Oscars So Indie | Panorama

I – The rules of the game

It’s no news that every awards gala in the last year has taken place in hybrid-exceptional conditions (half on Zoom, half in physical format, and with increased safety measures). After the American Academy, along with all of Hollywood, enjoyed an old school gala last year, this year’s Oscars will finally take place on April 25, and it might not go as big as in previous years, but it will make sure to maintain its traditional glamorous mood (at least partially). The pandemic might be the main reason so many indie films, intimate slices of life, family dramas or movies about loneliness have finally managed to break through and make it in. A slightly better and more incisive lineup than in the past, precisely because it seems more attentive to ethnic, racial or sexual minorities; at the same time, as in any given year, these things are a simple diversion from the real problems the world is facing today. I admit that I returned to the topic of the Oscars after a few years of refusing to show any kind of interest in its bourgeois stance, it was just an event that I simply didn’t care about.

The main dispute between Oscar films and the rest of the world is that: 1) the nominated titles are sometimes accused of an Oscar bias, meaning that, in general, films about the heroic acts done by exceptional Americans are never left aside; and 2) there are only a few genres that fully address the triumphalism/climax of Americanization: historical film, family drama, the success story of masterminds, usually misunderstood scientists (cosmonauts, physicists, etc.), political drama. Over the years, there has been a film here and there that broke out of this crass stereotype, generally films that portray less flattering episodes in the American history (Spotlight would be one, Green Book would be another, both managed to win Best Picture), but one must always tap on the patriotic sensibilities (generally the war film, see 1917 or Hacksaw Ridge – I’m not talking about their aesthetics, but my argument is that the theme factor favors them in the competition every year). In any case, this evolution is most welcome – let’s not forget how accommodating, in terms of pleasing the audiences, were the early 2000s awards: Gladiator, Braveheart, even Forrest Gump, they were all a historical depiction of one individual’s greatness, his endurance in the face of adversity and escape from the scourge of society. Since Oscar films are the most privileged in terms of gaining international notoriety throughout the year, it’s obvious that these awards have become an institution and, moreover, like any governing body, it is based on unreliable biases. I can’t seem to understand, for example, why First Cow, Kelly Reichardt’s latest film, didn’t receive a nomination this year, as Eliza Hittman’s Never Rarely Sometimes Always, although both films have had an impressive festival circuit.

On the other hand, these very biases, which have become a classic over time, were the deciding factor in granting Romania a double nomination for the documentary Collective, although it didn’t come as such a big surprise for me. Andrei Gorzo explains the phenomenon – it is, as I mentioned earlier, another heroic story about the fight against injustice – and it is told by two key characters (the vigilante journalist Tolontan and the political figure of VV) from an invisible country, politically speaking. The geopolitical distinction is important – because it doesn’t make Collective a film relevant for the most important category, but it made it a suitable contender for the Documentary category and the Best Foreign Film Award. Empirically speaking, Collective might not stand a chance in the Foreign Film category, mainly because Druk/Another Round is most likely to win (since ex-Dogma Vinterberg is also nominated for Best Director), which members of the Academy must have anticipated, placing it in two categories. So they might expect that the real battle for the Best Documentary Award to be between Collective and Time, an example of cinéma vérité about a man sentenced to 60 years in prison (unless we also consider the adorable romance between a diver and an octopus from My Octopus Teacher). However, I believe that these two factors will tip the scale in our favour: 1) this is the first time ever Romania has received a nomination, and 2) the film’s topic – the people’s fight against the corruption of the authorities, which surely resonates in the post-Trump US. In any case, a double nomination is already a win for Romania, however you put it, but I’m sure this doesn’t mean that it will make it easier for us to get on the shortlists next year.

II – The players

Next, I will focus on the films in the Best Film category – like in the case of any gala of any kind in this world, in a few years no one will remember the titles that competed with the winner of this year’s edition, but only the film that took home the award. And many more years later, this award will just be another number in some irrelevant statistics. So the eight films in the race for the Best Picture Award are: Mank (dir. David Fincher), Minari (dir. Lee Isaac-Chung), Nomadland (dir. Chloe Zhao), The Trial of the Chicago 7 (dir. Aaron Sorkin), Judas and the Black Messiah (dir. Shaka King), The Father (dir. Florian Zeller), Sound of Metal (dir. Darius Marder), Promising Young Woman (dir. Emerald Fennell).

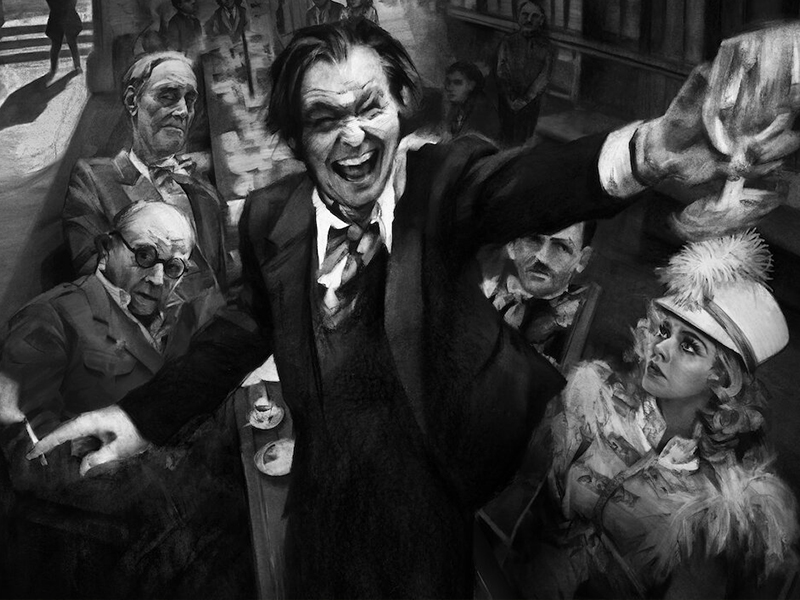

I will start, therefore, with a review of the key films of the edition. Every few years there is another indefatigable film about the history of Hollywood (i.e., La La Land in 2016, The Artist in 2011) – so David Fincher’s film about the mammoth Herman Mankiewicz, the screenwriter of Citizen Kane, was a soft spot, no matter how disastrous it would have turned out. Sure, Mank isn’t an affliction, but it’s not flattering enough to win the award for Best Picture (although it’s the most popular film of the year, with 10 nominations!), which rather makes it the last contender in line: not the fact that it looks and feels like a film from the Orson Welles’ days diminishes its charm, on the contrary, but the lack of any direction, it’s pretty much the gratuitous depiction of an era.

Returning to the American dream, Minari might be the closest to portraying this image – at the same time, I can’t think of a more human and low-key film than this one (an argument that, of course, overturns the whole idea of triumphalism) – it’s about a family for whom nothing seems to work, and there might be some specks of joy, but it’s not about some fantasy of getting rich, it’s just a Korean guy who dreams of growing his own farm in Arkansas, while everything is falling apart. The tomatoes go bad, his helper is an eccentric local man who doesn’t know anything about agriculture at first. Anyway, the great thing about Minari, as in the case of other films competing for Best Picture, is that it offers non-professionals a platform; not only it presents the stories of some ordinary people, but it also has ordinary people that play these stories. Of course, the same thing could be said about Nomadland – both films operate with autobiographical elements (Minari is partly inspired by the life story of Korean-American director Lee Isaac Chang, while Nomadland takes the stories of real nomads and brings them together around a fictional protagonist), both favor a certain perspective on life, one in which the characters do not seek elevation, but an existence based on a mutual exchange between the individual and the environment. In Nomadland, it’s the encounters between people, where no farewell is forever, all nomads shall meet again, on the road or in another life. In Minari, there is a close connection with nature. Turning a barren land into a fertile one is a miracle in itself, but it’s also hard labor: you’ll hear the head of the family, Jacob (Steven Yeun), rather complaining about backaches or heatstroke. Another relevant similarity is that both Yeun and Frances McDormand, the protagonists of the two films, are Hollywood stars – the argument that Yeun is an immigrant actor does not make him less popular, and McDormand is McDormand: asked how she managed to turn a star into an ordinary person, Zhao said that McDormand wanted to retire anyway and become a nomad in turn. Also living in a caravan is the protagonist of Sound of Metal (played impeccably by Riz Ahmed), a carefree drummer who suddenly loses his hearing – it’s funny that three of the best movies in this category are about people who either lose their home or look for it elsewhere. Among them, Nomadland is of course the favorite – it has an exceptional festival run, it’s a film about octogenarian nomads who refuse to spend the rest of their lives in hospitals, but rather seek the exceptional in nature; last but not least, it’s about a generation hit by the crisis, which makes most of the non-iconic America.

The discussion about making a star play as a non-star could also go for Anthony Hopkins in The Father, but it’s a completely different discussion. Zeller’s film, an adaptation of the play of the same name, is about an old man with dementia. The Father is closely related to the structure of the play, so everything takes place inside an apartment, with some ellipses/reruns of events that become more and more disconcerting, more and more difficult to put together; the bias is that the viewer witnesses the subjective perspective of the old man, which is fragmented-confusing. There are characters that enter the frame and then simply disappear, objects that change their place, characters that look different from one scene to another, in tune with the mess in the old man’s head. This is not necessarily a formula that works at full speed in cinema, although I understand the effect a theater play with the same dynamics could have. Still, Hopkins and Olivia Colman might have a good chance of winning in the actors’ categories, which is to be expected, even though Hopkins is not necessarily believable as a grumpy-stubborn old man and it was difficult for me to perceive him as the opposite of his gentle persona: it’s undoubtedly a star who plays impeccably an ordinary old man who drowns all his charisma with all sorts of vitriolic words thrown at those who care for him.

I don’t know if there have ever been two films in close relation competing for Best Picture, I may have missed them, but Judas and the Black Messiah and The Trial of the Chicago 7 talk about two episodes of revolutionary suppression (the first is about the persona of Fred Hampton, the leader of the Black Panthers, and the second, about the riots against the Vietnam War), both leaving a mark in the US history. More than just being brothers in theme, both films openly discuss police abuse against people of color – in the aftermath of the death of George Floyd, the victim of racism by a white police officer, the films come as a complement to an entire history of abuse by authorities – it’s sad and alarming that, decades later, the situation is just as complicated. The nominations also come with some historical controversy: LaKeith Stanfield and Daniel Kaluuya, both lead characters in Judas & the Black Messiah, could have easily competed in the lead actor category (although, if we take it the Christian way, the Messiah is always the protagonist, right?), but the Academy decided to nominate both of them for Best Supporting Actor. The anomaly is simply offensive – not to mention inexplicable: it seems that the white cop orchestrating Fred Hampton’s annihilation is actually the real protagonist of the film. It’s one of the reasons the Oscars have been boycotted as promoters of racism/classism, and you’d think things are starting to change over time, especially with the restructuring of voting body – I’m glad foreign films are on the radar of these awards – but it’s outrageous that there can’t be equity all the way.

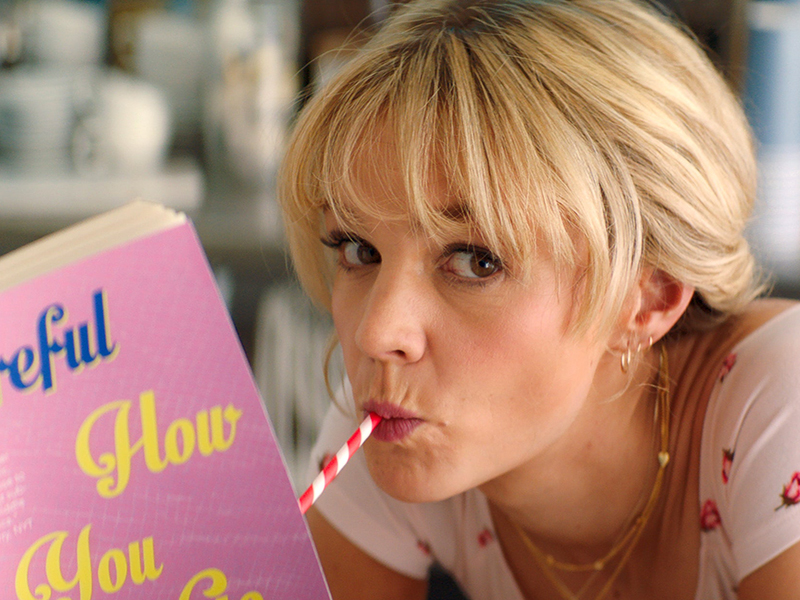

Last but not least, a film that makes history this year is Promising Young Woman, from so many points of view: it’s a film about a woman whose political acts are beyond relevant for our time: by day, she’s a lady dressed in pastels, but without all the fluffines included (Mulligan’s mature looks doesn’t really add up to this candy pink environment she lives in), by night, she’s a predator who lures men, pretending to be plastered, and they keep offering to “help” her. When the farce is complete, that is, when it’s clear that men only want to abuse her physical weakness, she “wakes up”, giving them hell, maybe that will teach them a lesson. Fennell’s feminist drama is my Oscar favorite, alongside Nomadland, because it doesn’t avoid cynicism – it exposes all this macho culture of lack of consent, and how society actually determines whether a woman has a right to be respected or not, through all sorts of discriminatory factors: if she’s showing too much legs, if she had one too many, if she’s chatty, and so on. The protagonist’s vendetta initially feels like a cathartic act for any woman who has ever been harassed, be it just verbally – but by the end it’s just an illusion, because it shows that all the activism carried by just one person is really water under the bridge if it’s not further spread. Thus, an award for this film would mean a lot in terms of visibility, but this is just a fleeting fantasy.

The Oscars have both the quality and the flaw of being predictable sometimes and extremely surprising at other times. Let’s not forget the almost subversive moment when the La La Land team rejoiced on stage for winning the grand prize, so that a minute later it all turned to be an error caused by a wrong note. There’s room for surprises even here, I only hope that all will be in favor of the films that haven’t already received (too much of) international recognition.

Journalist and film critic, with a master's degree in film critics. Collaborates with Scena9, Acoperișul de Sticlă, FILM and FILM Menu magazines. For Films in Frame, she brings the monthly top of films and writes the monthly editorial Panorama, published on a Thursday. In her spare time, she retires in the woods where she pictures other possible lives and flying foxes.