“We are ridiculous and don’t know it.” When film critics look at the Olympics

Cinema and modern sports: two inventions born almost simultaneously, using a vocabulary so similar – movement, spectacle, corpor(e)ality – that they can almost denote one and the same thing.

Judging by the frequency of forays into the realm of sports imagery, it seems that almost all film critics are failed sports journalists. Of course, this is a predominantly French affair, for, beyond certain clear personal affinities, it is there that this skewed perspective, which loves to play away, in the field of “parallel, ancillary activities”, as Éric Rohmer put it, has been most consistently explored. Sports have long served as a convenient metaphor: with its primary interest in framing (nothing more similar between a screen and a sports field), with its eminently mediated nature (images that interpose equally between actors and athletes, on the one hand, and the public, on the other), it was always available.

At some point, in the immediate aftermath of the democratisation of television (the ’50s), sports and film began to overlap, each in its own way becoming a laboratory for playing with images. So, with the upcoming Paris Olympics, it’s time to revisit these parallel histories, now that both sports and film seem to have reached a new classicism: far from fancy experiments with images, the stadium and the movie theatre today generally act as an immutable landmark, a shelter from the audiovisual blizzard – and as a nostalgic locus for old-fashioned cinephiles. That is precisely why we must be on the lookout for any changes.

Image + Movement

A short preamble. Before being entertainment, sports and cinema fulfilled a role of sanitising the social fabric. Sports is, first and foremost, “physical education”, and cinema, “moving images”. The former leads to a better knowledge of oneself, an understanding of the body’s capabilities that have long been dormant, while the latter contributes to knowledge of the world, from the microscopic infinity to the infinity of distances. Both also serve a nationalist function: the need for sports on a mass scale arose after the French army’s great defeat by Prussia in 1870, which was also dominant in terms of physical fitness; and cinema quickly developed a utility for a better relationship with the colonies, with images used as information, real windows of knowledge – and repression – of the other. Sports means rebirth, and cinema, progress at any cost.

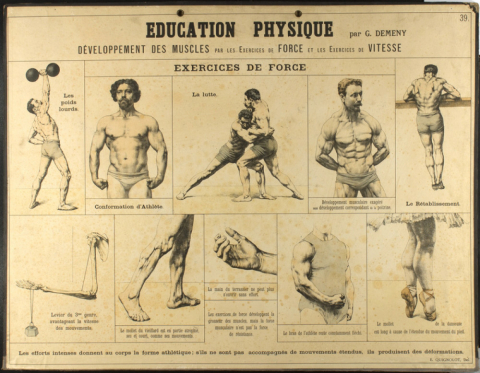

The list of parallels can go on indefinitely. The fact is that, as theorist Patrice Blouin puts it, “the image is not at the end of sports, but right at its beginning.“ The renowned scientist Étienne-Jules Marey is an integral part of this symbiosis. Ideologically, first and foremost, as a promoter of the fight against human degeneration, to which sports is a timely remedy for the whole nation. But also much more concretely: after all, the pioneer in movement study, the inventor of the chronophotographic gun in 1882, could only find this momentum in the new body mechanics exciting. Various sports practices are becoming widespread and with them, a new attention to the body’s appearance, as well as to exercising. Various guidebooks appear, detailing in an exalted-eugenic way this relationship with the body, which Marey’s visuals will refine and regulate with scientific precision. The era is marked by an unprecedented valorisation of the act of cultivating one’s physique.

In fact, because it deals with movement (and its modulation), sports becomes one of Marey’s favourite fields, along with the military domain and nature observation. His encounter with Georges Demenÿ, a former gymnast, pioneer of physiology, and future author of textbooks such as Éducation physique des adolescents (1897, i.e. Physical Education for Adolescents) or Guide du maître chargé de l’enseignement des exercices physiques dans les écoles publiques et privées (1900, i.e. Teacher’s Guide to Physical Exercise in Public and Private Schools), is certainly decisive. It would not be an exaggeration to see in it the very invention of cinema. Together, they will produce hundreds of sequences presenting sports movements, proto-films that will help to create an essentialized, simplified language for disseminating sports to the general public, just as they will deepen the knowledge of the body’s capabilities. With a dual objective – scientific and artistic – these visual samples constitute, as Antoine de Baecque writes in a recent history of sports in the Belle Époque, “a form of universal grammar of the gymnastic body”, the first testimonies of “technique, history, and cinematic technique”. A brief selection of these is available on the French Cinematheque’s platform Henri, where we see various athletes – some of them completely naked – throwing the discus or competing in the long jump against an abstract background or, more rarely, revealing the aristocratic and male world in which sports were born.

Why Not Television?

The professionalisation of sports – starting with the establishment of the International Olympic Committee and the first Games (in 1896 in Athens) under the guidance of Baron Pierre de Coubertin, an aristocrat educated on the sports model of British schools and academies and passionate about Ancient Greek culture – is too long a chapter to be detailed here. What interests us, however, is a kind of by-product of this tumultuous history, namely the birth of the sporting spectacle. As Élisabeth Lê-germain and Philippe Tétart conclude, “the sporting spectacle, with its ways of heroization, with its legends and tales already rooted in collective memory, manifests its omnipotence intertwined with the stakes of representing the event [at the 1924 Olympic Games].” A hundred years later, back in the same place, the act of looking from film culture to sports seems both well-established – “many people have been here” – and still somewhat unusual. But a few key milestones have already been set.

Perhaps the most important milestone comes, quite improbably, from the luminary of a classicist vision of cinema, assimilated with the force of the noblest of arts: future filmmaker Éric Rohmer. In 1960, the French film magazine Cahiers du cinéma experienced a turning point. Rohmer, who was the editor-in-chief, was trying to defend his more and more contested approach and vision against the “modernists”, a rival faction of critics led by the iconic figure of Jacques Rivette and interested in younger and more experimental voices. Coming, therefore, from a fervent admirer of classic Hollywood cinema, this article by Rohmer is at least paradoxical – by no means an orthodox stance: in fact, it aspires to align itself in extremis with the filmmaker’s great interests precisely through a bold account of a screening (in a movie theatre) of a 40-hour serial television reportage on the Rome Olympics. Strange only in appearance, this digression finds its ultimate basis in a form of exaltation of the perfect physique, a fascist idea that Rohmer was later criticised for. In any case, for him, there is hardly a difference between the sublimated pursuits of the American studio grandmasters and this televised reportage on athletics, meant to inform about the immediate present and then be forgotten. Shock and awe: it is hard to imagine the effect at the time of this provocative approach, with Papa Rohmer writing, “I will not say that this spectacle was beautiful as a film, but beautiful as a film I love, beautiful as Howard Hawks’ films, if this example can help me make my point.”

It is not at all vain, but in fact necessary, to consider carefully everything that can be projected on a cinema screen, even when, as in the present case – an extreme case – it is not even cinema.

Éric Rohmer wrote in The Photogenics of Sports: The Olympics in Rome

In his article The Photogenics of Sports: The Olympics in Rome, Rohmer establishes this practice of transferring the tools and vocabulary of film analysis to slightly different objects, glossing with delight over the suspense caused by the mise-en-scène, as well as the idea of emotion. One of his great inventions is to praise the directing team for recording the full length of the events, offering more than a pre-edited highlights sequence. You can take Bazin out of criticism – the mentor had already died in 1958 – but you cannot take criticism out of Bazin, with his privileged inscription of the real in the image: this is how Rohmer finds himself approvingly evoking the presence of “empty moments”, dead time which, instead of diluting the euphoria, amplifies it because it’s delayed by “a thousand ancillary and yet essential circumstances”, such as preparations, false starts, the athletes’ tension, etc.

Brilliant in intuition and not at all reactionary, Rohmer can argue that “the fact that races and competitions take place simultaneously – which might be upsetting for the spectator in the stadium – only reinforces the interest and coherence of the whole.” Thus appears the idea that television broadcasting enhances and complements the sports experience. Reversing the always disdainful comparison between cinema and television, Rohmer concludes prophetically: “Therefore […] it is not at all vain, but in fact necessary, to consider carefully everything that can be projected on a cinema screen, even when, as in the present case – an extreme case – it is not even cinema.”

The Serge Daney Moment

In the 1980s, after a period of Marxist-Leninist dogmatic fervour that prohibited any interest in debased and frivolous objects, sports broadcasting re-entered the realm of French film criticism. The World Cup is analysed in round-table discussions in Cahiers du cinéma, where critic Charles Tesson publishes his article on the mise-en-scène of football, Le ballon dans la lucarne (i.e. The Ball in the Skylight). Serge Daney’s long-standing interest in tennis cements the marriage between the stadium and the movie theatre. Daney, a frequent traveller, goes to Los Angeles for the 1984 Olympics, hosted by the Americans, who also have a monopoly, through ABC, on televising the event. The film critic sends a series of articles from L.A., transitioning from the aesthetics of the TV network to the live experience of watching a match with the fans in a crowded Sunset Boulevard joint.

A common thread runs through all these critical interventions: the need to take a stand on the cinema-TV divide. Of course, the most interesting examples, like here, choose to counter the usual hierarchies, speaking freely about a medium often looked down upon, like television. But even this moment of unlikely spotlight on television cannot help but betray the inherent exoticism of the practice: coming from a film critic’s perspective, TV will never be more than an alterity. But this is not just a limitation, a weakness – it is the very point of interest of these “displaced” texts because their inability to internalise television, their obstinate view from the outside, makes them the only ones capable of accommodating the distinct, specific topography of the images or putting this audiovisual media squabble into perspective. The exercise is profitable only if the tension between the images is preserved. Otherwise, it’s “every medium for itself”.

Daney begins his first (and most important) article, Nouvelle grammaire (i.e. New Grammar) with this very idea: “The annoying thing about television is that we still talk about it using the words of cinema. We’re ridiculous and don’t know it. We talk of shots, we talk of montage, of camera movements, of flash-backs. We act as if time in television was linear and its space was homogeneous. We (and our poor words) are completely wrong. We should change the vocabulary one of these days.” In the good Cahiers tradition, Daney also launches a challenge: he is not sure, however, that this cinematic language can be overcome. He is not sure that all the contradictions of television, as well as those of the media among themselves, can be highlighted without terms like the aforementioned ones.

At least, not in 1984. Daney, moreover, dedicates his fantastic text to oscillating between the two, comparing the idea of a close-up in cinema with the idea of a replay in television: two solid trademarks that have come to summarise the power of the respective media. The slow-motion replay remains the trump card for the directing teams who are not so keen on inventing their grammar every second, but rather rely on the viewer’s capabilities of immediate recognition. Daney wryly observes how this “suspension of the flight of time”, this act of “verifying, admiring, reliving, or judging” generalises towards “all arts”, which “have henceforth entered the era of hypertrophied sampling”. Coming from sports and applied, for example, to dance, the replay is like pre-digested food for the viewer, isolating from the outset, on behalf of everyone, what needs to be seen, what is important.

The annoying thing about television is that we still talk about it using the words of cinema. We’re ridiculous and don’t know it. We talk of shots, we talk of montage, of camera movements, of flash-backs. We act as if time in television was linear and its space was homogeneous. We (and our poor words) are completely wrong. We should change the vocabulary one of these days.

Serge Daney wrote in Nouvelle grammaire

As for the TV close-up – “the new black holes of the TV galaxy: a coach’s face, a celebrity or star in the stands, American flags waved by the cheering crowd” – Daney’s formidable insight allows us to see how much television broadcasting has stagnated from then until now, incapable of inventing new figures of speech (with few relevant exceptions), reverting to the same old tricks when it comes to injecting some ready-made excitement into the bored hearts of viewers (see this inflated-weak spectacle that was EURO 2024). Attuned to television’s practices, Daney strives to point out its specific approaches, those that seem to belong to it alone – except they do not.

Marey’s Postscript

In 2008, Patrice Blouin wrote an extraordinary double essay, Faire le tour. Voir les jeux (i.e. Making the Tour. Watching the Games), dedicated to the Beijing Olympics and the Tour de France. Conceived as a journal and explicitly intended by the author as a response to Rohmer’s seminal article, the half concerning the Olympics speculates in a spirited and diverse way, according to the day’s events, jumping from the opening ceremony to the Speedo swimsuit that provided extra buoyancy to swimmers (since banned) or to the fencing broadcast. Of all the thinkers analysed here, Blouin is the fiercest opponent of what he calls the “cinematic paradigm”, that is, the idea that cinema is the discriminator, the “good image”, the accurate timekeeper in audiovisual matters. In fact, in 2017, he releases Les Champs de l’audiovisuel (i.e. The Fields of Audiovisual), which rewrites the history of audiovisual in more egalitarian and inclusive terms, giving equal parts to television, reel, and so on.

Therefore, for Blouin, there is no inferiority complex. Building his argument in opposition to all conservative lamentations (even about the VAR in football) that claim this intrusion into the realm of images distorts sports and distances it from its urgent, unmediated essence, Blouin argues that, on the contrary, all these additions serve this nature – in other words, that from the very beginning, sports and image have fought the same battle. Not only is cycling, for instance, a purely media affair – the Tour de France having been launched in a promotional campaign for a newspaper by a shrewd and cunning entrepreneur; but sports have risen since ancient times on the concept of image, working in line with the narrative expectations of spectators (heroes, superhuman achievements, etc.) and later in line with the format imposed by television. For Rohmer, TV complemented sports and allowed us to watch it in its entirety, not selectively. For Daney, TV influences sports, imbuing the game with a certain “telegenic” quality. In Blouin’s case, it has become impossible to determine how much of the spectacle we witness is due to the ancestral sport and how much to new media.

The loop is therefore complete. For if it all began with Marey and his in-depth examination of the athlete’s movement, the spectre of the same inventor hovers over the new technical inventions in broadcasting. Among the films selected by the French Cinematheque, it is enough to watch the one entitled Course à grands pas (i.e. Great-stride running), where the athlete’s gallop perpendicular to the camera lens is rendered in ever slower motion, transitioning from the almost dizzying fluidity at the beginning to a robotic, jerky step. The photo finish is just around the corner, already contained in this splendid insight into movement. With its hyper-fast chronophotographic gun, the new photo finish technology that lines up athletes in a flattened frieze, a one-dimensional space-time, is an update to Marey. As is the VAR, the most contested recent invention in sports broadcasting, which fragments the play and reduces it to the strange status of immobility.

Film critic and journalist; writes regularly for Dilema Veche and Scena9. Doing a MA film theory programme in Paris.