The World According to Alexander N.

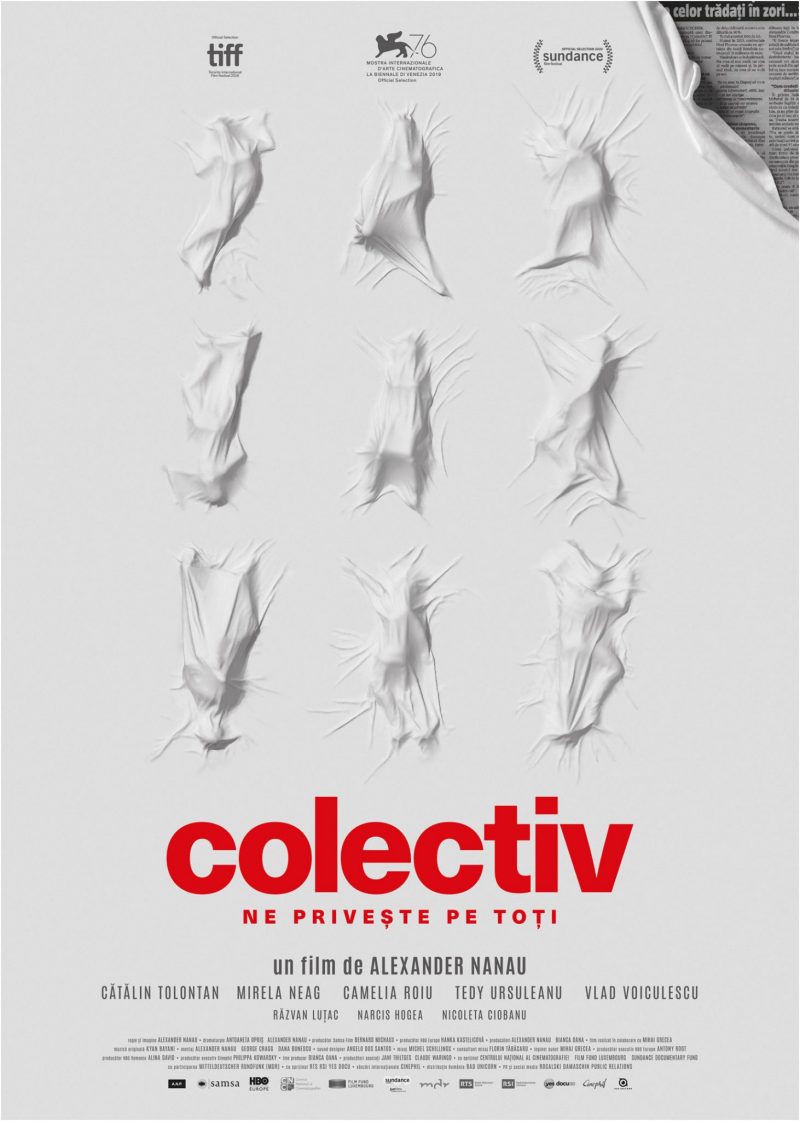

Alexander Nanau is the man of the hour. Collective has just been nominated for both Best Documentary Feature and Best International Feature Film at the 93rd Oscars.

Maybe the presidential administration should insist on giving him a medal? Earlier this year, Nanau was at the center of a small cultural-political scandal, after refusing the president’s decoration – in protest over failing to look after the cultural sector during the pandemic. I hadn’t seen Collective at the time, so I only made a note of the political response which came as absurdly aggressive. After watching the film, the proposal itself seemed preposterous. Pandemic or not, the director’s decision should’ve been obvious from the very existence of this film. Obvious for anyone who knows how to “read” a film. And you can accomplish that even with less than „7 years of formal education, 16 months in the army and 3 months in prison. Followed by the `school of life`”, as Ion Barladeanu (the protagonist of another documentary by Alexander Nanau) would say. If those involved in the decision really watched the film, then they missed the whole point. How is it possible for you, the Romanian government, to think that it’s a good idea to award a film that gets its recognition from showing the failure of the state?

But this kind of professional ignorance (bureaucratic at its core, let’s reward what others have rewarded first) made me think about the perception of Collective as art, and of Nanau as an artist. Caught between a stellar festival circuit and a subject that triggered the greatest collective emotion since the 1989 Revolution, there is a risk that the director, in terms of his profession, may be brought to his knees. Otherwise, the director (as a person) enjoys the huge success of his film, but most of the interviews fail to escape the gravitational pull of the Colectiv phenomenon (following the tragedy of the club fire) to bring into focus the film itself. Everyone agrees that it’s an important film, that the director did a great job, but no one considers why this is the case. With Nanau’s preference for the observational documentary proving to be an advantage, there’s a tacit agreement that we made the Oscars due to the Colectiv event, not thanks to Alexander Nanau. If we add the fact that half of the film has a politician as a hero, meant in both ways depending on which side you are on, the film is either truth or propaganda. But is it art? This article sets off in search of the author, using a collage of images and red threads that cross the three films by Alexander Nanau to outline his profile.

Nanau didn’t make three, but four films

The fourth is actually his debut, shot in Germany: Peter Zadek inszeniert Peer Gynt, an observational documentary that follows the process of adapting a classic text by Ibsen into a theater play, by one of the greatest German theater directors (Peter Zadek directs Peer Gynt). Born in 1979 into a Saxon family, Nanau emigrated to Germany immediately after the Revolution. He studied at the German Film and Television Academy Berlin, made his debut with the film about Peter Zadek’s staging of the play, and since then, he has been making films focusing on Romanian realities. I haven’t seen his first documentary, but this synopsis backs up my first impression – in fact an admiring rhetorical question – from watching Toto and His Sisters: how the hell do you end up filming in the privacy of an apartment in the Ferentari ghetto, full of heroin addicts, while injecting in their neck veins? Before having intimate access to the world of Toto, Ion B. and, why not, Vlad V., the director practiced the art of observation without disturbing in a much more volatile and sensitive environment, at outsiders: the creative dialogue between the director and the actors in search of a play. I don’t know how good Nanau’s “German” film is, but with only three Romanian films, the director easily becomes one of our top documentary filmmakers (after ’89).

The outcasts

“I don’t understand what you want with this man (…) What to expect from a drunkard who, 24/7, can’t even remember his own name? / He is a great artist.” These are lines from a dialogue captured by Nanau between gallery owner Dan Popescu (the one who discovered and promoted Ion Barladeanu) and a neighbor conflicted by the interest of some intellectuals for a somewhat homeless man. Of all the directors who “disgrace us” and win awards by showing the misery instead of the attractions of our homeland, Nanau (given his dual citizenship that makes him even more suspicious) should perhaps be among the most discussed. It should be so, indeed, because the documentary film (unfortunately) doesn’t arouse so much interest; and if it were otherwise, then perhaps there would be less zeal and a greater dialogue.

This obsession with the way we present ourselves to the world is a little bizarre. After all, the first non-fiction images we debuted in the free world are the televised revolution and the execution of our former leaders. Then, we reinforced our brand of shocking cinema with images of horrors in orphanages. At that time, Alexander Nanau had just emigrated to Germany. Something made him come back and persevere in making films here.

The World According to Ion B. is about a homeless man, with an amazing talent in the art of collage and a collection just as great. Toto and His Sisters revolves around a family – three children, their mother in jail – but the generous way it follows its main characters reveals an entire community of poverty and addiction. Nanau makes films about people on the outskirts of society and, his latest, about an entire society on the outskirts of society. It’s probably harder to realize this thing – because the Colectiv tragedy has sparked a national consensus, and because the film is perceived rather as investigative journalism that exposes high-level corruption – but Collective shows quite clearly a situation just as clogged and foul-smelling as the garbage chute that Ion Barladeanu keeps unclogging.

Fly on the wall

In order to have enough material to work with – even more so in the observational documentary – you first need inside access, you have to be accepted. This kind of trust also depends on the director’s talent. Either you get it through a greater personal involvement, as seems to have been the case on The World According to Ion B. – a film that also caused a fairly consistent scandal in the cultural bubble of the Capital (the full history of the relationship between the character and its two benefactors, the gallery owner and the director, can be read here). Or you are validated by a character with authority and prestige in the community, as happened on Toto and His Sisters. The film was born as a project financed by European funds, developed by Valeriu Nicolae’s NGO. But Nanau gets the credit on managing to turn such a project into a film and not educational material; and it’s Valeriu Nicolae’s doing when it comes to keeping all the doors open so that the camera could sneak inside without any trouble.

With Collective, at least when it comes to the journalistic half (real-time access to Tolontan & Co.’s investigations), what Nanau had previously succeeded to do with very delicate subjects also mattered, most probably. As for the political half, if we were to look at it objectively, Nanau’s access to the highest level of the Ministry of Health was a win-win situation. Leaving aside the director’s attraction to the character of Vlad Voiculescu, it is clear that the former (and current) minister knows how to look great on camera. His reformist discourse featured this important component of transparency “in order to regain someone’s trust, you have to stop lying to them”, he states slightly nervous at the first press conference. Transparency comes with PR, and there’s nothing wrong with that. That doesn’t mean it’s an elaborate front for something (you can also check out the accusations related to the film’s release during the election campaign). Voiculescu has a native talent for presentability, and he’s not at his first documentary that presents him in a good way (see The Network, Claudiu Mitcu’s documentary).

The camera is unforgiving

There is a sequence in The World According to Ion B. in which the artist is called to the gallery to sign his works – a savvy move in terms of making profit, since a signed work comes with guarantees of authenticity, and thus can be sold for a higher price. Nanau records in turn the faces of the two, the poor artist and the capitalist who takes advantage (or so it seems like). The handheld camera lingers on the grin of the latter, looking almost like a cartoon. It’s like you can see him rubbing his palms together, with the dollar sign stuck to his retina. I don’t know if that was really the case (there was a whole scandal on the profits’ split and the relationship between the three of them), but the fact is that Nanau has this ability to essentialize portraits. He does so by using different type of shots, camera movement, shot length, composition, but always but always based on the character has to offer. Moreover, The World According to Ion B. works at a micro level and as an excellent index of the “once upon a time” kind of neighbors.

As for Collective, one can not forget Minister Achimas Cadariu clenching his jaw. Surrounded by journalists, he displays a robotic grin as he presses menacingly on every word: “they are the only ones accredited to do that”. He eventually relaxes, after he is saved by the bell: “Would you rather had us bring some aliens, dear sir?” The next minister, Vlad Voiculescu, has no such problems, he is almost a superstar when it comes to the relationship with the media. An American publication for film writing and criticism even rewarded him with an “unexpected heartthrob award”: “the youthful Minister proves a charismatic companion, not devastatingly handsome, mind you, but appealingly suave in a rimless-glasses, substitute-teacher way (you notice some flirty, appreciative smiles from the press corps).” I included the whole argument because it illustrates a critical distance somewhat harder to grasp by the Romanian public, given the subject. I actually think that Nanau giving so much attention to Vlad Voiculescu – for which he was rightly criticised – is also related to the director’s honest interest in this charismatic character (and, in some way, maybe even the desire of Nanau, as a citizen, to support a political figure and a decision making process that are not afraid of an open mic). On the other hand, the camera doesn’t spare Vlad Voiculescu either, although it’s more difficult to make the connections: a minister being driven in a limo so he can vote in his village, has just about the same effect, regardless of the political color. Much less revealing than the wars fought by Tolontan and his team, Voiculescu’s battles are rather media wars (defensive ones though) and damage control actions.

How personal does it get?

One can notice that in recent years, during which Romanian documentary has gained considerable ground, the trend is to turn the camera more inwards. For example, Andrei Dascalescu‘s latest film, or two of last year’s debuts, directed by Andra Tarara and Tudor Platon, respectively.

Alexander Nanau’s approach is somewhat different. The camera is set as far away as possible, but things become personal in the process. It may not always come as clear, at least not in an obvious way, as is the case with The World According to Ion B., the only documentary in which the director is physically present (we can hear his voice from offscreen). For the most part, it is the director’s voice that wants to find out things from the character (“The World According to Ion B.” is not a full observational documentary). However, there is this one time when the director simply intervenes to advise his character that he might ruin his boots on the eve of the opening. In an interview, Nanau stated that the first thing that drew him to Ion Barladeanu was his resemblance to his grandfather, to whom he dedicated the film. He also came up with the idea of taking Barladeanu to his family in Vaslui, out of the desire to explore this event in the film, but also as a personal involvement in the emotional balance of the character.

As for Toto and His Sisters, it’s interesting to see how Nanau’s very presence there may have hijacked the children’s lives in a better direction (as Andrei Gorzo argues very well here). Beyond just being present, Nanau gets involved out of an artistic impulse: he offers one of the sisters a video camera to keep some sort of diary. On the one hand, it has to do with the creative process and the way in which Nanau adapts his observational approach to the subject. For Nanau’s film, the material filmed by Andreea would practically fall into the category of found footage. But apart from the director’s wider strategy, the teenager creates her own film, where her brothers are the actors (and many of the most emotional moments are shot by them entirely).

Collective is the film where, theoretically speaking, the director’s personal involvement should be diluted by the exhaustive gaze upon a society in transformation: we have the journalists’ story, the minister’s story and the stories of the survivors. There’s a lot of noise and anger, a lot of characters, teeming newsrooms, TVs that announce breaking news by the minute, street protests. But all this transformation, which at the time of filming no one knew where it would lead, was introduced by Nanau through a stylistically coherent, aesthetically satisfying directorial decision, but it was also a way to show that it’s personal. After the footage from the fire, grief sets in and speeches sprout at every corner: the prime minister, the minister of health, and so on. The voices are easy to recognize, but Nanau practically denies their existence, refuses to put a face to the political leadership and shows only a black screen.

Empty words, useless paperwork

Collective – before actually watching it – provided me with a key to pay close attention to a particular type of dissonance between reality and rules. A dissonance that Nanau’s camera manages to capture very well and that (literally) explodes from the first minute of his first Romanian film.

The World According to Ion B. begins with the protagonist lying on a mattress behind the apartment building where he looks after the garbage chute; behind him, in the background, garbage bags, thrown from above, crash on the cement. One can feel the pedantry in this scene, but the sequence is memorable and comical. Romania is the country where things may fall on your head. But what really got me thinking was the relation between rules and reality. There are, of course, countless reasons why people would throw their garbage on the window: the garbage chute is clogged, some trash bags are too big and don’t fit the chute, and so on. Nanau’s camera doesn’t judge, but somehow shows the inadequacy. There is a garbage chute, a solution to a problem, this is the rule/requirement, and it’s complied with. The inadequacy is not that people use the more convenient solution of simply throwing their trash on the window, but that they still use the chute alternatively.

Sometimes hilarious, sometimes ridiculous, the camera records the futility of procedures, the over-regulation, and the need for bureaucracy to bury themselves in papers. In Toto and His Sisters, a mother convicted of drug trafficking arrives before the parole board. After a monologue arguing that “she didn’t try hard enough to integrate into society”, the woman is asked to sign the report, in two copies. Nanau has the camera on the character all the time, while the remarks can be heard from off, some more rigid (the pretentious expressions read from the document), some more common (platitudes like “it’s up to you to leave the penitentiary”). The close-up is used in such a way that only when she signs the document the viewer can see that they kept her standing all this time. In another sequence, one of the sisters receives an “intensive course” in bureaucracy after refusing to use her father’s name: “Whenever you fill out an application, and there are lines intended for info on mother and father, you have to write their names.”

Collective is practically a long series of such moments in which empty formulas and smooth appearances come into conflict with warped realities. “We have absolutely all the conditions to provide maximum care to the European standard.” No one in Europe would make reference to a European standard. The moment you are in Europe and you have to mention that, it’s pretty clear that you don’t measure up to the standards. A futile attempt are also the donations of biocidal products after the Colectiv fire, made by Hexi Pharma – the very firm that was selling hospitals useless disinfectants is donating them now. And the tests on these biocides are conducted by ICECHIM: “the only institute in the country specialized in such tests, yet not accredited”. Beyond the moral, criminal aspects, the image that these details build is of a society in which the substance and the form are determined on living apart. Sometimes it even happens on the better side of the barricade. At a meeting between journalists and representatives of the medical system, the camera captures the courtesy appetizers on the table: the questions and answers on the inadequacy of the system in response to the Colectiv situation, nosocomial infections and major burn victims, cross paths over these platters with pâtés and pain au chocolat.

Of course, all these things exist even in the absence of Nanau, but the camera records differently depending on who’s standing behind it. Being a fly on the wall means more than just pressing the REC button. And to complete the circle, here is the state’s reaction to Nanau’s initial refusal: “When they called me again to give them an answer, I told them that I didn’t want this medal in times of crisis, when culture is on the brink of collapse. And they requested I give them a written answer.”

With this double Oscar nomination, Alexander Nanau writes history for Romanian cinema, that after already writing it on several occasions (at a much smaller scale, indeed): world premiere at the Venice film Festival, an award by the European Film Academy, a BAFTA nomination (chances increase after the double stunt at the Oscars). Even without a pandemic, it would have been quite difficult to explain to the general public how important the steps taken by Nanau with Collective are. There’s a certain weight, and especially visibility, to making it to the Oscars. The impact it has goes beyond Nanau’s career (it will certainly be much easier for him to make films from now on), and it should, in theory, have some beneficial effects for film production in Romania and its distribution across the ocean (but either way, the impact far exceeds the “promotion support” provided by the Romanian government). And if he does win at least one Oscar, who knows, maybe Alexander Nanau will even trigger a small moment similar to the “Simona Halep” phenomenon, and will inspire a generation of children to grab a camera and start filming. Like he did with Toto’s sister. Hers is the first name that appears on the film’s credits, immediately after that of the director: “with sequences filmed by – Andreea Violeta Petre”.

I will conclude the portrait of the author with a scene from Toto and His Sisters, which shows at a micro level the sensitivity and intuition of the documentary filmmaker for the moments that deserve to be “observed”, the kind of filmmaking that gets you to the Oscars. At the same time, it confirms something that Nanau often insists on in interviews: the importance of having an eye for casting, a vision of the potential. It also shows the talent of making yourself invisible, the perseverance to remain the one who “turns off the light” after the last drug addicts have left the house, and the skill of setting the camera in a spot that turns simple recording into a story. Heroin users have just left the apartment, Uncle Sile is floating in another world, and Toto is pouring water into a kettle. “Do you want, Sile, egg boiled?” There is something incredibly touching in this erroneous inversion used by the unschooled boy and in the genuine concern for his uncle, the adult who should take care of him instead. But Uncle Sile is far away. The “fly” on the wall is now moving on the ceiling. All alone in the world, a 10-year-old boy boils a single egg, perfectly centered, in a kettle with chipped enamel, on an improvised heater made of a wire embedded in the AAC blocks. “Sile?”

Film critic and journalist, UNATC graduate. Andrei Sendrea wrote for LiterNet, Gândul, FILM and Film Menu, and worked as an editor on the "Ca-n Filme" TV Show. In his free time, he works on his collection of movie stills, which he organizes into idiosyncratic categories. At Films in Frame, he writes the Watercooler Wednesdays column - the monthly top of TV shows/series.