The Vloggers‘ Cinematic Universe – from 5GANG: Another Kind of Christmas to Teambuilding

For some it’s heresy, for others it’s a form of liberation: just like in the case of all past important moments in Romanian cinema, the Romanian vlogger film genre defines itself in contrast to precedents. Cinemas are once again brimming with people because the audience is finally being offered something else. Altogether, the 4 most important vlogger films have amassed over 1,8 million spectators (only for the moment – the time of writing is November 2022, and Teambuilding is still running in cinemas). Romanian films are becoming profitable once again, and the revolution was not televised, because it was online from the very beginning.

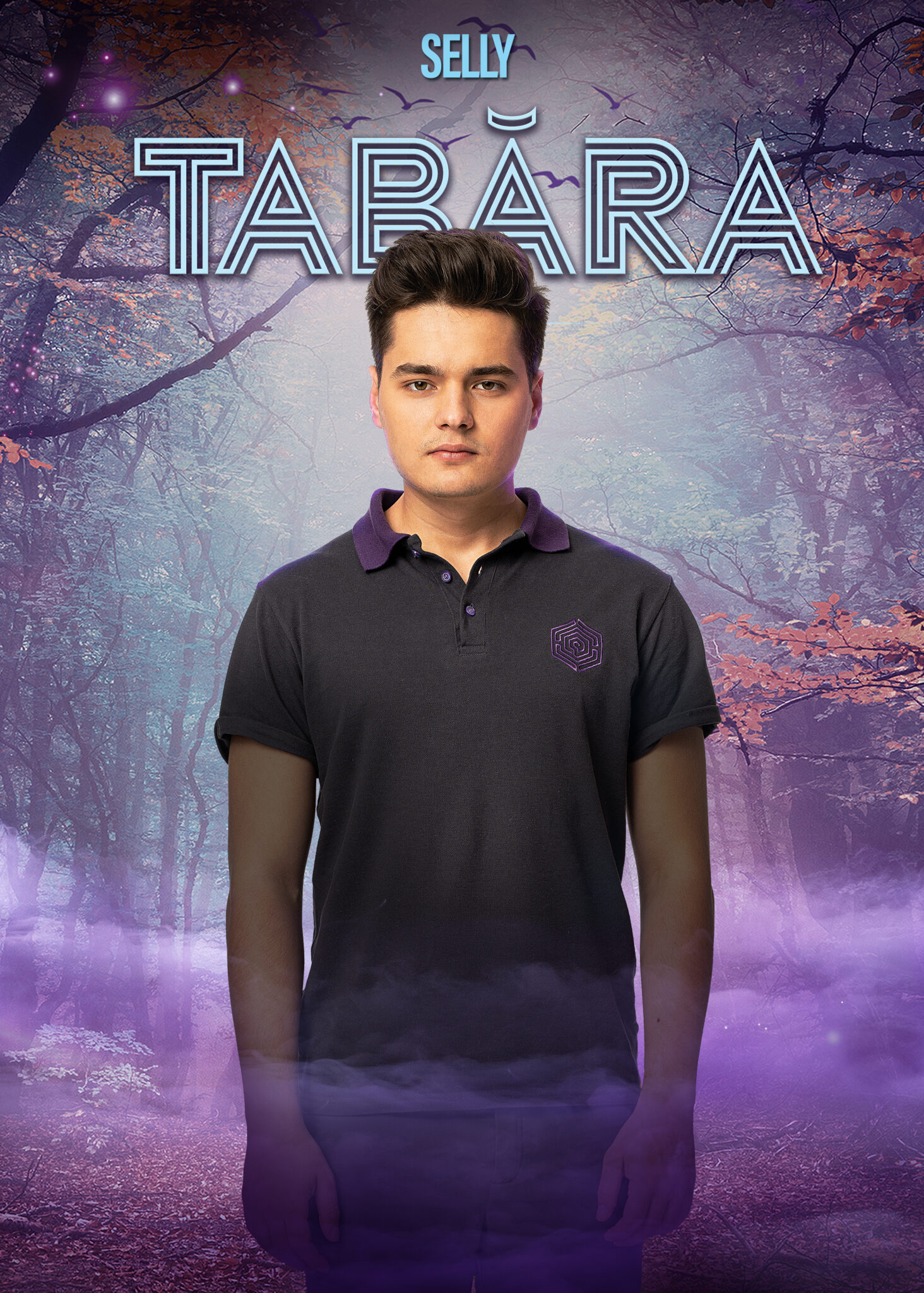

No matter the title, the sensation is the same. You didn’t see The Camp, starring Andrei Șelaru as the lead actor (or Miami Bici, or 5GANG: Another Kind of Christmas, or Teambuilding): what you saw was Selly the Vlogger walking from one frame to another that simply happens to be The Camp – which might very well have been titled One Hell of a Night or The Olympiad, and the plot could’ve been set in a bar in central Bucharest or on a ski slope. The scripts are seemingly written based on a brief, one that describes their brand identity in minute detail. Predictably enough, for the number of spectators to rival their follower counts, the characters performed by the vloggers in these films are as close as they can be to the image that they’re projecting of themselves. And so, Matei Dima’s characters are treated in a fashion that is radically different from Selly’s, in 5GANG and The Camp. If he wouldn’t be a jokester, BRomania (Dima’s persona) would be nothing at all. While, on the contrary, Andrei Șelaru (Selly) takes his role as an opinion leader much more seriously. Of course, Selly is also capable of making fun of himself, but never so emphatically as to avoid landing on his feet. His image is a monolith.

The script for Miami Bici (2020) was penned by Codin Maticiuc himself, the actor who performed one of the two lead roles, together with comedian, Alex Coteț. In the film’s first act, the two – who are fed up with living the humble life – become increasingly involved in the fiber of a mob gang, a bad decision that they take with smiles on their faces, and whose consequences they soon start to face. In the third act, the two lose their hardly-gained status, but at least they manage to save their hides. There’s nothing left of their initial naivete, but that isn’t to say that we’ve just witnessed a character arc. Beyond (and above) these narrative patterns, Miami Bici is the sum of several gags, which are thought and carried out just like in TikTok videos.

During the title credits (but not limited to them), we see traveling shots of Miami taken from every imaginable angle, an indelible mark of the confetti-cinema practiced by Spanish filmmaker Jesús del Cerro. Our first encounter with this couple of protagonists also marks the first usage of a quid-pro-quo, which is constructed through the use of framing: sitting in a car, the two sniff something that is not visible, under the deck of the car. A few seconds later, it turns out that they were snorting the garlic sauce that was supposed to pair with their shawarmas. At the end of the scene, yet another new perspective: Ilie and Ion are not the owners of the black Mercedes, but rather, the employees of a car washing business.

Adrian Silișteanu’s camera offers plenty of such moments, some of them ingenious. In the first shot, Ilie forcefully utters a declaration of love; in the second, the camera frames a hamster. The Albanian (i.e., the character who might be brokering Ilie and Ion’s departure) is on the phone with them, and what we can’t yet see is that in the same room, between the legs of the Albanian (Florin Piersic Jr.) lies Sorana (Letiția Vlădescu), Ion’s partner. And so on. Long prepared, the revelations of these two-shot gags are more often than not rushed: Maticiuc and Coteț are always racing towards their next gag.

At the end of their workday, Ilie and Ion discuss the possibility of emigration. A joke about the Albanian is followed by two jokes built in the same pattern, coming one after the other. Miami and New York are included in the same enumeration as Amsterdam and Berlin so that in the next sentence, it follows that the four destinations are representative of the whole of America. Not a minute goes by and psoriasis is lumped in together with chicken pox, scarlet fever, and arugula, all of which are nuisances whose path to becoming a disease could be prevented by a vaccine. When the two finally visit the Albanian, he’s in the middle of a discussion that seems to be about mob executions but is really just an ordinary pizza order. Miami Bici has something that recalls the communist-era black-and-white national television skits, where innocent identity confusions have been replaced by adult fun and mobishness, and moments of maximum hoo-hah are provided by word-for-word translations of thick swear words, or their usage as-is, by Ion, Ilie, or the film’s other characters, generally foreigners.

There is no shortage of color and homophobia, both equally shrill. Ion’s grandmother thinks that Ilie is a “fag”. Ion never misses an opportunity to assert his heterosexuality. Nevertheless, when the prospect of arrest looms over them, he points out to Ilie that he is a “pussy”, so incarceration is not an option that he might embrace. Finally, Ion and Ilie take great pleasure in whipping Fabio on Svetlana’s orders, and their pleasure seems to derive from the fact that they perceive him as a deviant (not for nothing, but they call him “that freak”). No surprise here: in Miami Bici, success is synonymous with a pool full of female bodies, whose main occupations seem to be bathing and frolicking.

The Camp (written and directed by Vali Dobrogeanu, and released in 2021) proposes a different style of humor. Much more of a recording of a roast than a comedy, the film is also based on lightning-speed gags, but that calls for the involvement of two characters. The first one says a random line, while the second one rapidly turns it into an insult. „This dude is missing his mother again.“ / „I don’t, but I will give your mom a call, ’cause she’s definitely missing me.“ „I am trained in the dark arts“ / „I can see that you’re quite dim.“ „I was hiding myself“ / „Well, you’re a little too big for that.“ „Can you believe that my girlfriend doesn’t like Crispy Strips?“ / „Oh my god, you have a girlfriend?!“ And so on. Even so, the film doesn’t lack its fair share of situations or lines that play into a larger endgame. A good example would be the scene where Rafael (David Dobrincu) seems perfectly convinced that Nadia (Hu Nadd) will be more sensitive to his charms after meeting his mother, who is the camp’s resident psychologist (and who, it turns out in the end, has hypnotized most of the camp’s participants). Selly is more than the star of the film. Character-Selly also bears the activism of vlogger-Selly. As a direct consequence, he forces people to respect each other’s personal space, advocates for non-aggressive educational methods, and even calls for the empowerment of new opinion leaders. Cezara is on the opposite side of the spectrum, in terms of how she relates to the ethics of being a content creator („Other people’s kids are not my problem. I have an unsubscribe button, like every other channel. Whoever doesn’t like what I’m doing can simply not watch it“). The policemen – performed by none other than Dobrogeanu and Matei Dima, once more in his role as a destructive dunce – also have the function of putting Selly under the spotlight. And, finally, Dorian Popa pops up when he’s least expected, and his role is to be a destructive brute (in contrast to the always-rational Selly).

If The Camp proposes two-voice distiches as a form of comic resource, in Teambuilding (2022), the humor is almost entirely dependent on editing and language. A line like „it’s sliding in perfectly!“, heard from a hotel room after a night of excess, is not about some form of penetration or another, but about a morning yoga session (in other words, the frame doesn’t extend like in Miami Bici, but rather, it changes entirely). Another example of a quick, thus hyper-precautious comedic procedure: in a given shot, x, a given thing happens – an intention is made clear, or a bit of plot is foreshadowed. Let’s say that it’s a character that swears to never drink alcohol anytime soon. Almost invariably, in shot number x+1, the promise – no matter its contents – is broken (and so, we see the aforementioned character slip into an alcohol-induced coma). Teambuilding might not offer much in terms of suspense, but it certainly has loads of surprises.

In terms of language, the scriptwriter of Teambuilding is twice unqualified. Alex Coteț seems overjoyed at the thought of making his characters swear in the most colorful ways possible in the Romanian language. Occasionally, organs are gift-wrapped, a dissonant linguistic supplement, because it derives from business-type terminology. From his past experience as a corporate worker, Coteț has extracted several certainties and a superiority complex, rather than insights. His use of jargon is primitive, an approximation of corporate lingo. In the parallel Romania of Teambuilding, southerners are drunkards, Moldova is only populated by the female half, and Transylvanians speak softly, with an intensely-mockable accent. The final weapon in the arsenal of so-called funny filmmakers like Coteț, Dima, and Cosmin Nedelcu: the de-glamourization of slow-motion shots. Most often men, often corpulent, often drunk, moving around in slow-mo. Doesn’t seem much? It’s still more than nothing.

The gags in 5GANG: Another Kind of Christmas (2019) show Selly in the same position as a leader, with a touch of exasperation. The star’s patience is heavily tested by his crewmates, who irresponsibly squander the band’s resources, but also by the members of a local mob, who ask him to perform a private show, only for them to kidnap him afterward. In one of these situations, humor results from how the shot is framed: in the foreground, Selly rolls his eyes, while in the background, his mates are being roughed up by the bodyguards at the entrance of a club. Depth of field, where one least expects it Despite the exasperation brought on by his entourage, Selly still chooses to sacrifice himself on the altar of the greater good, which allows for a type of situational humor that is more or less convincing. Of all the films that feature Dima and Selly, 5GANG is by far the one that looks the most like an advertisement of a product – that is, the vlogger performing in the lead role -, and if the comedic elements are rare, that is also because of the difficulties of targeting an audience who is more often than not underaged. Selly takes a dumbfounded look at Cristina when she tells him, in slow-mo, that his fly is open: desexualization or an infantile take on the meet-cute trope is perfectly representative of this film’s target audience.

To draw the line, the main constant of this vlogger cinematic universe is the usage of short-ranged humor, which eliminates the risk of jokes missing their intended targets. However limited the audiences‘ capacity to keep focused may be, it’s unlikely that any of these back-and-forths buried within the dialogue or the editing style of Dima and Selly’s films will pass by unnoticed. From a narrative point of view, the protagonists are always entering an adversarial terrain. The characters are extracted from within their native environments and catapulted into an entirely unknown reality. The villa of a mobster, a camp in the woods, a villa in Miami, a villa in the mountains. A different world, with different rules, which, consequently, means that any sort of transgression is justified: drugs, sex, brawling (with someone in particular, or in a generalized fashion). They don’t throw whipped cream at each other, but rather entire plates of food (in The Camp), respectively, punches and kicks (in Miami Bici and Teambuilding). Another target, that is less young, looking for different thrills. No matter the context, there will always be product placement within the film. Kaufland, the Transilvania Bank, a restaurant called Trickshot and Campofrio in The Camp. A palinka brand called Dom’ Profesor in Miami Bici. BMW and Savier Medical in 5GANG. Napolact, Stradale, Tazz, Aquavia, Hygienum, Vlad Casino (amongst many others) in Teambuilding. And what about women? They manipulate men by using their charms (Raluca from 5GANG), abusing their power (Svetlana from Miami Bici and Alinuța from Tabăra), or cunning (The Camp), whenever they are not outright fawning and opportunistic (like the HR boss in Teambuilding).

All of these four films explore or at least tick off a series of socio-political topics. Miami Bici gives a couple of hints (about the climate, which makes Ion and Ilie flee the country) and espouses a series of grand platitudes (it’s all the same abroad). Teambuilding defines the corporate employee as a sort of hamster, that is aimlessly running on a different kind of wheel. The Camp opens up a discussion about vloggers‘ responsibilities towards their followers, while self-complacently introducing the concept of free will into the discussion. In 5GANG, the importance of setting limits in parenting is emphatically discussed, while the effects of global warming are discussed in passing.

Finally, we have two radically different ways in which the author relates to his characters, the irreverent/bashful (in BRomania’s films) and commendatory (in Selly’s films). Whilst Dima’s entire career is that of a surfer riding a wave of cringe, who always swims back to the surface because, after all, he has a stable basis, Selly has something of the aura of a judge or a referee. He is the one who establishes what is cringe, and what isn’t. More to the point, he is the one who defines cringe, because Selly is the very definition of coolness, at least to his faithful audience, which is not necessarily cinephile, and not necessarily of adult age. Without some form of idolatry, vlogger comedies would be impossible.

Film reviewer since 2009, artistic director of "Divan" Fil Festival (2017 - 2018), and HipTrip Travel Film Festival (2016 - 2018). Winner of the 2012 Alex Leo Șerban scholarship (TIFF), in 2016 of the competition "Be a film reviewer at Cannes" (Les Films de Cannes à Bucarest). He was published in "Politicile filmului" and “Filmul tranziţiei”.