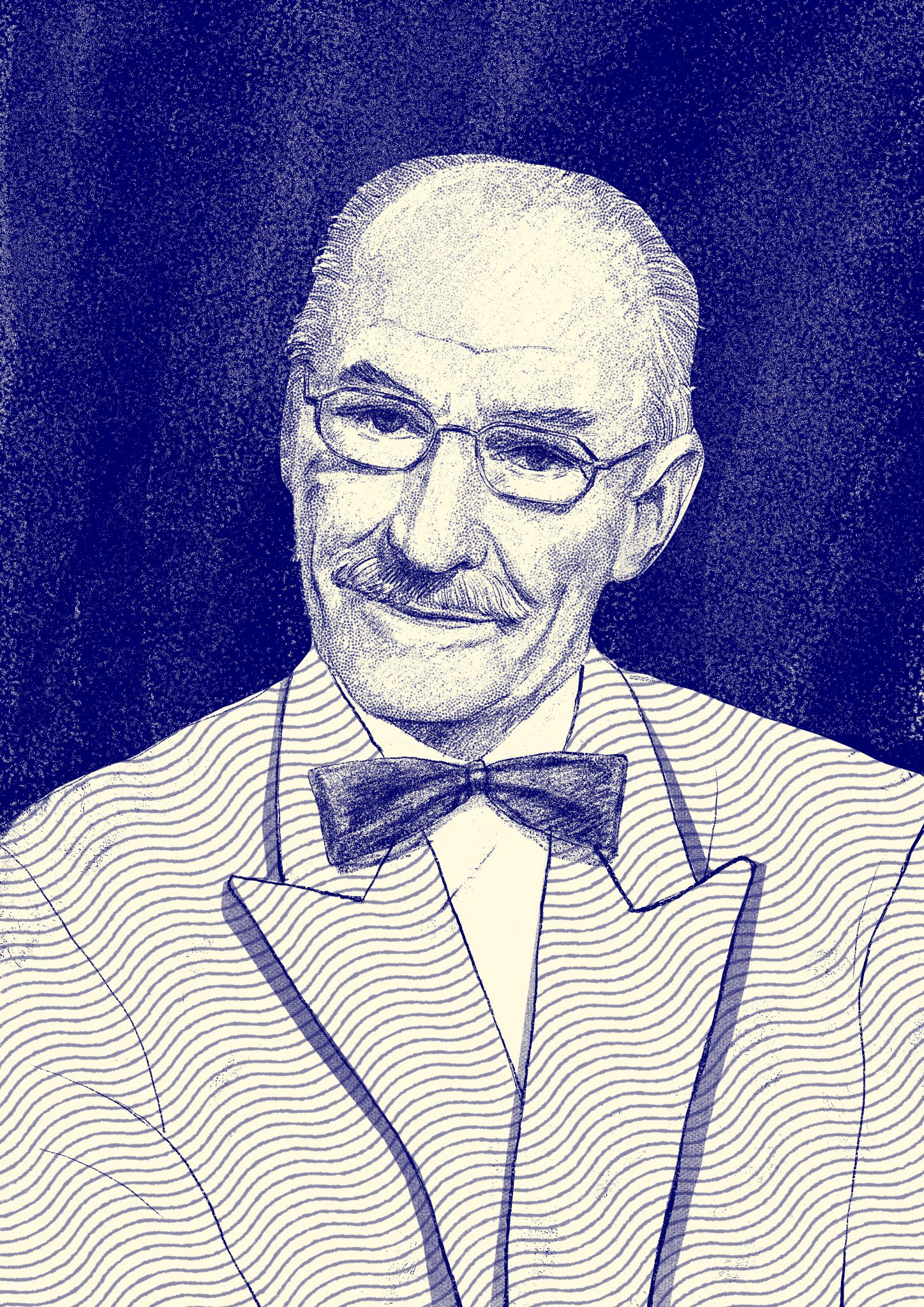

Victor Rebengiuc, an exemplar of long-haul professionalism

Perhaps no other actor had such a strong impact on Romanian cinema – and for six decades no less – as Victor Rebengiuc, who is now honored through a retrospective and a discussion with Cătălin Ştefănescu at this year’s edition of Les Films de Cannes à Bucarest.

From the first roles, which he took on in the early 1960s, and up to the latest appearances, he collaborated with an unparalleled and always surprising openness with all the generations Romanian film has seen over time, from little-known directors to the greatest filmmakers.

His extraordinary availability, lack of histrionics and understanding that performance is not measured in age, experience and fame, but by each role, however small or eccentric, all of this have made him an actor in great demand and loved by successive waves of directors.

That is what always kept him in the game for the most vibrant and valuable opportunities in Romanian cinema, regardless of era and artistic sensibilities. It’s a rare path, maybe even unique.

Of course, his interest in present times and current issues manifested outside theater and film, too: Victor Rebengiuc is an intellectual who has been civically active by taking certain political stances, as well as by addressing some of the most burning topics in the artistic world since the days of the 1989 Revolution and up to the latest interviews.

And he is among the few actors who publicly cast off their compromise roles during the communist era (as he did with The Mace with Three Seels by Constantin Vaeni, where he played Wallachia’s ruler Michael the Brave).

In each of his great roles, one can feel the blending of reflection with intuition, of complete professionalism, which is measured by the ability to cast aside fame and become one with the character and the story, with the delight of acting, which is pushed to the limits.

A pleasure and a curiosity that do not seem to have been altered over his numerous roles, from the young idealists he played early on (led by Apostol Bologa in Liviu Ciulei’s great film Forest of the Hanged) to the unsettling fathers and grandfathers he portrayed in the last few years, passing through the intellectuals full of dilemmas or the slightly ridiculous cynics that populated his midlife career.

It’s admirable how intensely he melts his personality in every character, who assumes their own psychological and emotional being, their own life. And for that, he throws in a variety of means and resources, without falling into mannerism.

Let’s take, for example, three of the key films made in the ’80s: Lucian Pintilie’s Why Are the Bells Ringing, Mitica? (released, as we all know, after the Revolution, as it was forbidden until then), Dan Piţa’s Sand Cliffs and Stere Gulea’s The Moromete Family.

Hard to find three more different protagonists from each other, representatives of various historical and social eras, such as Pampon, with his ridicule à la Caragiale, passed through Pintilie’s filter, the overconfident surgeon, willing to send a young innocent man to prison at all costs, and Ilie Moromete, with his waggish nature and crumbling family (the actor’s initial refusal to play the part of a peasant, on the grounds that he is city-bred, went down in history).

However, there is something that binds the three characters: an implied sense of tragedy, given by the complexity of each of Victor Rebengiuc’s performances (supported, of course, by the script and directing). Behind the masks, there is always a man full of nuances, lights and shadows.

Alex Leo Şerban was right to remark that no matter how many villains he played in his career (and there were plenty; let us remember Tănase Scantiu from Dan Piţa’s adaptation of the same name), Victor Rebengiuc “succeeded in keeping an unaltered source of goodness, which made the villains he played to never come out as monsters.”

Then, it is fascinating how the actor plays the gradual destabilization his characters go through, almost compulsory. From self-control and control over others to insecurity (let’s not forget about the protagonist in The Man in the Overcoat, by Nicolae Mărgineanu) and comic, even grotesque, at times.

Yes, there is something burlesque, in tune with the cinematographic aesthetics of the time, in the characters Victor Rebengiuc played in the first 15 years post-communism, especially in Lucian Pintilie’s films, from the gushy mayor in The Oak to the retired, troubled army officer, pushed by society to commit a crime, in Niki and Flo (one could write a book about the close relationship between the two artists, which manifested through multiple collaborations).

A gallery of characters, especially corrupt officials, representative of a turbulent transition, in which Victor Rebengiuc-the public figure took on, by contrast, positive official roles, such as the rector of the ATF (i.e. Academy of Theater and Film in Bucharest). A position from which he contributed decisively to the reform and modernization of the institution, by introducing new majors and building the film studio in the university yard, and through which he had a positive impact on many young people.

The meeting with the New Wave filmmakers, in the first years of the 2000s, now seems like the most natural thing for this open-minded and change-oriented actor (it is important to stress this point, because very few of the old-generation famous actors accepted to work with the new directors or were cast by them).

With the slightly inadequate, obsolete father’s character in Cigarettes and Coffee, a short film with which Cristi Puiu won the Golden Bear at the Berlin Film Festival, the actor embarks on a series of roles of sweet old men, heartwarming in their attempts to keep up with the new times and win back their family, and who are often overwhelmed by memories. Ion from Medal of Honor (dir. Călin Peter Netze), Costache from The Japanese Dog (dir. Tudor Cristian Jurgiu), and Ulli Winkler from A Love Story, Lindenfeld (dir. Radu Gabrea) are memorable and endearing characters due to their humanity and depth, their dignity with which they live their dramas.

His more recent performances, as well as his roles in the well-known films, which went down into the history of Romanian cinema and are constantly showcased in retrospectives, are easier to evoke, because they are quite vivid in the memory of any given cinephile. But Victor Rebengiuc’s filmography is an intimidating vast one and therefore is worth rediscovering on a regular basis.

Although he had already played in a few films, his breakthrough in cinema came with Forest of the Hanged, and the way he was able to render Apostol Bologa’s troubles, idealism and pangs of conscience became an exemplar of acting, which is invoked all the time. And since then and until the fall of communism, for a quarter-century, the roles have succeeded at an impressive pace as film production has seen significant development as a result of the regime’s politics.

Whether it was B movies or propaganda films (inevitably, Victor Rebengiuc’s career includes such titles, like any other great actor) or films that became classics, present-day or historical dramas, small or main roles (most of them, intellectuals or people in positions of power), his performances stood out in an unusually consistent way thanks to his natural approach.

An intelligent and highly talented actor, an exemplar of long-haul professionalism and respect for the job, as well as of civic consciousness and inner balance, which made him gracefully avoid solemnity, living in an idealized past and the temptation of stepping on a pedestal beyond reach. Victor Rebengiuc exudes an air of closeness and genuineness, whether you see him in a movie, on stage, or in any public appearance.

Journalist and film critic. Curator for some film festivals in Romania. At "Films in Frame" publishes interviews with both young and established filmmakers.