3 Visionary Filmmakers in the World of Images

Meet some of the most acclaimed emerging filmmakers of the moment. Employing a combination of unconventional visual means and narrative techniques – from archives, and video-essays to social media materials – their films have an innovative approach towards the conventions of cinematic language.

***

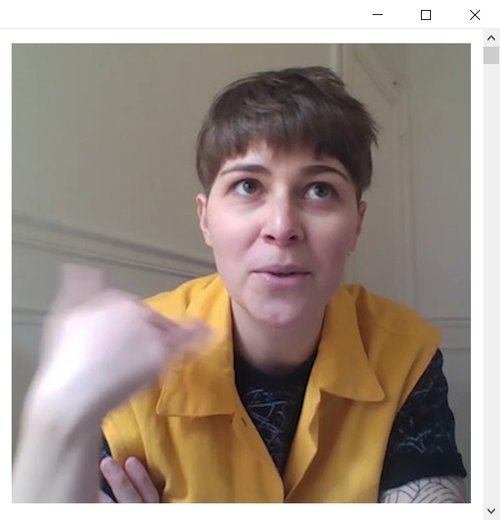

Chloé Galibert-Laîné and the testimonies of the Web

Over the past few decades, the visionary filmmaker Harun Farocki imposed the image of the artisan who looks over images with a style of curiosity that owes just as much to theory as it does to practice. Both essayist and laboratory worker, critic and curator, Farocki turned his editing table into a sort of center of the universe: always available to “receive”, he answered the increasingly abundant image flows of the West, offering us various keys to watching them. Not necessarily a sort of Brechtianism that would get us suspended in a state of distrust towards images, as much as it was a true, pedagogical vein meant to constantly clean up our relationship to the audiovisual.

Farocki’s brilliant intuitions have created an informal school of thought, reunited under the ever more cramped umbrella of essay films and video essays. But few can lay claim to having prolonged his heritage more faithfully than Chloé Galibert-Laîné. “Faithfully” not in the sense of lackluster epigonism, but of affinities towards the audiovisual heterogeneity of the present, of similar concerns towards the ever-changing ontological status of images, between manipulation and judicial evidence. The supple nature of both accumulates observations that may be culled from all across the territory – from pop culture to Vilem Flusser or Serge Daney, to the same degree to which it reflects an all-encompassing intelligence, that is all-around valid. Since just as Farocki’s investigations led him to the Nazi camp in Westerbork (Respite, 2006) to the aesthetics of video games (Serious Games I-IV, 2009-2010), Chloé Galibert-Laîné may also speak to us, within the bounds of a single film, about the Boston Bombings, a film by John Carpenter and a whole load of clips and vlogs found on YouTube (Forensickness, 2020).

After all, this oeuvre radicalizes Farocki’s wager: a pioneer of the so-called desktop documentary, Galibert-Laîné transforms the screen of a desktop computer into a window to the world itself. Adeptly leading us between icons and tabs, they turns the layers of the digital interface into an electronic landscape of sorts in which split screens, video-text superimpositions, and various websites become the panoramas, super-impressions, and location sets of old. With the arrow of their mouse acting as a guide, the filmmaker introduces us to a world without a backstage, in which montage is a constituent part of the image, and the image itself becomes its own object of study.

The material of these works is the very audiovisual fabric of our existence. As such, the possibilities are infinite. In what is likely her most important achievement, the Bottled Songs series (co-directed together with iconic video-essayist Kevin B. Lee), Galibert-Laîné studies the audiovisual production of the Islamic State, mobilizing tools specific to cinematic analysis, a voyeurism that is typical to digital natives and a fascination that is not at all unlike that of classical cinephilia, to track down a fanatic young man whose luminous face left a troubling mark on her. The result is a formidable investigation into the rotten innards of the Web, which reads as a thriller about the current age of images, one that is as problematic as can be. From this “market of gazes”, Galibert-Laîné is capable of extracting a testimony about the contradictory position of the

Internet user, this anonymous individual who turns his laptop into the pretext for a journey that goes far beyond the virtual, in an epic reshuffle of usual ways of existence. (Victor Morozov)

***

The Light Images of Nicolaas Schmidt

Cinema knows that time means light: shootings are organized in way that allows the sun to be kind to them. And still, filmmakers have rarely used light as an object and subject to the same degree to which they used time – and if they indeed do so, then few noticed it. Here, at last, is Nicolaas Schmidt, whose films are precisely plays of light, or rather, plays of twilight – the so-called “golden hour” –, the double moment, of utmost importance, that lies in the immediacy of both sunrise and sunset: anything that happens in this diffuse light comes seems holy, decisive, since it’s the beginning ot it all – or the very end.

Schmidt hasn’t made many films – even so, a couple more than what I’ve managed to see so far. I easily went through his First Time, his only medium-length film, at Locarno in 2021: back then, I wondered by the jury, of whom Adina Pintilie was also a member, awarded it, but I have understood in the meantime. Because it happens that Inflorescence – with a rose and, lost in the background, a German flag swaying in the wind for around seven minutes, while in the background, a slowed-down version of Don’t Dream It’s Over – won the award for Best Filmmaker at BIEFF in the same year. Again on the big screen, Schmidt’s cinema seemed to bear an incredible visual self-conscience: a gaze that is simultaneously longing and suspicious towards the (im)possible naivete of all contemporary images.

„To be consumed lightly”, the filmmaker writes, since his cinema plies itself to the aesthetics of comfort: young people with angelic, Netflix-esque visages, Coca Cola commercials, constant twilight, karaoke and pop music. Once comfortable, the spectator will feel the shocking paradox of alienation brought upon by the extreme banality, of un-happening in Schmidt’s cinema: for the most part (that is, 40 out of its 50 minutes), First Time is a long single shot in which two unknown boys timidly share glances without having the courage to take the first step. The view beyond the window, which crosses tunnels, landscapes and lights, becomes the film’s major subject, while the spectators’ anxiety only grows and grows – briefly before moving into the train, a montage of Coca-Cola advertisements with uplifting mottos flashes on the screen. It’s quite clear that Schmidt’s boys are not only not having an uplifting experience, but are moreso embodying a contemporary neurosis of the masses: the impossibility of becoming a protagonist, the futility of striving for the close-up shot that a protagonist culture promises at every step.

A few years ago, the same actors performed in another one of his short films, Final Stage (2017), a de-dramatized melodrama about a boy that gets angry at his boyfriend and cries all throughout a mall in Hamburg, the biggest in Europe, for the entire duration of an 11-minute-long single shot. Once more, the foreground is pointless, since the action happens in the background, amongst the shuffle of shopping bags, advertisements, restaurants that sell the traditional food of faraway, unknown lands: light images, anonymous, culturally naturalized to such a degree that they’re part of an unknown visual subconscious, one that, however, can be understood apriori – Schmidt’s view of this is clear, and his manner of showing it all the more so. (Călin Boto)

***

Gagman Nikita Lavretski

Nikita Lavretski is a very young filmmaker and media artist from Belarus who adopts Internet practices, uses video material gathered from the online environment, and always keeps the Internet in mind when he makes his films, even if it’s not in the foreground. Nikita Lavretski is playful, or, in the words of Cahiers du Cinéma, “The most interesting gagman of the invisible Belarusian scene!” Nikita Lavretski is also a very prolific filmmaker; in 2022 alone he released eight (!) no-budget films and media projects, which can be seen on his YouTube channel.

He uses forms of expression that are typical of the Internet and he explores – with much ease and fluency – the instruments provided by social media platforms. His films and video artworks are simultaneously timely and formally compelling, be it how he makes use of found footage, home movies, or the way that he shoots an entire film from a single shot on the camera of an iPhone. (A Date in Minsk, 2022), or war films that literally use TikToks and other vertical-format videos, that are “freshly picked” from the Internet.

But even in films that don’t directly refer to the Internet, one can sense its indirect influence. Perhaps his best-known film, Nikita Lavretski (2020) – a mixed media self-portrait – uses home videos and personal found footage (family recordings plus some material from his attempts to make a documentary as a teenager), spanning the journey from VHS to still-not-smart mobile phones when he was 16. The cross-referencing of recent media, the superimpositions of snapshots of himself as a child over sequences from Spider-Man – the Tobey Maguire one from 2002 (this childhood film of everyone younger than 35) – give his film a memetic quality and encapsulate a particular form of nostalgia that belongs to our generation of early zoomers.

Nikita Lavretski is politically involved. He speaks out whenever he has the chance – through his films, but not exclusively – about Russia’s violent and odious invasion of Ukraine. He made one of the world’s first films about it: Jokes About The War premiered in March 2022. The film overlays stand-up artist Alexey Suhanok’s TikToks with footage of bombings in Ukraine and war-affected cities, thus mimicking the inevitable alternation between the types of material that a social media platform’s newsfeed turns up.

Lavretski is relevant not only for his all-too-natural way of operating with forms of audiovisual originating on the Internet but also for the ease with which he embraces his formal approach and perpetuates his political beliefs. (Cristina Iliescu)

An article written by the magazine's team