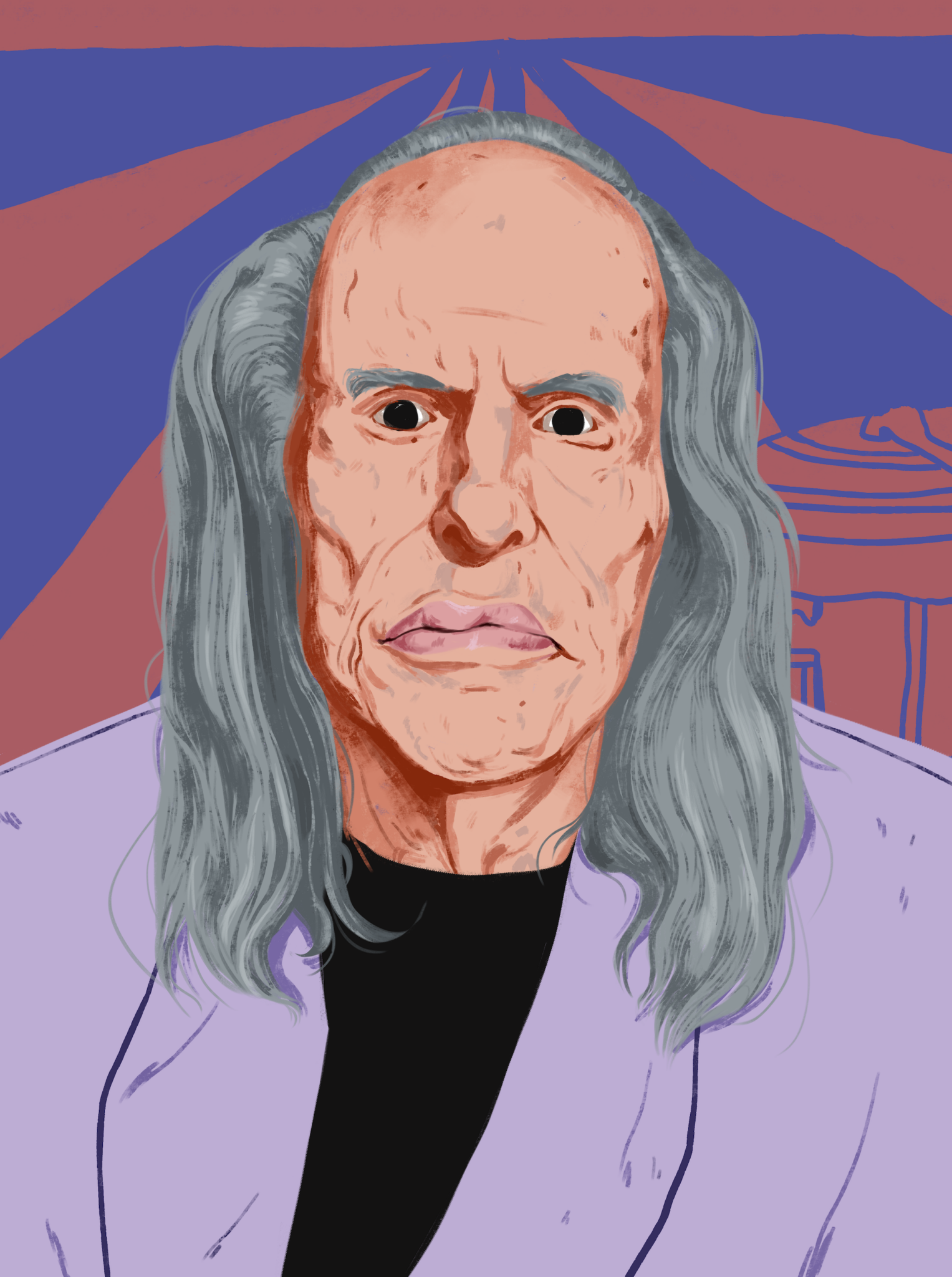

Kenneth Anger, the last American diva

Hollywood is the locale where people move, work, and die; nobody seems to have actually been born there. Kenneth Anger came as close as he could to this: Santa Monica, California, the youngest son of a so-and-so-middle-class family that owned a Super 8 camera – and so, as a child, he played cinema.

By the end of his teenage years, he’d understood the game’s rules. When Fireworks (1947), one of his earliest surviving films, ran into trouble with the law because of its promiscuity, Anger lied about his birthdate, turning 1927 into 1930, 20 years into 17, which is actually the age at which he had written the film, as if to convince himself that, although he was on the cusp of maturity, the game had remained all the same, as the essence of every game lies in the obsessive desire that something’s going to happen (to you).

Many of the films he made up to the seventies would turn out to be about this particular modern obsession that dominated popular culture, underground culture, politics, religion, and sexuality alike. However, their way of being, made on shoestring money, steeped in esoterism (Anger was an adept of Thelema, the occult religion prophesied by the infamous Aleister Crowley), make it so that it’s never quite clear what is really going on. The ones made after the year 2000, more than 25 years after Lucifer Rising (1972), have the sapiential sense of the end of history, as if, throughout the previous century, too much had happened at the same time, and there had been no time to understand it all: this is how his frustratingly ambiguous found footage films seem to me, with their Nazi propaganda (Ich will, 2000), cigarette commercials (Don’t Smoke That Cigarette, 2000), Crowley portraits (The Man We Want to Hang, 2002) and Mickey Mouse merch (Mouse Heaven, 2004). Anger was never truly famous in the eyes of a larger audience, although he was much more than yet another American Experimental Filmmaker. During the years of the New American Cinema, the experimental movement helmed by pauper mogul Jonas Mekas, Anger was called a pioneer, a grand maestro, and a seer of the new American dream of making films out of pure nothing.

“In memory of Kenneth Anger, filmmaker, 1947-1967” – that’s the title of an ad in The Village Voice that was paid by Anger himself, after Bobby Beausoleil, the star of Lucifer Rising and later criminal associate of the Manson family, had run away with his film equipment and raw footage.

In Fireworks, the young protagonist, played by Anger himself, dreams that – after an unsuccessful flirt – he is picked up and brutally beaten by a gang of mariners that are wandering around in the dark. In the end, the nightmare proves to be a masochistic dream, and this first-person position of the filmmaker within his own fantasy, brought upon by his own powers and for his own pleasure, is not at all easy to tame, not even nowadays, 75 years to the day. Later on, in 1967, Anger destroyed all the juvenile films that he had shot before this, and over the years, he presented the film in various variants. What fascinates me about Fireworks – speaking about Anger’s talent towards imposing meaning – are two shots that are almost foreign to the film, in the sense that they don’t look like anything else that precedes or succeeds them: the first, just a few second long, is a hand-held camera movement, up-down-left, that circles some urinals; the second, immediately following the first, is one second long and seems to have been shot in the same public bathroom, with Anger sexily laid out on the floor, stark naked, save for a white beret on his head, resting on his elbows and ass on the dirty floor. Nothing of these two shots is common to the overarching mise-en-scene of the film, which is otherwise academic, or rather schoolboyish, with dotted, perfectly intelligible meanings and signs: the seconds in question, instead, seem concocted and forced, yet not wrong, but rather anticipatory.

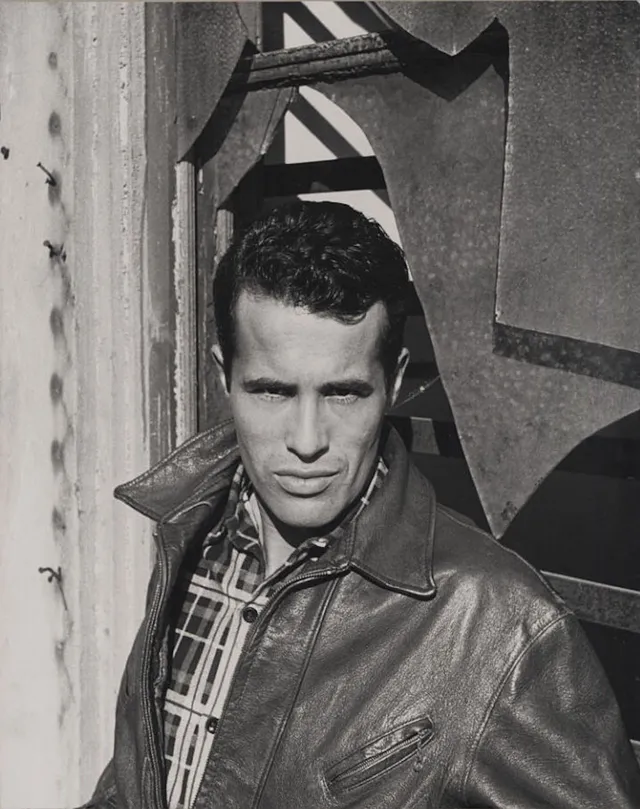

Scorpio Rising, his 1963 masterpiece, was to take his poetically unstable cinema much further. Beginning as a generic documentary about the biker reunions on Coney Island (of which he kept very few shots), continuing as an ensemble portrait of a Hells Angels-type gang, and eventually turning into a fascinatingly erotic little portrait of blonde biker Scorpio, a household Marlon Brando. Still, the film was not enough for Anger.

He needed a grand editing gesture: between motorcyclists and Jesus’ apostles in a Christian propaganda film, between dizzying shots of parties, initiations, training, and competitions, between the all-too-close-ups of the boys’ blue jeans and the lyric about blue velvet in Bobby Vinton’s pop ballad (in another film, Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome, Anger realized that superimposition – that is, juxtaposition, thus editing cut – are sexual acts). These hardcore boys became the new muses of Anger, since, in their hyper-masculinity, he also discovered a hyper-sterility; reduced to their essence, they resemble the mysterious actresses of his previous films (Puce Moment, 1949; Eaux d’Artifice, 1953), only more vulgar, more titillating in that they threatened death – their own and others’ alike.

It is said that Bertha Coler, his maternal grandmother, had been a set worker for the Hollywood industry, hence the filmmaker’s precocious cinephilia – yet nothing is nothing truly unequivocal in Anger’s biography, which he wanted – and made, then remade – to rest on the border the between inevitable and improbable. For example, the first films he remembers seeing were none other than The Singing Fool (1928), one of the first-ever talkies, a melodrama about the price of having success on Broadway, and Thunder Over Mexico (1933), a work-in-progress of ¡Que viva México!, Sergei Eisenstein’s unfinished project that fascinated the history of cinema through its homoerotic imagery and dramatization of pre-Columbian Mexican rituals. To anyone familiar with Anger’s cinema, mystical and sexual and spellbound by old Hollywood, the memory of this double bill is outright providential.

On the 11th of May 2023, we lost not just a giant of experimental cinema, but, indeed, the last American diva: a presence that seemed far away no matter how close she came to you, principally indifferent to her own image, yet perfectly obsessed about it. An unfulfilled diva whose abandoned projects surpass the ones that she managed to fully accomplish: “My dreams are big-budget, but my films are not”, he said to Harmony Korine in 2014 – a renowned, yet not quite famous diva. Moving between Paris, London, New York, and L.A., Anger turned into a flaming creature of contemporary life; with Alfred Kinsley and Jean Cocteau, Jonas Mekas, Marianne Faithfull, Federico Fellini, Alejandro Jodorowsky, Mick Jagger, Anton Lavey, Susan Sontag and Henri Langlois, members of the Manson Family – he said that he didn’t like Andy Warhol, and that as a child, he had once danced with Shirley Temple. A solitary diva, living almost in secret, far removed from the attractions of the contemporary star system, where celebrities are always close and “just like the rest of us”.

Film curator, writer and editor, member of the selection committees of BIEFF and Woche der Kritik, FIPRESCI member and alumnus of the film criticism workshops organized by the Sarajevo, Warsaw and Locarno film festivals. Teaches a course on film criticism and analysis at UNATC. He has curated programs for Cinemateca Română, Short Waves, V-F-X Ljubljana, Trieste Film Festival, as well as the Bucharest retrospective of Il Cinema Ritrovato on Tour in 2024 and 2025.