Kicking off 2021: Four films to watch on Mubi

We leave behind a ruthless 2020, which all of a sudden messed up all of our plans in terms of cinema (and not only), thus becoming the year of series binging, online festivals and catching up with our long watchlist, which might be the worst nightmare of any moviegoer used to running between theaters in order to catch the next premiere. With the cinemas still closed or shyly opening their doors to the public, this period can only feel like being in hibernation or on standby, so I come up with four auteur films, all available on Mubi, which might make our back and forth in our apartments more optimistic, more adventurous – two of the films roam the streets of New York, one takes place on a psychedelic planet and the other in the ’70s Parisian bars and train stations.

Fantastic Planet (dir. René Laloux, 1973)

Fantastic Planet/La Planete Sauvage, probably the most trippy cut-out animation of the ’70s, is a France-Czechoslovakia co-production, an adaptation of the Stefan Wul’s 1957 novel, to which Roland Topor (Jodorowsky’s collaborator, btw) gave quite a surreal and visionary touch. The underlayer, however, is undeniably a political one: a planet dominated by Draags, a blue, totalitarian humanoid civilization with red eyes and advanced technology, which looks at the scattered civilization of Oms (the equivalent for humans, only that on this planet they are small, the size of ants) as a source of personal amusement, keeping them as slaves or pets, but nothing more. Tiwa, the daughter of a Draag governor, adopts an Om by mistake, raises him, teaches him French, but keeps him on a leash and never lets him free. Always forced to keep her company, Terr also attends her hyper-complicated lessons about civilization and science, aired through some giant headphones, and comes to possess the knowledge of the humanoids. Like any SF movie depicting the overthrow of power, Terr will reach his own kind and get them out of the cave, where they used to organize fights with sea creatures just for the fun of it, thus preventing the eradication of his own race. Why watch this movie in 2021? It’s a universe so visually cohesive and so complex beyond the screen that it doesn’t make it very clear for the viewer, it’s like a postcard behind a partially lit window. Where else could you see a landscape in which a carnivorous plant catches flying insects between its teeth, chews them up and then spits them on the ground, with an air of satisfaction?

P. S .: Fantastic Planet is one of the inspirations behind the contradictory universe in Raised by Wolves, Ridley Scott’s series – at least in portraying the war between humans and robots.

Duelle (dir. Jacques Rivette, 1976)

And on that magical note, Duelle, the 1976 film by Jacques Rivette, one of the directors of the French New Wave, was to be part of a series of four films entitled Scenes from a parallel life, based on a mass of idiosyncratic genres and mythologies about two goddesses, one ruled by the sun, the other ruled by the moon, each with her weaknesses, who spend 40 days on Earth, where they experience the terrestrial frivolities. From what was meant a four-film series, only Duelle and Noroît (1976) came out – if Duelle is a magical realism with noir nuances, Noroît is a musical with pirates – both use shooting on location, music as a diegetic and extradiegetic element, but also a set-up that feels quite artificial. Simply put, in Duelle, the long-delayed revelation of the fact that the two delicate beings who are in a constant search for a man are goddesses comes in second throughout the story, and each clash of forces arises in the middle of a discussion where the piano can be noticed in the background or is heard out of the picture; other than that, there are several dancing moments in which the extras come to a stop when the conversation between the protagonists ends, making it obvious that is just a farce. As in Celine and Julie Go Boating, Rivette builds a universe in which magic is embedded, but never fully revealed – the two goddesses duel in finding the magical diamond that would allow them to remain permanently on Earth, but they are always at the mercy of the mortals, so they cannot use their non-carnal powers, but only resort to the feminine weapons of seduction.

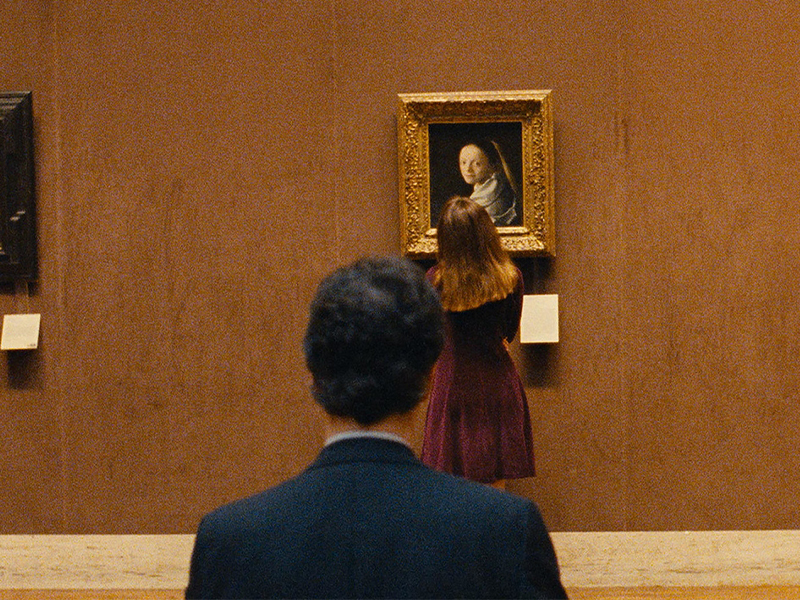

All The Vermeers in New York (dir. Jon Jost, 1990)

All The Vermeers in New York, Jost’s low-key romance, revolves around the 17th-century Danish artist Johannes Vermeer’s painting Study of a Young Woman. Mark, a stock-broker (Stephen Lack), and Anna, a French actress (Emmanuelle Chaulet, best known for Rohmer’s L’amie de mon amie), cross paths at the Met Museum. They keep lingering around the painting and eventually he passes her a note asking her to come to a rendezvous. It all feels like a story by Rivette in which she hardly gives in: she appears with her roommate at the date, and they engage in a role-playing game in which Anna pretends not to speak English and whispers in her friend’s ear, who in turn translates it to the stranger. In fact, it feels like the whole structure of the film is infused with an improvisation à la Jacques Rivette (for example, there is a hilarious scene in which a plastic artist vandalizes his own painting at the exhibition after the curator refuses to lend him money), and the exchange of lines feels like an impromptu mishmash. The feeling of cluelessness on what’s about to happen is exactly what the film bets on – beyond this naive parallel between the two worlds, art and brokerage – and at the same time it foretells Noah Baumbach’s indie cinema, which is based precisely on bits and pieces of life in which sometimes the city emerges more than the characters. There’s a delightful power dynamic between the protagonist, who is intrigued by the broker’s naive and romantic proposals, but prefers to be silent almost at all times, and the man, who is rather accustomed to the encrypted language of brokerage, and now out of a sudden he must translate his feelings to another person, so he voices them out without any filters.

The Pleasure of Being Robbed (dir. Joshua Safdie, 2008)

Joshua Safdie’s debut film (the other half of the Joshua & Benny Safdie duo who gave the world Good Time and Uncut Gems, two gems about the outskirts of New York and the people struggling to the brink of starvation) is definitely a must-see; it’s incredible how much free form and how much freedom there is in this film which follows an unknown young woman, about whom we find nothing at all along the way; still you hop on the journey with her without questioning anything. Eleanore is a girl who pretty much wanders around all the time, finding herself on the thin line between pathological curiosity and kleptomania: she either pick pockets, or sets her eyes on a bag, and each unopened bag is a mystery that she only solves at home (surprise!, sometimes the bags are only filled with kittens and puppies); she might live like a parasite, but at the same time her existence is completely carefree, without any social constraints, like a floating cloud. For example, everything seems to happen on the moment, it’s a type of experience that implies no agenda – here is the first and perhaps the only hint of introspection in the world of the protagonist who, scared of loneliness, has to swallow everything the world has to offer: she steals a purse from a club, she finds a key in it, the key has to open a car, a friend shows up, they look for the car together, they find it and drive together until the morning.

Journalist and film critic, with a master's degree in film critics. Collaborates with Scena9, Acoperișul de Sticlă, FILM and FILM Menu magazines. For Films in Frame, she brings the monthly top of films and writes the monthly editorial Panorama, published on a Thursday. In her spare time, she retires in the woods where she pictures other possible lives and flying foxes.