Footnotes: “We’re just like brothers” – a discreet life in pink

A boy is waiting for a girl; and how else could it be? The girl, however – who is a character in Dan Pița’s debut short film, An Usual Afternoon (1968) – leaves the young railway worker (played by Florin Zamfirescu) hanging, after the boy had done everything in his power to show her his meager crowded hotel room, whose coziness he’s been trying to improve. He dresses up, then undresses, then dresses up again, he improvizes a table; he prepares a bottle of champagne; a little bit of food; flowers; all for naught. Or is it? No, it’s just one of his colleagues, coming over to lend a hand in preparing for the big night – an extra pillow; a much-needed second glass; a smirk undercutting the preparations. Returning to his lonely existence, the railway worker indulges himself into the anxious gestures of waiting, which we know all too well from the hundreds upon hundreds of female characters we’ve seen before, as they sat in anticipation. Amongst these gestures, an extremely beautiful shot has Zamfirescu caressing a curtain. And when things finally become clear, who else to share his champagne with than his earlier friend? The problem is that the guy has already gone to bed, one that he’s sharing with another railway worker. The night couldn’t pass from the hands of the presumptive lady to the hands of the buddy. However, the next day, he will be snacking on the breadsticks that Zamfirescu had prepared for her; the switch has finally occurred.

Why am I saying all this? It’s because – improbable as it may sound – I seem to have found a little homoerotic spark in the few films that Dan Pița directed between 1968 and 1985, that is, during the communist regime’s fullest swing. I’d first caught on to it in Pas de deux (1985), where a few scenes that feature boxing matches and one dance scene caught my eye; a dance was also what stayed with me after I had seen Like a Wedding, the second half of Mircea Veroiu & Dan Pița’s 1973 Stone Wedding. The confirmation, however, came once I saw two of his schooltime short films from ’68 and ’70, both of them featured in UNATC’s priceless Active Archive (Arhiva activă) programme.

Of course, this doesn’t mean that I’m trying to turn Dan Pița into this unsung hero of Romanian queer culture; it’s more than safe to assume that any intention to suggest homoeroticism was not even crossing his mind, as he was shooting his films.

We know far too well that there was only a single way for Romanian directors to make films that would explicitly feature plots with homosexual protagonists – and that is, emigration, which is precisely what Radu Gabrea did before directing A Man Like Eva (1984), his fabulous chronicle of Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s life, cut short just two years before the film came out. Other than that, there was no other way for such work of the Devil to come onto our screens; devil work which, lest we forget, was criminalized at the time. Well, Dan Pița made it, somehow, managing to finalize a couple of films that are, at best, ambiguous in this regard. A Usual Afternoon raises a few questions. Why are we always jumping to the conclusion that a boy is waiting on a girl? And waiting to do what, precisely? Worst case, when the film’s economy is austere towards its female characters, who become but simple décor, they are expected upon just as a means to validate their partners’ heterosexuality in the eyes of the audience. Pița, however, chooses not to do so, but he doesn’t ground the state of affairs in his films in any other way either. From what we can see, we can easily imagine that this hotel is a hotspot for railway workers, meaning young men. The feminine guest could well turn out to be an intruder, in fact; even so, the spell isn’t relinquished. It’s the spell of men living in the absence of women, of those hotbeds of homoeroticism, “cultural myths which may be construed as exclusively male”, as photographer Hal Fischer calls them in his Gay Semiotics (NFS Press, USA, 1978); football players, swimmers, just about any athlete that relies on a locker room, roommates, best friends (“bros”), inmates, scouts, cowboys, soldiers, monks, seamen and so on. And now, railway workers. The thing is, once boyishness, camaraderie, the lyricism of male youth, or, in short, the homosocial context appears, Pița takes things a bit further than one might first expect him to do.

“The ejaculatory force of the eye.” (Robert Bresson)

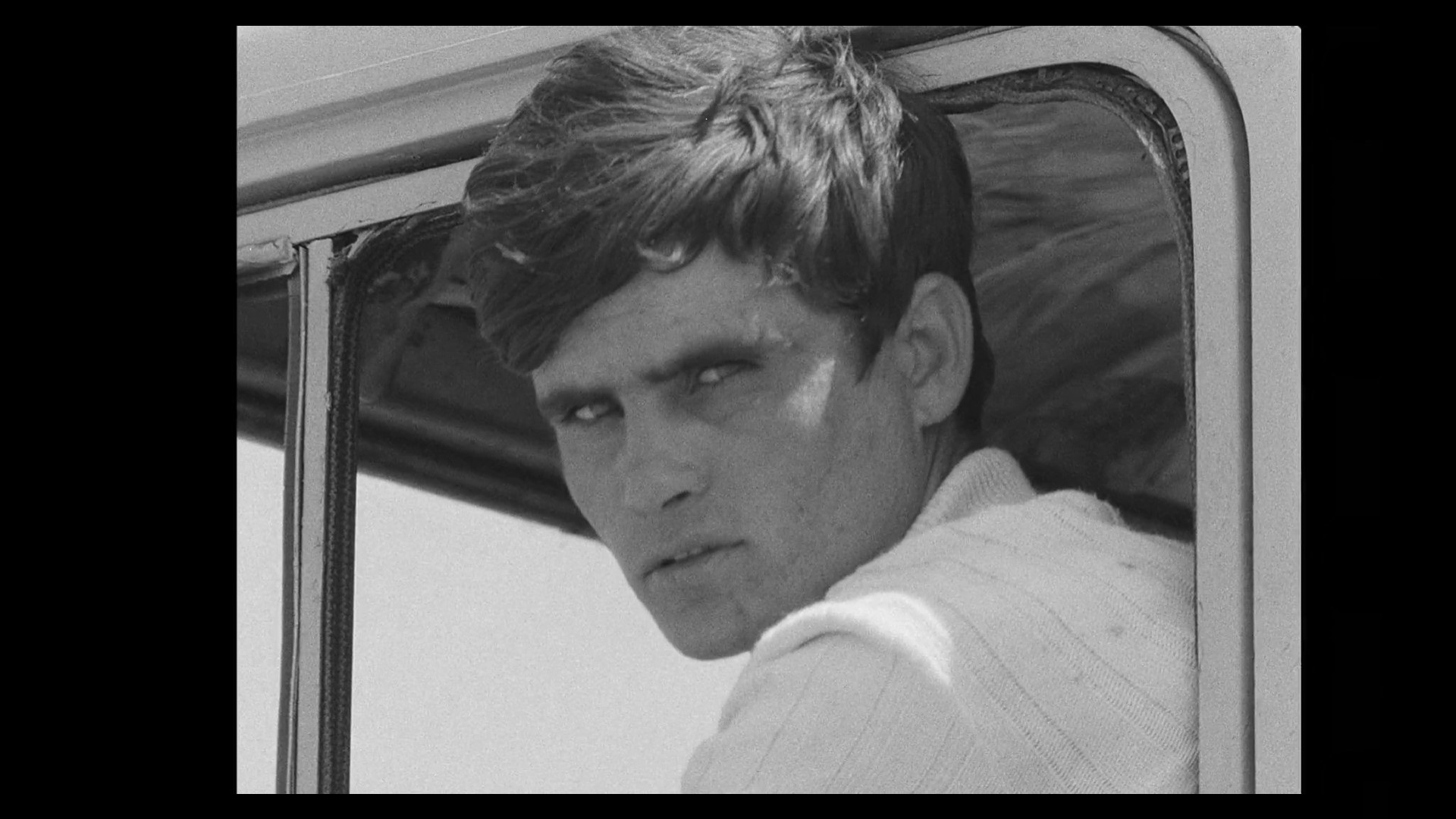

And Life in Pink (1970; since I did mention titles that tickle my fancy), yet another one of his student shots, goes even a longer way. A kid tries to wake his way through a series of excavators strewn across the edge of a lake, eating away at its corners; as it is, a day in which one goes swimming also entails the presence of a handful of boys in bathing trunks. It’s just that, amongst all of the boys, the one whom we accompany in the beginning is the target of the obstinate and deserted gaze of a truck driver; a strange fellow, young yet mature, dressed in a white turtleneck and perfectly groomed, amid a hot summer day spent on some muddy terrain. Both of them go down the same road, the boy on his bicycle, the worker in his car, but this is not where the film is supposed to end. The game has just begun; a game teasing, profoundly erotic and grave, lying at the limits between playing catch and surveillance. As the bicycle rider edges ahead on a forest path, the other catches up with him, taking a shortcut and waiting for his arrival, just as in a game of hide and seek. The two seem to willfully bump into each other as often as possible, and words are meaningless – they share none throughout the entire film. It just seems to be a game that is played according to a different set of rules, or that one of the two doesn’t seem to fully grasp what is going on; the boy is the playful one, picking up flowers and catching butterflies, while the eyes of the driver are steeped in what seems to be an appetite for violence. Up to a certain point, when something truly violent actually transpires; and from that point onwards, the two play the same game. They trip themselves up with glances, increasingly intimate interactions: a bicycle abandoned in the middle of the road, a fallen tree trunk, shot in a detail which makes it appear phallic, a football team that is in full training mode (and again, more pairs of shorts), and so forth, until…. – the boy dies after being hit by a truck, a different driver behind the wheel. While our driver sets his sights on another young man, another bicyclist; for each man kills the thing he loves. since we all end up killing that which we love. I realize that what Pița tried to achieve here is a poem written by four pairs of hands, with an urban colonizer and a rustic one; innocence and experience. Which makes it all the more generous in the context of a homoerotic interpretation, should one translate innocence as homophilia and experience as that particular urban and decadent form of homosexuality that was pejoratively dubbed queer (meaning dubious, pederast), which was later on reclaimed by activist movements.

Pița’s student shorts are not just case studies that are more or less evocative of what his intentions are towards excavating their potentials. These are films that are simply majestic, self-sufficient, crucial rearview mirrors for those such as me, who do not have the same enthusiasm towards Pița’s latter decades of work, nor that of Nicolae Mărgineanu, the then-young cinematographer of both films. Of course, this kind of interpretations have little to no place once one takes a look at Stone Wedding, Pița and Veroiu’s glorious feature-length debut, whose fame is alive to this very day; I, for my part, take the film as it is, and that is, a masterpiece worthy of its name.

Now that we’ve arrived at this point, things seem to shift in his medium-length Like a Wedding – women are now part of the game, and so lust is no longer negotiable. Isn’t it, though? A defecting soldier (Mircea Diaconu) stumbles upon an unexpected chance in his path – a musician, performed by Radu Boruzescu, who is traveling to a wedding where he’s supposed to play. And so, the deserter becomes a drummer and sticks to his alibi, should an angry mob come his way. The world into which they arrive, that of the Austro-Hungarian era small landowning farmers, one where people observe traditional rituals and wear chitchats, is constructed fabulously by Pița, however, this is beyond the scope of this piece. I am interested in the sudden brotherhood that develops between the soldier and the singer, so strong that Diaconu even sets his neck on the line for Boruzescu. That is because the protagonist of the wedding is an unhappy bride (Ursula Nussbächer) – a fact which is known since before the event itself, as the villagers gossip about it. Well, it’s clear that the husband can also see this, as she’s throwing glances towards the musician, glances which Boruzescu returns. One fateful day, someone should really pen an essay about how much importance Pița places on the act of exchanging glances in his films. Reality itself is nothing at all; a lustful look has the power to turn it upside down. Alas, this is where Diaconu intervenes, who, in the midst of increasingly insistent glancing, covers himself with the bride’s veil and sings her a little traditional tune:

“All the young girls that play

Under the walnut tree, they go and lay.

I alone no longer play,

No longer under the walnut tree do I lay,

Waiting at home, my beau,

Is forbidding me to go…

(…)

But to the garden I am not banned,

Where I go, holding another’s hand,

Behind the home’s wall’o brick,

Hiding in the forest, oh so… thick…”

Distracting the others, the soldier keeps on balladeering while the other two sneak out. The husband-to-be notices their eloping, however, and in short time, a handful of men are scouring the surroundings. The bride has betrayed, the musician likewise. They are nowhere to be found; the only one within reach is Diaconu, the fugitive singer’s closest next-of-kin, and significantly so, he’s the one wearing the veil, who was prancing about when the bride was still there, singing in the first person about unfaithfulness. He takes the hit out of camaraderie, but his comrade is Boruzescu, not Ursula Nussbächer; in her case, something strange seems to have transpired, something of hers seems to have transpired onto Diaconu, the one who manages to get away, who gets the chance to die as himself, before ending up dying as they do.

Another duo. A he, a fencing swordsman, and the other, a boxer; in fact, both are engineers. They tease each other in the gym, in a montage that fakes a confrontation – the youngest of them, Mihai (Claudiu Bleonț), has fallen for a girl. The other, considerably older than his counterpart, one Ghiță performed by Petre Nicolae, reminds him that he has vowed to finish his college studies before getting married (since the girl, whose name is Monica, and is played by Anda Onesa, seems to dream of having “a house, a family and children”); Mihai can’t help but remind him of his past transgressions, all of them surrounding women. “Am I ugly?”, asks Ghiță, sorely. “You’re not ugly, but you have no clue as to what poetry means”, Mihai retorts, his back resting against the punching bag, waiting for the other’s swipes. And then comes a close shot; the young man’s face, his fringe getting into his eyes, sweating in abundance, a crown of thorns of sorts on the top of his head. And the instructions – “Down, down! Left, right!”. Later on in the film, his dorm mates play a prank on Ghiță, and gift him with a puppet dressed as a bride. Ghiță promptly hangs it on top of the punching bag.

Let’s skip the little joke at the discotheque when two boys fighting over a girl are sabotaged by a third, who takes one of them to dance in order to free up the other guy. As well as the moment in which Ghiță and Mihai are singing a song about the beauty of love together. And even past the marching band rehearsals, while dressed in briefs.

And so let’s go back to our homosocial parameters; best friends ever since their army days, working in the same place, sleeping in the same room, both engineers at a factory where, on top of everything, women seem to be separated from men. But one could say that the plot of Pas de deux is largely set into motion by women. By Monica, of course, but especially by Maria (Ecaterina Nazare), a coworker and their common love interest. Mihai goes forward with both girls despite the risk, at first an unconscious one, to lose his friendship, his brotherhood with Ghiță.

“In your place? Me, I couldn’t be in your place.”

“That’s because you can only be Ghiță.”

But what or who exactly is Ghiță? A blue-collar laborer, yet a skilled one, a momma’s boy, from whom he learned a protective sort of respect for women (which is undercut by the others’ “locker room talk”), the proud owner of a Saviour complex, and in any case, a man struggling with stage fright. Whenever he’s in the situation of speaking up, especially at the factory team meetings, the man simply gets stuck. But, afterward, when no one else is around, Ghiță gets into the shower fully clothed, spitting out everything that he would have wanted his colleagues to hear, from beginning to end; something happens to him when everyone is listening, and there are things that one cannot say out loud. The shower scheme, in spite of being based on hot water, brings to mind that little trick that men pull in order to avoid having an orgasm, throwing cold water onto their nether parts. It’s fair enough to wonder why Ghiță insists that Mihai remain a bachelor for a few more years. And why is he so eager to leave his bachelorhood behind? There is a sequence towards the end of the film where Mihai sits down on the staircase leading up to his dorm, at an equal distance from Maria and Monica, both shocked by the revelation they’ve just had. Well, Ghiță is sort of the same: he’s practically insisting for Mihai to stay back with him, after all, while the other placed himself at the whims of Maria, wanting to quickly get things over with – a home, a marriage, a family, and just about everything that would validate his heterosexuality. It’s precisely then that Mihai’s “we’re just like brothers” becomes convenient to him.

A husband is waiting for his wife; and how else could it be?

Film curator, writer and editor, member of the selection committees of BIEFF and Woche der Kritik, FIPRESCI member and alumnus of the film criticism workshops organized by the Sarajevo, Warsaw and Locarno film festivals. Teaches a course on film criticism and analysis at UNATC. He has curated programs for Cinemateca Română, Short Waves, V-F-X Ljubljana, Trieste Film Festival, as well as the Bucharest retrospective of Il Cinema Ritrovato on Tour in 2024 and 2025.