#Bestof2020 – The Films in Frame editorial staff recommends the best films released and (re)discovered in 2020

2020 hasn’t been the greatest year for any of the industries around the world – we all know that. When it comes to the film industry, where teamwork, festival attendance and meeting with the public are vital, we can say with utmost certainty that it was shaken to the core. Even so, with all the fears that came with the pandemic, Films in Frame continued to deliver content weekly, in (almost) the same formula as until March 2020. We continued on presenting emerging voices, on interviewing those who managed to launch their projects or release their films this year, and we offered you recommendations on what to watch at home and new sections to discover.

Before going on holiday, towards the end of this month, and hoping for a more optimistic start in 2021, when we return, Films in Frame comes with a relatively personal top made by our editorial staff, who recommend the best films released in 2020 and a few titles they (re)discovered this year.

Laura Musat (Editor-in-chief / Thursday interviews)

The best film of 2020

In the last two years I started paying attention a lot more to documentary films and, with this new found interest, I discovered that the local production of documentary films is quite significant. And since the public has also been showing more interest in this area, I’m very glad that I can recommend a documentary film as “the best film of 2020”, which is Acasa, My Home (dir. Radu Ciorniciuc). Call me a sentimentalist, but this film got me hooked from the very first ten minutes, and when I found out that everything started from a social case, from Radu’s (director) and Linea’s (screenwriter) wish to help a Roma family move to the big city and integrate into society, after living for more than 15 years in the wilderness of the Bucharest Delta, I was deeply moved. In this case, it wasn’t just about making a film anymore, but about helping – and thus telling the story of a special family, with good and bad, in such a human and personal way. The film is available on HBO GO, has won numerous awards (Sundance, Sarajevo, Thessaloniki, Transilvania IFF, Krakow and the list goes on), and if you want to know more about it before watching it, I recommend the Films in Frame interview with the team of the film.

Films discovered in 2020

This year I allowed myself to just chill on the couch and watch many of the movies I missed over the years. It’s very difficult to choose only one film, so I will go with a recently rediscovered actress and some of her reference films, which I had the opportunity to watch once more. I’m talking about Catherine Deneuve and the films Belle du Jour (1967), Manon 70 (1968), Peau d’âne (1970) and La Vérité (2019) – the latter was released last year, is directed by Hirokazu Koreeda, and along Catherine Deneuve stars Juliette Binoche (and you can read about the film here).

And bonus, I also come recommending a show, recently discovered thanks to our colleague Stefan Dobroiu, Dix Pour Cent / Call my Agent! – a French production by Netflix, in which a group of artistic agents struggle to get their clients out of trouble. In each episode, there’s a French star appearing and playing as themselves; so far the challenge has been accepted by Cecile De France, Juliette Binoche, Isabelle Adjani, Monica Belluci, or Isabelle Huppert. A very comical series, with well-defined characters, whose personalities evolve with each episode, and also full of unpredictable situations, which keep you on the edge of your seat and inevitably compels you into binge watching. It’s available on Netflix, and Stefan wrote about it here for Films in Frame.

Melissa Antonescu (Editor, Monday News)

The best film of 2020

This year I didn’t get to watch too many movies on the big screen, but by chance I got to the One World Romania festival and thus met Radu Corniciuc’s film, Acasa, My Home. It’s a documentary that portrays a special beauty, and the delicate cinematography contributes to this impression. The director manages to convey a feeling of intimacy, while presenting the subject – a family who lived, at the time of making the documentary, in Vacaresti Delta – without romanticizing or accusing, without forcing the viewer to adopt a certain moral position from which to observe the story. Indeed, there rarely is just one right way to do things, whether we are talking about the place you choose to live in, the way you benefit from or protect nature, or about the significance of education, and in Acasa, My Home every topic is addressed from several angles, thus calling for reflection, dialogue and an open mind.

A film discovered in 2020

If I were to choose only one film from the list of discoveries in 2020, I would go with The Lighthouse, directed by Robert Eggers, a film I had heard about in 2019, but which I kept on my watchlist until recently. Without knowing much about it beforehand, I was fascinated to discover this film choreographed down to the smallest details, from its cinematography with strong expressionist nuances, which creates from the very beginning, along with the soundtrack, a state of never-ending anxiety, to the perpetual shift between reality, hallucinations and Greek mythology. Thomas Howard (Robert Pattinson) and Thomas Wake (Willem Defoe), the main characters and for the most part the only two characters in the film, are captivating, easily changing from pathetic despair to anger and ridiculous behavior, forcing the viewer to constantly be on alert.

I watched the movie with a mixture of horror and pleasure, without being able to take my eyes off the screen.

Ionut Mares (Editor, Emerging Voices)

The best film of 2020

This year film production and distribution, as well as film festivals were seriously affected by the pandemic crisis, so it was quite difficult to keep up with the new releases, whose number has considerably decreased anyway, since the vast majority has been waiting for an alleged return to normalcy. So, compared to the past years, I couldn’t pay that much attention to what international cinema had to offer this year. In this context, which would make it impossible for me to choose the best films, for the sole reason that I’ve seen too few new titles, I would stop at probably the most demanding film of 2020, the absolutely necessary documentary The Exit of the Trains, by Radu Jude and Adrian Cioflanca. An almost three hours long film, composed entirely of archive photographs and documents. The first two hours provide us with official images of hundreds of victims (of over 14,800 killed in the Iasi Pogrom), presented in alphabetical order and edited together with narrated accounts of their deaths given by family members (voice-over narration provided by various actors, filmmakers and personalities from the cultural world), extracted from the post-war trials of the massacres. And towards the end, still photographs of the Pogrom itself follow one another on the screen (disturbing images of corpses on the streets of Iasi or near the “death trains”), without any comment in the background. Through their reparative initiative, Jude and Cioflanca take some of the victims out of the anonymity of the figures recorded by the history books and restore their dignity. When the victims receive a name and a face and a family member evokes their memory, more precisely their final living moments, the drama is no longer something abstract, a linguistic construct and a historical fact (“The Iasi Pogrom”), and becomes more overwhelming through its palpable sense.

Films discovered in 2020

In terms of discoveries, I feel compelled to mention Japanese director Naomi Kawase, since I went through her filmography spanning over 30 years in my preparation for moderating the masterclass she held online at the Les Films de Cannes à Bucarest festival. Of course, I knew her fiction films from the last ten years or so, because almost all of them were selected at the Cannes Film Festival. But the real revelation came from watching her best films made in the ’90s and 2000s – both her extremely personal and intimate documentaries (about her adoptive mother or the search for her father) and her first fiction feature films. Her debut, Suzaku, which brought her Camera d’Or at Cannes in 1997, thus becoming the youngest recipient of this award (she wasn’t even 28), and Shara, released in 2003, both with stories set in the Nara region, the filmmaker’s birthplace, are two films of admirable formal and narrative freedom. Films that talk about the complexity of family relationships and where the permanent shadow of death is counterbalanced by the sincere joy of sharing a life together.

Georgiana Musat (Editor, Monthly Top)

The best film of 2020

I went over and over again through the films I’ve watched this year at festivals and on various platforms and, no matter how I go about it, I always seem to turn to Just Don’t Think I’ll Scream (dir. Frank Beauvais), seen at the One World Romania festival. Despite the fact that the film was released in 2019, it could easily summarize this year. An anguishing quatrain portraying your typical cinephile living in isolation (following the terrorist attacks that completely paralyzed France, as well as a painful break-up, when Beauvais self-exiled at home), who feeds on cinema, yearning and fried eggs. Initially suffering from a writer’s block, Beauvais ended up making a film about his own crisis: he binge watched 500 films or so and turned them into an essay film through which he exorcized his own experiences, although he is perfectly aware that, by seeing them for what they really are, the dramas of the past are beginning to become more and more harmless.

I won’t generalize, but all the misery I’ve been through during the pandemic has translated, as in this film, into a movie addiction, which made me turn to some frowned upon methods (pirating, God forbid!) in order to get my hands on Jacques Tourneur, Jean Cocteau, Wang Bing, etc. and I had time to hate and love my job a billion times, as if in an existential loop from which it seemed impossible to get out.

A film discovered in 2020

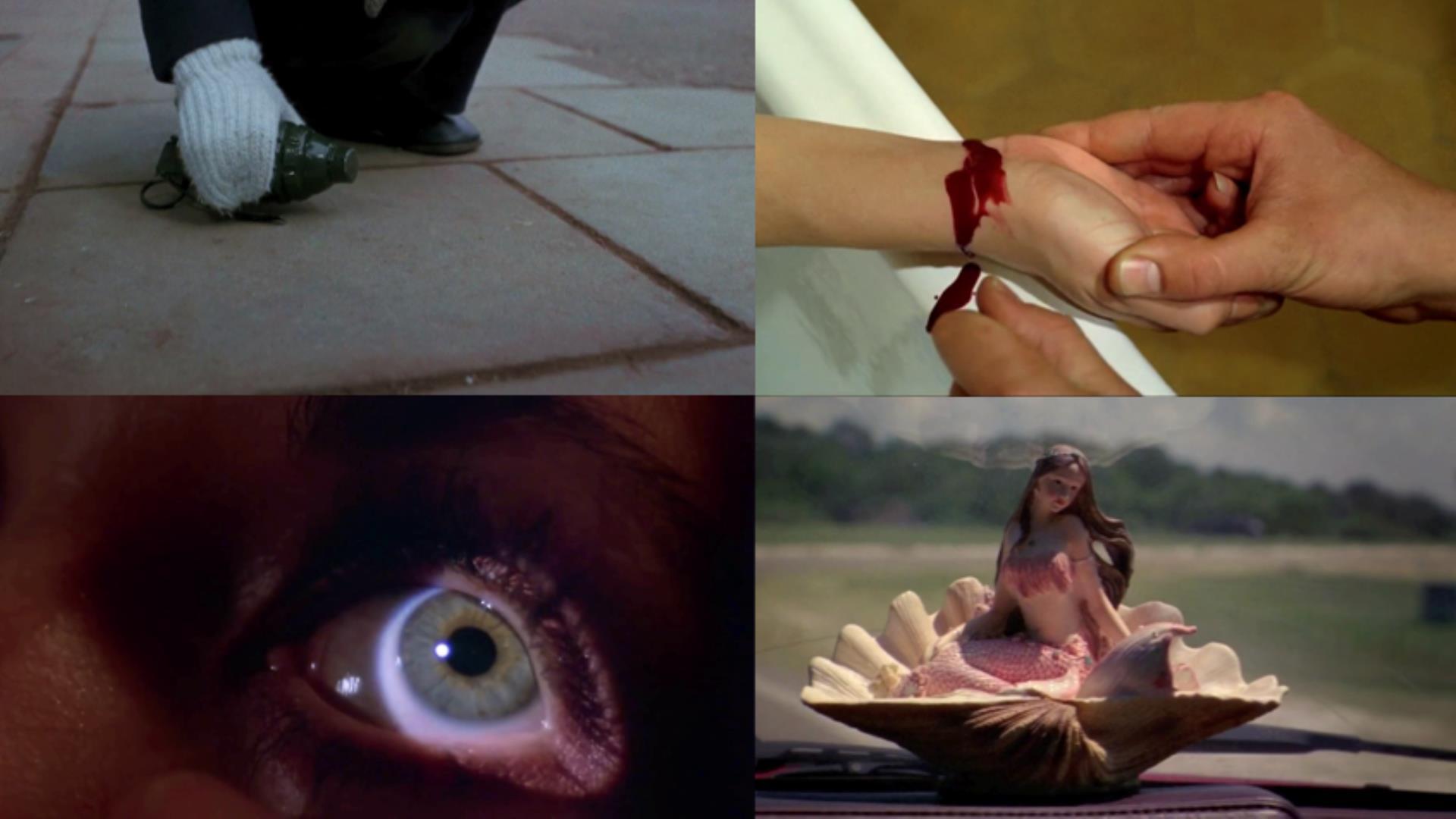

By far the most memorable experience this year is a film with Isabelle Huppert, which I’ve been postponing for several years and finally reached via Mubi. Malina (dir. Werner Schroeter, 1991) follows a Zulawskian writer who appears to be in a self-inflicted purgatory; half the time she is surrounded by flames, sweating from all her pores, begging one of her lovers to get her out. Schroeter’s film is an adaptation of Ingeborg Bachmann and is an incredible portrait, in which Huppert performs the hysteria of a character who is impossible to tell if she’s alive or dead, if she hallucinates or has come to live in a self-made universe, where the torment of creation is overcome only by the torment of oscillating between three men, all abusive characters in her life (her father, her husband, Malina, and her lover, Ivan). To summarize a small part of the surrealist scenes in the film, the protagonist shifts from one state to another, moves from one place to another – she wakes up unable to leave a restaurant, bleeds in front of a construction site, ends up in the bathtub, where she keeps her feet up while washing, then, a little later, disguised as a Victorian princess, asks Prince Ivan to save her from her father’s tyranny.

Flavia Dima (Editor, Thursday interviews)

The best film of 2020

I caught myself going back again and again to this year’s edition of Berlinale, after the lockdown and everything that followed (I was among those who avoided going to any festival for the rest of the year). Obviously, it was inevitable. It quickly became clear that this year’s Berlinale was the last major festival to physically take place before the European pandemic broke out – already in its last days, news about Lombardy and deadly cruise ships were reaching us -, which softened the atmosphere from the scene and gave it a nostalgic aura: because, ultimately, the general opinion was that the first edition under the artistic direction of Italian Carlo Chatrian wasn’t living up to expectations (and there were quite a few). The promise to relieve the grand festival of its deadweight was not delivered, the interesting Encounters section only misled and created an artificial race with the Official Competition, and with the Forum at the same time (so what’s left for the Panorama?), the big names delivered in a predictable way, but in no case with career highs, and there were no surprises whatsoever. But, to put it into perspective, with the vast majority of the most expected films of the year being put on hold, the catastrophic cancellation of the Cannes Film Festival and a successful Venice edition, but somewhat obscure – considering, even this disappointing edition of Berlinale was endowed (as this duo of memory and affection often does) with a late romance that further sweetened what felt at the scene as a flop.

Finally, perhaps this long and slightly useless parenthesis is in fact an attempt to justify the fact that, after so many months during which the consumption of cinema, on a large scale, has been privatized (and I use this term in its political, as well as economical sense) due to the pandemic, and although I saw countless great new films this year, many of which I had the honor to include in the BIEFF.10 selection, the one film that haunted me the most was Days / Rizi, by the Taiwanese master Tsai Ming Liang.

Days is the kind of film that can easily shake off its entire load in a private viewing space, where the “Space” key is at arm-length distance, where the pinging message can be replied to in a mere moment, where a quick bathroom break doesn’t entail raising ten people of their seats or stumbling through the dark, and so on. How can you watch that beautiful and long scene of sexual intimacy between Kang and Non without being flooded with that thrill of quivering shame you feel when you see such images in the company of others, that playful embarrassment that enters into a direct dialogue with the screen? It’s a venal sensation that cinephiles and critics in particular suppress, as they suppress most of the emotional reactions that cinema brings into our being in direct contact – but which still remains deeply woven into the fiber of movie theater and cinema mythology, ad extenso. In the absence of these sensations, which the long scenes of everyday life that precede it also play a part in, Rizi‘s nocturnal finale is a simple narrative ending – the two go their separate ways. If watched in a movie theater, the ending leaves you with that bittersweet feeling one can experience in any amicable and inevitable parting, and with the thought that you now must bid farewell to the fiction world of the film – ineffable sensations that make me say that this is the film of the year, for me. (I wrote more about it in Echinox Magazine.)

Films (re)discovered in 2020

Since it was a year dedicated (at least in part) to recouping – and at least what’s cool about it is that it seems to have been a global thing -, I have great reluctance and shame to name the titles that follow (some I revisited, some were picked up from scratch), but I’ll try to commit to it: starting with For a Few Dollars More (1965), the central piece in Sergio Leone’s masterful spaghetti western trilogy, seen together with Peter Tscherkassky’s masterful experimental short film, Instructions for a Light and Sound Machine (2005) – two films that use the same images, one by creating them, the other by reusing them, both deeply infused by the idea of death and inalienable cinematic mythology. Two other extraordinary titles from the found footage area would be Just Don’t Think I’ll Scream (dir. Frank Beauvais, 2019) and Heimat ist ein Raum aus Zeit (dir. Thomas Heise, 2019); two extraordinary classics – I Was Born, But … (dir. Yasujiro Ozu, 1932) and An Affair to Remember (dir. Leo McCarey, 1957); two films from the nineties – A Moment of Innocence (dir. Mohsen Makhmalbaf, 1996) and Irma Vep (dir. Olivier Assayas, 1996).

I will conclude with Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (di. Apichatpong Weerasethakul, 2010), which I saw in March in the very beginning of the lockdown (which kicked off with quite the anxiety), in a half-asleep state that made me understand why the filmmaker not only doesn’t get upset with viewers falling asleep during his films, but actually encourages them to do so – I partially woke up after dozing off during the last sequence and made out only half of the final image of the ritual and part of the words whispered during it, but then I completely fell back to sleep (until the next day) before the credits even entered the screen; and after this experience, I feel I finally fully understood his words and possibly his cinema.

Victor Morozov (Editor, Friday reviews)

The best film of 2020

I discovered in Rotterdam, in January – it was the world of yesterday, before the global pandemic became an inevitable nightmare, a 200-minute feature film, El año del descubrimiento / The Year of Discovery, coming from a Spanish director named Luis López Carrasco. This film hit me hard (got a punch in the face, as one would say), after walking around the city center with no sense of direction and gradually grasping on the density of its story and the complexity of its shape, but also realizing the fact that a single viewing will not be enough to reveal all its layers (political, social, aesthetic). When the film – which left the festival empty-handed – finally triumphed two months later at the Cinéma du Réel, I was happy to think of all the cinephiles who will be lucky enough to meet Carrasco’s film, after receiving such encouragement.

I meant to stop here. Then I realized that, by doing so, I would have ignored an essential level of my cinephilia. I anxiously waited for one particular film in 2020 (the rest of them, given this dry year, I saw as happy events): Le Sel des larmes by Philippe Garrel. And what does it matter that it’s perhaps the weakest film he made in recent years? For me, a film by Garrel will always have an aura of its own.

Films discovered in 2020

Caro diario / Dear Diary (1993) by Nanni Moretti, because it seems that cinema has never invented a more graceful way to embrace the world and shout, one by one, the joy, the anger, the pain of being part of it.

Recordaçoes da casa amarela / Recollections of the Yellow House (1989) by João César Monteiro, because it showed me how cinema can find, in the very heart of abjection, a hedonistic grace capable of sublimating absolutely everything.

U samogo sinego morya / By the Bluest of Seas (1936) by Boris Barnet, because he blinded me with his faith in an incandescent feeling and in cinema’s ability to record the moment of grace in which a gesture ends up defying any predetermined limitation. And because it reminded me of what it means to watch a movie at the cinema, alone or with friends, and how important it is, in these times, to fight so that this experience is not lost. I’ve already seen people in the industry (professionals of the profession, as Godard used to say) who didn’t mind sharing with us how nice it is to watch a movie in the comfort of your own home, on the laptop screen. With those people – and here I feel like citing Serge Daney, I will never be able to be friends.

P.S. And since we’re on the subject – personally, it’s been a bad year in terms of cinema discoveries. But it was the year in which I (re)discovered the texts of Serge Daney, the one that made me understand that between us, the ones who deal in selling films by only making use of the written word, more important than the films themselves is the way we talk about them.

Calin Boto (Editor, Footnotes)

The best film of 2020

Even gay porn has its saints. Canonized – Kenneth Anger, Peter de Rome, Joe Gage, Jack Deveau, Wakefield Poole – and contemporaries – William E. Jones, Bruce LaBruce. Well, Evan Purchell is a pious fellow. It all started with an Instagram account on which the researcher started to post (and still does) promotional material of the ’70s and’ 80s American (sometimes French) gay pornography. An extinct world, one of gay subcultures, most of it unconsumed at the right time in the eastern space for obvious reasons. But that doesn’t make Ask Any Buddy, the second part of the project (the third being a podcast), approachable only by a non-Western audience. On the contrary, since pornography in general, and gay pornography in particular, hasn’t just suffered from disrupted development around the world (a rare disease among film genres), but also from stigma on all sides. Social stigma, obviously, then aesthetic, and finally, ideological. There’s only a few of us who do not have an opinion on porn – that it’s a jumble, not cinema, of toys, dressed up clowns, flashy lights and noisy decoys. That it’s bourgeois and useless for social purposes, apolitical or reactionary, completely toxic by what it presents and claims to be. That it’s, of course, dirty. That’s why Ask Any Buddy, a video mashup, leaves no room for redundancy or yawning; the eyes watching it won’t have time to relax not even for a minute. Purchell’s selection mainly works around certain tropes – surrealism/mysticism, sex in abandoned buildings, in public bathrooms, in the subway, in the club, dancing, tender relations, small enticing shows, activism, etc. From this very brief list, it’s quite clear that the film is a demystifying introduction into gay porn, at hand for anyone who wants to confirm or refute their preconceptions and half-measures. A jumble? On the contrary, the golden age of gay porn, which Purchell also turns to for his mashup film, was very ambitious on a formal level. That’s why Kenneth Anger is a saint, because his legacy has supported much of this formal ambition. Peter de Rome’s films, for example, could easily find room in the experimental cinema convention, and if anyone were to ask me, Wakefield Poole surpassed Derek Jarman in the 1970s in many ways. Apolitical, reactionary, useless? There’s no rule. Dirty? Sure! But I don’t do justice to the film by presenting it as a lesson. Far from being pedantic, the director is playful, funny and shameless, and Ask Any Buddy is like a hall of mirrors, a study of infinity, because porn doesn’t mean only sex, but also hard stares and soft gazes, and this is exactly what Purchell includes in his collection – he looks, together with the viewer, at what the camera looked at on that point, that is, boys watching boys having sex knowing they are being watched.

A film discovered in 2020

Children should be given art albums to draw on without any constraint. I had this strange revelation one afternoon when I got my hands on an art album with reproductions that accompany an essay written by Eugen Schileru, published post-mortem in the form of notes. And oh no, a little brat had scribbled all over Morisot’s engravings and Manet’s Olympia! Anyway the revelation didn’t come to me immediately, but hours later, when I came out completely frozen from the screening of Gábor Bódy’s colossus, Nárcisz és Psyché / Narcissus and Psyche (1980), which the people from Hungarian Film Week had the visionary courage to hold outdoors in mid-November. What the little brat, who sabotaged my foray into impressionism, and Bódy have in common is not so much about intention as it’s about result – to have some well-defined shapes, clear and rigid lines, and then totally trash them, leave them with a rabid coolness, but still keeping the relics of the original. Narcissus and Psyche is a period piece, a melodrama that takes its essence from Psyché, the experimental novel by Sándor Weöres, and from the myth of Narcissus. This Narcissus, here under the name of Laci Tóth, is in fact an intellectual, a writer and a physician, who himself works on a book based on myth, and Psyché / Erzsébet Lónyay (Patricia Adriani) is a young rebel among the aristocracy, who indulges in defiant decadence and the on and off love for the intellectual, played by Udo Kier, painfully handsome, glacial eyes and oxygenated blond hair. Their story is a cafe legend, or so Bódy presents it, within the frame of a story told in several voices by seniors, people of a bygone regime, those who resurrect folklore. The narrative, this ambition that wears out and ennobles cinema, didn’t stop the director from working on his each and every sequence like a jeweler, small jewels that break into pieces before our eyes. It’s a film that reaches greatness without taking the shortcut given by weight. Loyal to the myth, the director follows Narcissus’ self-cannibalization process, physically and spiritually, over a century and a half in which the fiery creatures, the mystical protagonists of Bódy, might accept decay, but won’t risk a single wrinkle. As I said somewhere else, if Bódy had been exported in the right way, to the right place and time, then he would have definitely been included along Rivette, Lynch or Jarman in every introductory study.

Stefan Dobroiu (Editor, Trailers of the month)

The best film of 2020

A serious candidate for the 2021 Academy Awards, The Trial of the Chicago Seven (written and directed by Aaron Sorkin) has a lot of flaws, but they fade to nothing in comparison to the efficiency with which it describes what can happen when the authorities (police, officials, politicians) forget in whose service they carry out their activity. For Romanian people, the parallels between the protest against the Vietnam War that took place in 1968 in Chicago and the frightening August 10, 2018 in Bucharest are pretty much obvious. The Trial of the Chicago Seven reminds us that no sacrifice is too great in order to blow up the bubble inflated to extremes with the thin air of power and remind political leaders that they need to obey the will of those who elected them. The movie is available on Netflix.

A film rediscovered in 2020

I saw In the Mood for Love (dir. Wong Kar-wai, 2000) in 2001, when it was presented on the big screens in Bucharest at the Asian Film Festival. It’s a film worthy of being rediscovered, not only because it has withstood the two decades since the world premiere (Tony Leung Chiu-wai won the Best Actor Award at Cannes in 2000), but also because there are few feature films that can portray the vulnerability and fragility of human emotions in such a genuine way, and especially the endurance of the human being. Wong Kar-wai performs a successful cinematic magic number with In the Mood for Love, and there is no better time to indulge in this magic than the end of a year that has shown us once and for all how fragile and vulnerable we really are.

An article written by the magazine's team