No two football games are alike

An exponent of popular culture, football has a symbolic power to mobilize the masses. Accessible to everyone, from economically developed countries to the most disadvantaged corners of the earth, this sport, known as the most democratic of them all, fulfills the idea of community, of belonging to a group with shared values. Rather than going for films that focus strictly on the athletes’ evolution from amateurs to pros, I have chosen to revisit a few titles that treat football as an exponent of entertainment and cultural phenomenon. Different in style, ranging from films bordering on home video (The Second Game) to fiction works that inspire a change in social morals and values (Offside), the selected titles show us a different side of the number one sport, this contemporary religion that we all worship in stadiums or in front of the screens.

Offside (dir. Jafar Panahi, 2006)

Offside follows a group of young women disguised as men who try to sneak into a football stadium during an important match. As the title of the film suggests, in Iran, the playing area is off-limits to women, only men are allowed access to live football games. Starting from a simple premise, Panahi goes further into exploring more complex aspects of Islamic society such as traditionalism and religious fanaticism. The girls are caught by soldiers who have little reason to prevent them from watching the game other than following orders and some slight reliance on the ban as a means of protecting dignity. Coming from similar places and only doing their national service, the young men tend to be on the side of the protagonists who are genuinely interested in football. Essentially a film about sports, Offside places the game outside the frame. Like the female fans caught by soldiers and put in a holding pen on the stadium roof, we hear the roar of the crowd without seeing a single thing, only trying to assume what is happening on the field. Subversively, Panahi’s approach questions inequality through the very implementation of prohibition: the holding area becomes a symbol of the common passion for football. The protagonists’ tactical and technical knowledge contradicts the preconceived ideas according to which football is essentially a male sport, and the soldiers’ occasional commentary on the match gives them a chance to witness the event. The conditions on the set mirror the script, with the director illegally filming at an actual stadium during a qualifying match for the Iranian National team and circumventing the ban he was under at the time.

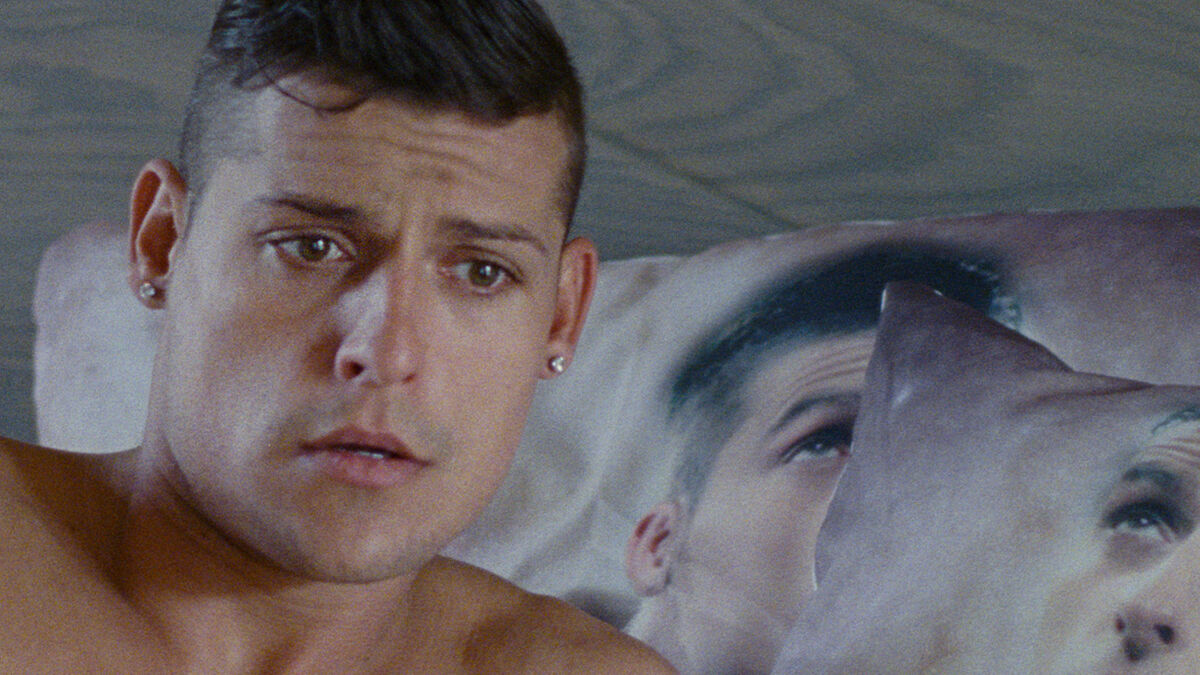

Diamantino (dir. Gabriel Abrantes, Daniel Schmidt, 2018)

A multifaceted artist, best known for his short films, Gabriel Abrantes co-directs this parody about a fictional world-class football player who suddenly loses his mojo. Loosely inspired by Cristiano Ronaldo – the protagonist is also Portuguese, has a similar look and persona as the Manchester United star – Diamantino renders a harsh criticism on sports marketing and consumer society. Presented as a first-person narrative resembling a children’s story, the film outlines the stereotypes of elite football, with (badly) family-managed athletes and potential tax evaders, focusing on an innocent and docile individual who puts his talent on the line for the good of the family. The surreal opening scene highlights football’s power of fascination, with its stadiums, these modern cathedrals, crammed with fans adulating the players like some Renaissance gods. A piece of solemn music accompanies the protagonist touched by divine grace as he scores a goal, during which he has the revelation of genuine ecstasy: the joy of running like a child on the field with some giant puppies wrapped in a fluffy cloud. What follows is a mishmash of genres, from bioethical science fiction to mediocre queer crime drama. The gullible and big-hearted player, much like a socially inept Forrest Gump, is at the center of a conspiracy seeking to replicate his talent for immoral purposes. The greed of those who feed on Diamantino’s fame knows no limits, manipulating him as a replaceable pawn with no personality. Abrantes and Schmidt portray a fantasy world in which football is instrumental, humorously taking on a kitschy aesthetic: interiors decorated with trinkets portraying the star and ads that celebrate virility but conceal any sign of the football player’s humanity.

Diego Maradona (dir. Asif Kapadia, 2019)

Asif Kapadia’s documentary presents never before seen archival footage of the famous football player and focuses, with few exceptions, on the time he spent in Naples. With a conventional structure divided into the discovery, the peak and the decay of the Maradona myth, the great achievement of the director, an expert in biographies, is to bring the material together in an engaging manner, similar to cinema verité. Featuring the voice-over of Maradona himself, Claudia Villafañe and various Argentinian journalists, the film illustrates Neapolitan fans’ obsession with Diego, whom they have turned into God. From the graffiti on the walls of the Italian city to the iconic goal known as “the Hand of God” in the quarterfinals of the 1986 World Cup, Kapadia outlines the portrait of a demigod, worshipped not only by football fans but as a symbol of marginalized Italian people, despised by the developed industrial North. A memorable scene shows the young player arriving in Naples, determined to make a name of himself, and follows him up to the warm welcome he gets on the field. True to his humble origins, coming from a shanty town on the outskirts of Buenos Aires and playing for the working-class club Boca Juniors, Maradona fits in with the world of Naples right away, encountering here many of the problems he lived as a child. Poor and dirty, run from the shadows by mafia clans, Naples was considered a disgrace to Italy, and the Argentinian player’s belief in his chance to elevate this team raised him to heights never before seen in football history. A masterclass in editing and script structure, the film encapsulates in the micro-universe of Naples the inner conflict between Maradona the myth and Diego, the modest boy who plays football to support his family. Diego Maradona is the ultimate portrait of football myth, raising its idols and knocking them off the pedestal from championship to championship.

The Second Game (dir. Corneliu Porumboiu, 2014)

The Second Game is the VHS recording of a Steaua – Dinamo football derby played in the winter of ’88 and broadcast by the National Television, featuring commentary by the director and his father, the referee of that match. An event representative of the austerity of the times, filmed in the period before the Revolution, when the noose of oppression had reached its maximum grip, The Second Game is a sports archive document but also holds personal meaning. As the director confesses in the opening scene, when he was seven years old, he was threatened on the phone by an unknown person that if he didn’t convince his father to quit his job as a referee, he could return home in a coffin. Starting from this premise, Porumboiu-the son urges his father to recount the importance of the match, a face-off between the team supported by the Securitate and the team supported by the Army, Ceaușescu’s favorite. The two very different approaches to the game reflect the commentators’ individual relation to the events: while the son seeks the poetics of imagery and questions the playing conditions during a heavy snowfall, the father is rather indifferent to the weather-related restrictions, the presence of potential informants or the political consequences on his job and personal safety. Adherent to a non-intrusive style of refereeing, Porumboiu-the father rarely applies penalties, letting the game flow without unnecessary disruption. Despite the director’s tendency to find similarities between the football match and cinematography, trying to turn his father into a film character, the former referee’s pragmatism sabotages any hope of stylization: football is ephemeral, an experience lived in the present, and nobody cares how it used to be back then.

Film critic and programmer, she collaborates with various international film festivals. Her writing has appeared in publications such as Senses of Cinema, Kinoscope, Indiewire, Film Comment, Vague Visages and Desistfilm. In Spanish she has written for Caimán Cuadernos de Cine and in Romanian she collaborates with FILM magazine. Programmer and coordinator of Tenerife Shorts.