yet another banality, one that belongs to cinema. I have endless sympathy for this fascination with small victories against time. And for the two of them, in the rhythm of art made with light speed despite the surrounding darkness, these two to three years that lapsed between paper and film reel seem endless. If we were to subtract the books from the films, the rest would still be considerable. Since, following the semi-colon, there would be a new, different way to regard death; the HIV-positives of the eighties are the deathly ill patients of the nineties. That’s easier to see in Savage Nights, most probably.

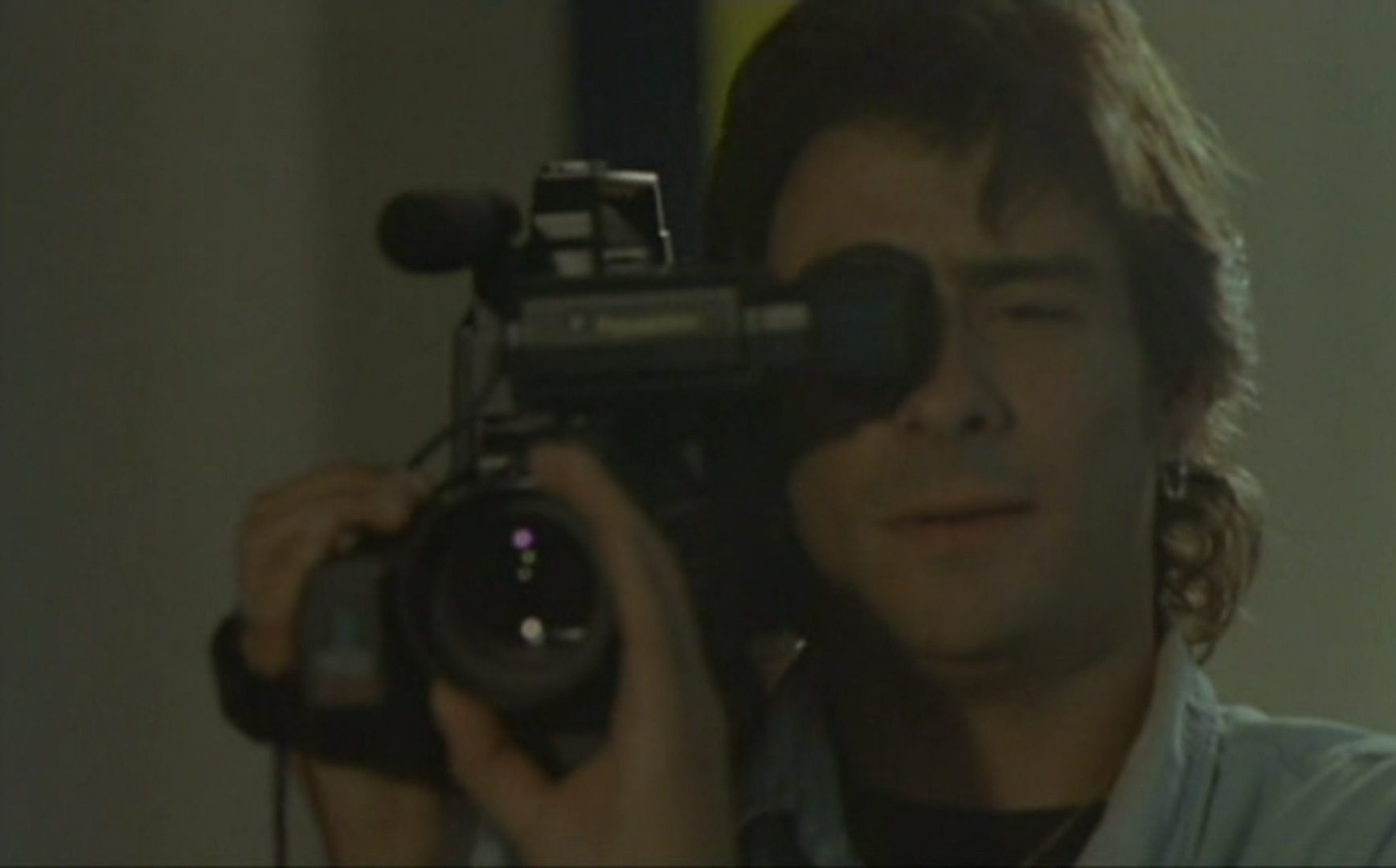

All the more considering Collard makes himself understood by employing the duality of his spiritual patron, none other than Jean Genet. At the beginning of the film, Jean (performed by Collard himself), a small filmmaker in the Paris of the eighties, awaits his turn on the hallways of a random hospital. The voice-over renders audible what he is writing down in his diary: that on the day of his return from Morocco he found out about the death of J.G.; on the 15th of April 1986, the protagonist’s second year as an HIV-positive man.

A writer, a filmmaker and a political activist, Genet created a path for homoerotic literature in his novels that sanctified pariahs in the forties; for him, manly miners turn to flowers, the stigmata of homosexuality turns to nobility, traitors are saints, and the damned in general are the ones to bless his romanticised egos. One could hardly overestimate his legacy in contemporary queer culture. Furthermore, in the seventies, he would travel to the USA and dedicate himself to the radical activism of the Black Panthers, and then to the Palestinian cause. That’s what is missing in the life of Jean („just like him, one day I will have to start taking action”), whose life is otherwise pretty Genet-esque[2]; and between these two strains of thought, the battle of insufficient time is waged. His wild nights, traversed by foreign men whom he asks to humiliate him sexually, help him forget about the virus. During daytime, he spends his time between shootings, a very young lover (Samy, played by Carlos López), whom he picked up at a random party, and a teenager lover (Laura, Romane Bohringer), whom he met at a screen test for a music video. Beyond them, a few lovers have to do with the change that Jean wishes for and often remembers. It seems like the colonial past of France is haunting him; he thinks about Morocco, Algeria and their bloodied pasts, he is fascinated by a love story between a French woman and a Maroccan man, and is entranced by the wicked murder of the woman’s son by the chambermaid of his hotel, and he enjoys fugitive passions with clandestine boys, yet he never manages to reach for the Molotov cocktail. Both the film and the book speak little of this. Anyone who remembers them can recall that the protagonist’s relationship with Laura is the one that made the history books – through its improbable wildness, its explosive sensuality, its sickly allure, the sickness itself, and so on. Yet the great advantage in writing this thirty years later is that one can avoid self-evident truths. Thus we arrive, in particular, to Jean’s relationship with Samy, which is not as tense from an emotional point of view, but which ends up being politically sabotaged. Since the boy, who is twenty, who has grown up in the violent life of poverty, gets increasingly involved in a French neo-nazi group whose ultimate goal is to shed the blood of Arabs. In the book, Genet’s saying that “only violence may put an end to the brutality of people” is little more than a hazy ideal. Jean never ends up facing the fascists, but he manages to look at himself in the mirror and to wish that his blood will be used as a weapon against them. Well, in the end, the film exorcizes its protagonist’s impotency and arms him with his own blood in the battle against the “alchemists”. And thus, by saving Sami, whose screentime is not more than a few dozens of seconds, and who in the book appears as an Algerian lover that Jean cannot help save from deportation, Jean turns himself into Genet; a hero.

“The hero is the one helping someone who is dying, the hero is you, and maybe me as well, the one who’s dying.” (To the Friend…). And for Guibert, the world became one of salvation. After all, the title speaks for itself. Its writing commenced on the 26th of December 1988 and lasted until the end of the following year, To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life, the first of Guibert’s books concerning HIV, is very different from Modesty and Shame, the film which would follow it. Since, chronologically, it made no sense – the camera is turned on half a year after the last full-stop of the book was jotted down; and it serves as a diary, as such, toward the unrepeatable. Which is both correct and false; Modesty and Shame must be understood as a cinematic fulfillment of the same ambitions for which the author’s literary auto-fiction had served as a vehicle. Both To The Friend and Modesty are discussed in diaristic terms, although none is a full-fledged diary.

In writing, things are less complicated. Although he mimics a diary structure, Guibert often uses memoirs and, I speculate, the fictional lubricant that is a certain Bill, the friend involved in the pharmaceutical business. He promises the narrator a shortcut to a so-called cure for AIDS, but the promise always slips through the patient’s fingers, even as despair makes him clench his fists tighter and tighter. Of course, Bill does not save his life and the illusion comes to an end in the pages of the book. But two quotes reappear in Modesty and Shame: shortly after the introductory generic, the voiceover confides about the first time it became aware of its tainted blood. Then, accompanied by an iconic Russian roulette with glasses – one poisoned with too much medicine, another full of plain water –, the same voiceover asks rhetorical questions about what happens when one is dying. At this latter moment I want to linger. Suicide is not something new to the author. Even back to his debut in writing, the terribly provocative and Genet-esque Propaganda Death (1977), describes not only the will to do it, but to record it nonetheless; In To the Friend, the author talks about a plan to get Digitalis through a fake prescription, thus ensuring an overdose. As translated on screen, I don’t think cinema ever gave us a more combative moment; but it doesn’t look fully true either. Guibert would have loved my misunderstanding. For cinema has conventionalized death to such an extent that it can only happen in two ways – documentarily, open before our eyes, as for that poor man who jumped from the Eiffel Tower at the turn of the century in the hope that it will fly, or fictional, crushed and carefully aligned in the “natural” order of psychology, continuity etc. Lying on the chair for a few good moments, his fragile body plays with our anxiety like in Hollywood clichés; but the lack of CGI makes us vulnerable, whether or not we missed the opening card, “a film directed and starring…”. And in the end, it says so: “one needs to experience something at least once before one can film it”. After all, whether he really survived or simply wanted to stimulate his reflections on death matters too little; the important thing is that, like Cyrill, he did not want to leave things as they were. Unfortunately, the cinematic treatment of his suicide attempt was not to be its final version for Guibert; he died on the 27th of December 1991, two weeks after a final, definitive attempt.

It has often been said that the two books play a trick on history by cutting the protagonists from the collective effort that overcome the pandemic was. Of course, neither of them wrote an intellectually-unchaining mantra such as AIDS and Its Metaphors (Susan Sontag, 1989). For the first person, no matter how rebellious – and those of Collard and Guibert are outright rebellious – does not have endless power; but it empowers itself from one rewrite to another. This makes it reactive, undefined, and, ultimately, ideal for destabilizing the art of an unstable world.

[1] Just as everywhere else, the HIV epidemic in Romania was a source of all sorts of tales, metaphors and spells. It is said that „the virus took a train into Romania”; Romanian Railways worker Teodorescu, a middle-aged man, whose job had made him travel all over the West, had gone to the hospital in ’85 suffering from capricious symptoms that eluded any diagnosis. But the patient’s regular visits from certain males visitors made things seem clear – Teodorescu wasn’t just a random victim of the West, but a mediocre victim; the homosexual, a foreigner that is carrying an ever more foreign virus within himself. And the legend continues to this very day: given that homosexuality and sex work were banned during the Ceaușescu regime, HIV was simply not supposed to be there, amongst Romanians. As such, the information was seemingly sealed away, kept far from the West’s scornful eyes until 1990, when the images from the Romanian orphanages toured the global press.

[2] But it is a night life; one that is confessed to others, yet no less broken from daily life. What’s important in the case of Genet – in The Thief’s Journal, for example – is that the aura of sexuality is not photosensitive, so it is unable to disappear in daylight. Vagrancy, meaning not just misery, but also rebellion, is inseparable from pederasty.

Film curator, writer and editor, member of the selection committees of BIEFF and Woche der Kritik, FIPRESCI member and alumnus of the film criticism workshops organized by the Sarajevo, Warsaw and Locarno film festivals. Teaches a course on film criticism and analysis at UNATC. He has curated programs for Cinemateca Română, Short Waves, V-F-X Ljubljana, Trieste Film Festival, as well as the Bucharest retrospective of Il Cinema Ritrovato on Tour in 2024 and 2025.