Godard. „I was this man who roamed paradise in a dream”

We were all used to knowing him among us, plucked now and then from his cold Swiss remoteness to once more give the exact time to the world. In recent years, his sporadic appearances had become more and more surprising: a masterclass via Zoom, at an obscure festival on a strange meridian, a live on Instagram, a short video for the premiere of his last film at Cannes. Jean-Luc Godard passed away at the beginning of September and left us as he lived: always one step ahead.

Godard – where to begin? One needs to figure out a new, “Godardian” way to tell the story of this child of the century, who ended up exemplarily embodying its light and contradictions. He crossed through the history of cinema, starting from its very beginnings, letting himself pervaded by its flow to the same extent he generated it, in a remarkable one-to-one ratio. He gave himself the entire past, a scholar who became his own object of study, a gravedigger working on his own death. He himself looked at his growing shadow and played with it solemnly and playfully, sometimes profound — “I was this man who roamed paradise in a dream” — other times wisecracking, and perhaps it would not hurt to call him, at least now, “uncle Jeannot”, as he appears in Prénom Carmen (1983), comically attached to a tape recorder, inappropriate and already worn out. For the role, of course – but how much was premonition, how much self-irony, and how much flair for the spirit of the times?

Godard loved to laugh at himself – especially when those around him saw him as unapproachable and sulky, an increasingly lunatic old man who held the last key to the universe in his pocket and was waiting to turn off the light. In Romania, as in other parts, there are eulogies, overly polished pictures, circumstantial lines, all the same. Even a radio show described him, a poor cliche always at hand, as “one of the most important representatives of the Nouvelle Vague”. Oddly enough, an exceptional oeuvre whose discovery, here, in Romania, came to a definitive halt when, really, it seems as if it had not even started. The hypocrisy of the “professionals of the profession” (his very words), very prompt in laying the bouquet of flowers out of a sense of duty at the base of an imaginary statue, with no connection whatsoever to the model. Which is not to say that Godard’s ’60s films – those that made it not only into the canon but also into the common language of culture: from his debut À bout de souffle (1960) to Weekend (1967), going through Le Mépris (1963) and Pierrot le Fou (1965) – should in any way be dismissed: on the contrary, along with a few other exceptions (Jean Renoir’s ’30s films, Rossellini’s post-war films), they constitute, I believe, the proof of the early genius of this creator. One masterpiece after another, titles that changed the face of cinema forever, some so beautiful – others overwhelmingly beautiful –, like Le Mépris, that revisiting them might do us more harm than good.

But Godard, for those who saw these films as something more than some clever gimmicks that heralded postmodernism, carried on with his work. In fact, he did so for a long time, in his own style: with disruptions. There are several chapters in his career, just as there is a common place, which states that, regardless of the position he assumed, Godard remained a film critic all the way to the end – which is also how he started, somewhere in the ’50s, under the pseudonym Hans Lucas, spreading thoughts worth reading (hint: they are extremely precious) in Cahiers du cinema. Which, like everything he touched in life, became over the years the scene of a misconception, living in popular culture as “the magazine where the Nouvelle Vague directors made their debut”: a stiff quip sold at the newsstands, but read too little.

Beyond the opportunist ignorants eager to catch the right train/trend, there is another community, smaller but steadfast, which rallied to Godard’s death, turning social media into a mass vigil. Cinephiles, those for whom Godard really meant something, left aside the usual cliques, aware that, in a way, our man has been a key reference junction, and that any polemic, any renegotiation, any update must start from him. Our passion, often too sectarian, too quick to exclude, always found a point of reconciliation and calm around Godard, whom many have been willing to consider, without exaggeration, the greatest filmmaker of all time. It’s difficult to describe to an outsider how significant this figure is to anyone who claims to work with images: first, because it doesn’t seem translatable into the language of other arts (it’s a mythology more akin to sports gods, I believe); then, because it is based on a variety of grounds, beyond the catchy lure that is the Nouvelle Vague, which traverses the history of media, technology, aesthetics; and finally, because although Godard seems to have imposed upon us, cinephiles, a dominance never brought into question, it took the form of an unexpectedly intimate, personal relationship with each one. The filmmaker’s filmography is simply so rich – like a labyrinth you can get lost in as you please – that describing its appeal is less of an analysis and more of a confession.

Godard was a free man — free to abandon narrative in favor of essay films, free to abandon stars in favor of quotations and collages, but also free to abandon nuance in favor of momentary certainties, circumstantial blindness, groundless challenges, as researcher Georges Didi-Huberman shows in one of the best works on the subject, Passés cités par JLG. But none of the filmmaker’s active periods has been unfruitful, not even the early ’70s, when, together with Jean-Pierre Gorin, he launched into close combat with the theorist demon, from which he emerged how else than defeated, but also willing to get a clean slate and start over, in the name of an unshakable conviction in the image. Supposedly, the ’70s and ’80s are the least fertile of his career. I believe they had, first of all, the misfortune to be the least looked upon, out of an instinctive fear of any defiance of the norm, be it towards the ideological antagonism, the video format experiments, or the obscure references. Passionate, Godard dove into his projects with seriousness and rigorousness, a fact so misconstrued in Le Redoutable (2017), Michel Hazanavicius’s childish mockery: a logical contradiction where the critical portrait of the filmmaker is accompanied by the stylistic effects he popularized over time (text cards, red-white-blue chromatics, etc.), though emptied of any subversive power and reduced to sad gags. “Being slandered by a mediocre man/ is precisely the proof of my perfection,” as poet Al-Motanabi once said (picked from director Abbas Fahdel’s Facebook page).

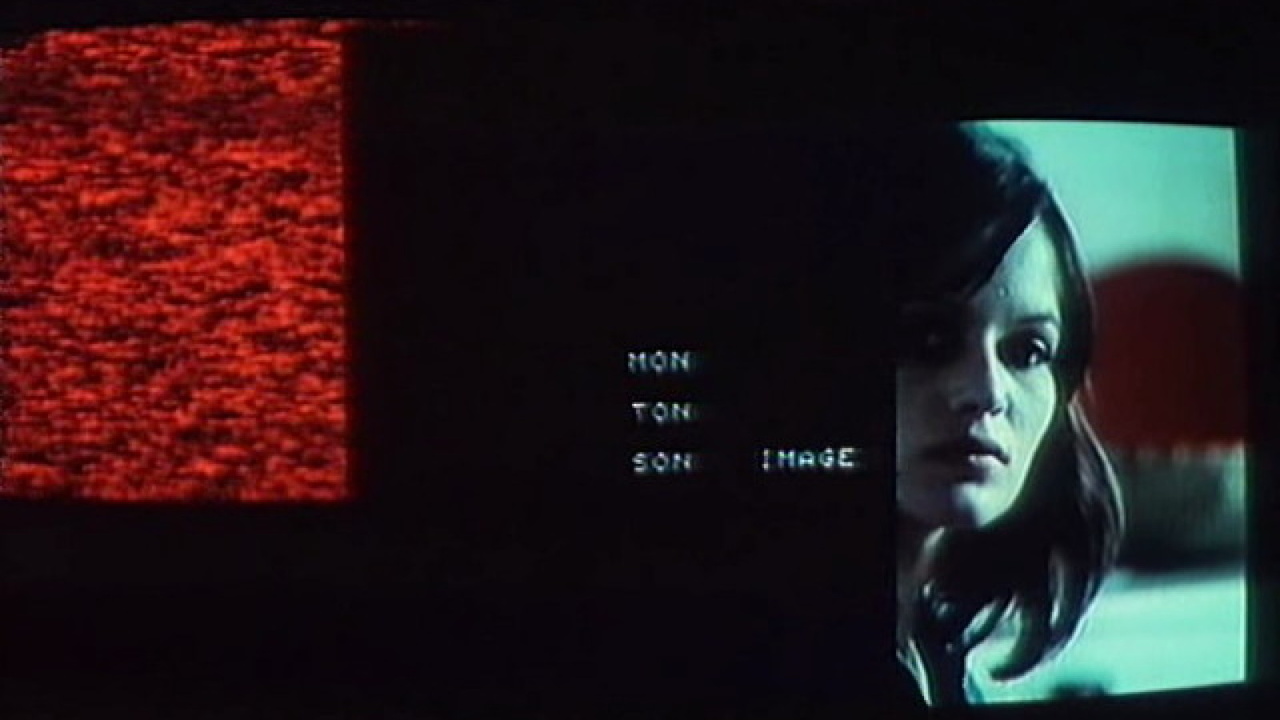

On Le Mépris, Godard had Fritz Lang – an old master of the silent era and of a classical Hollywood that was already on the decline by that time. On Numero Deux (1975), he shot, in split screen, two television monitors that conveyed a cross-criticism of bourgeois society. On Histoire(s) du cinema, since 1989, he edited frames depicting a century-long history of cinema. On Adieu au langage (2014), he shot in 3D. On Le Livre d’image (2018), his last film, he edited footage of the shores of Arabia and terrorist acts carried out by ISIS. It’s clear what has changed here: Godard’s position on the moving map of media, a gradual evolution towards its edges, aiming to uncover new paths in his search for legitimacy. It’s not about an “artistic program” here, because the filmmaker acted by intuition, quick flashes, and maximalist erudition, breaking the walls of stagnant cultural hierarchies. Godard is important not only because “he was cinema” – as film critic J. Hoberman rightly proclaimed – but because he showed, from the very core of cinema, that there is a life after/beside/outside it. We might even say that it’s thanks to Godard that the practice of cinema has become decentralized worldwide, happening both on a technical level (cheaper equipment) and on a content level (any image has earned the right to life on the big screen), since he was the one to expand the issue and turn it into an insoluble problem. One can also notice his choosing of more and more degraded materials in the conception of his films: from the worshipped artist, towards the related and plebeian media (television, video), to ending up in a direct confrontation with the Whole of image as it travels around today, in disarray. The importance of this massive upheaval of prejudice, when so many people around us choose to keep the door closed, preserving old hegemonic positions, cannot be underestimated.

In her film, À vendredi, Robinson (started in 2014 and finished only last year), director Mitra Farahani imagines a correspondence between two masters: Jean-Luc Godard and Ebrahim Golestan, one of the great Iranian filmmakers of the last century. The final result, however, does not live up to the intention: no real connection occurs between the two, but an abyss that neither appears able to cross to the other side. Golestan rather resembles a bourgeois and bitter old man, and Godard, a lot more humble in appearance, is too sophisticated (and solitary) in his associations of ideas: he must have sensed the danger of reverent celebration and avoided it as he knew best, through intertextual acting and perplexing paraphrases. The film turns out to be a failure, because the idea it conveys, most likely unintentionally, is a slightly ridiculous truism: that old age is not a very pleasant thing. But at least it concludes by leaving us in the company of one of the most beautiful images of Godard I’ve ever seen: a happy, smiling face of a man so at peace with himself that he has nothing more to add. From now on he can draw the line.

Film critic and journalist; writes regularly for Dilema Veche and Scena9. Doing a MA film theory programme in Paris.