A top of the best films of the year

My list is most likely an ultra-eclectic and personal lineup which only reflects my joy to watch slow cinema, horror, stylistic and thematic quirks. The order is not important – how could I rank them when Bacurau comes from Mars and The Irishman from Venus? Most of the films here had a sporadic presence in cinemas or film festivals in Romania or could be watched at home via Amazon Prime or Netflix. I didn’t leave TV series out, because watching the mini-series mentioned here is a cinematic experience without question.

- Too Old To Die Young (dir. Nicolas Winding Refn)

Nicolas Winding Refn’s new toy is so static and dead-pan that it often gives the impression of a glossy-gothic painting with a theme just as like – a policeman tries to investigate (and avenge at the same time) the death of his colleague, killed out of the blue by a Mexican cartel. In the end, the series is more about questioning the obsession and masochism of human nature; how far one’s fantasies on power can go, how much evil can be done in the name of good, and so on. If I were to choose only one title to sum up this year, Too Old to Die Young would probably be the one.

Too Old to Die Young can be watched on Amazon Prime.

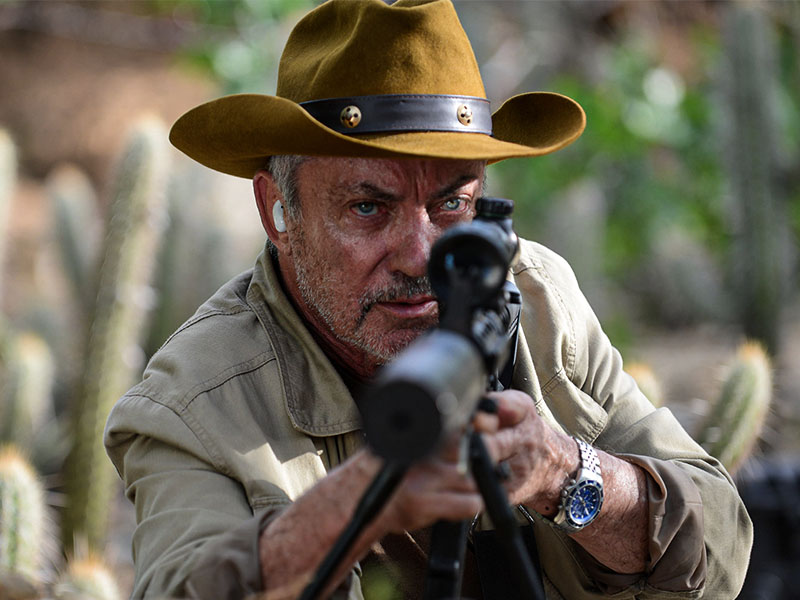

- Bacurau (dir. Kleber Mendonça Filho & Juliano Dornelles)

Bacurau is a dystopian man-hunt (neo-western, comedy, drama, political film, all at the same time?). In a village forgotten by the world (actually completely erased of Brazils’ map), a handful of American soldiers, driven by severe boredom, hunt the villagers with their high-tech gadgets and weapons. Only the villagers have their weapons, too – the fist and the thirst to destroy any form of oppression (be it political or any other kind). A cynical metaphor for colonialism: a flying saucer follows a man riding the most wrecked motorcycle. He looks up, he looks left and right, and he continues on his way.

Bacurau could be watched at Les Films de Cannes à Bucarest.

- A Hidden Life (dir. Terrence Malick)

In what way can Malick’s new movie be viewed as a return to an old style? Although generally perceived by critics in this way, A Hidden Life is merely an extension of Malick’s research over the last years: a film in which not the subject nor narrative logic are important, but the inner world of the characters. The protagonist, an Austrian soldier who loves and is loved, destroys the peace of his rural community because he doesn’t want to take an oath for Hitler. His world from this point on is limited to the letters he writes to his wife, which eventually are returned to him – about life outside prison and between its walls. What Malick does here is pure poetry: the emotion-oriented editing combined with the pantheism of landscapes and lighting do more than the moral-religious dilemma of the film. The protagonist refuses to take the oath out of his conviction that he would betray God, that he would knowingly join the evil this way. How could he support something like that? He is not an activist, but a lonely wolf that doesn’t belong to any political group – he is all alone in his blind and stubborn faith.

A Hidden Life could be watched at Les Films de Cannes à Bucarest.

- Border (dir. Ali Abassi)

The underlying premise of Border is so wild, that it is incredibly inventive: Tina (Eva Melander), a Border Patrol officer, has a very developed sense of smell. Thanks to this ability, she can “smell” guilt – and thus, expose dealers, criminals etc. Her appearance is grotesque – a face that turns heads, as well as keeps people at a distance. Once she meets Vore, an individual who looks an awful lot like her, not only cannot smell him, she finds out that both of them are trolls, the mythical Nordic creatures who stole children as described in tales. Anyway, without being a complete spoiler, Border is a love story between two physically repulsive people, who cannot fully integrate into a society like ours – though Tina is perfectly functional, even cherished and appreciated by Swedes, she can’t escape her otherness.

Border could be watched in cinemas in Romania.

- The Irishman (dir. Martin Scorsese)

What The Irishman manages to emphasize, besides the unglamourous life of a senior gangster, is the very process of getting old: Robert de Niro, Joe Pesci, Al Pacino, are here a very serious trio of old people but not very believable at times: they can still pull a gun, but a one-on-one scuffle might make them pant. The digital reconstruction of their faces, undergoing a forced “rejuvenation” is first disturbing, then candid – a near-young face who commits crimes in an old body seems like a creepy paradox, as do more or less the artificial wigs on their heads. However, The Irishman is one of Scorsese’s most remarkable films – Sheeran (De Niro) remains the last gangster alive (is there a more cynical way for a mobster to die than old age?), but refuses to confess / tell anyone the truth about himself.

The Irishman can be watched on Netflix Romania.

- Synonymes (dir. Nadav Lapid)

About Synonymes I have written here before; the protagonist, Yoav (Tom Mercier), the man who walks through Paris, is a foreign traveler – only that, unlike a traveler like Jep Gambardella in La Grande Bellezza (dir. Paolo Sorrentino, 2013), Yoav is so uninterested in the glamor around him, that is perceived as melodramatic. Under the surface, the film is political-dramatic, but really funny – in one of my favorite sequences, Yoav arrives at a pretentious party in downtown Paris, but he is starving. He is slinking left and right between the bodies of the dancers, and at the end, when he succeeds in reaching a plate of food, he lashes out on it.

Synonymes could be watched at Les Films de Cannes à Bucarest and other festivals in our country.

- In Fabric (dir. Peter Strickland)

Although it’s labeled a horror movie, I would call In Fabric a splendid anti-capitalist parody: a cursed red dress (maybe even possessed) moves around the homes of its owners, destroys their washing machines and makes them fall into depression. The shop from which it comes, a fancy dump, where the sellers are gothic villains, holds prisoners in an eternal elevator, a Sisyphean system where tailors of all kinds weave the same dress to infinity – what better metaphor for the limits of capitalism? Bonus: one of the “fashion” victims confesses at one point that she has been on the pages of the fashion catalog, and while the store’s sizes were increasing exponentially, her body was getting slimmer, until it looked like a skeleton.

- Happy as Lazzaro / Lazzaro Felice (dir. Alice Rohrwacher)

A review of Happy as Lazzaro written by me can be found here – a film about politics like a wave that swallows you and carries you on unexpected paths, about a rebirth in a grim capitalism etc. It’s cynical that Lazarus resurrects in a world that no longer needs miracles, because he can no longer recognize them.

Happy as Lazzaro has screened in our cinemas.

- Maniac, Netflix

Probably the least high-brow presence in my top is a mini-series created by Cary Joji Fukunaga (True Detective, Beasts of No Nation etc) which starts from Don Quixote and gets to Celine et Julie Vont en Bateau (dir. Jacques Rivette): several individuals with mental problems are guinea pigs for some kind of drug therapy, thus fantasy is encouraged. But the intricate and animated world in the characters’ drug trips has nothing to do with the desolate and empty reality around them; fantasy comes to replace it. It’s one of the few films that treat mental illness not as a potential clock bomb, but with empathy and courage.

Maniac can be watched on Netflix.

- La Flor (dir. Mariano Llinas)

With an impressive length (808 minutes, set in 6 episodes), with four actresses playing several roles (and thus changing from main characters to extras), Llinas’s experiment is worth more than a paragraph, so I’ll only say this: it starts from genre films, reinterprets them, gives them a meta-cinema meaning, plays with time and space and, despite the apparent solemnity (a feature we usually credit to such long films), La Flor is completely the opposite.

Journalist and film critic, with a master's degree in film critics. Collaborates with Scena9, Acoperișul de Sticlă, FILM and FILM Menu magazines. For Films in Frame, she brings the monthly top of films and writes the monthly editorial Panorama, published on a Thursday. In her spare time, she retires in the woods where she pictures other possible lives and flying foxes.