Coming out in June: 5 gems to see at the cinema

It’s official, cinemas are reopening, which gives us the opportunity to come with a bunch of film recommendations. We searched for gems and put together a list, but left out the usual suspects (more precisely, Nomadland, Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn, and Another Round, which are already running in theaters and don’t seem to need any introductions). So we came upon titles showing at One World Romania, or within the F-Sides Film Club, as well as film premieres that have been previously screened at the 2020 Transilvania IFF.

Madre (dir. Rodrigo Sorogoyen)

The newest film by prolific Spanish director Rodrigo Sorogoyen (Stockholm, Riot Police) is a sequel to the 2017 short film of the same name, a one-shot behind closed doors with a mother keeping her child on the phone while his careless father leaves him on an empty beach; as the conversation drags on, with her son thousands of miles from home, it is clear that the kid is lost. In the feature film, Sorogoyen keeps the phone bit, which is pure thriller, and further develops the story into a melodrama. Ten years later, the mother, Elena (Marta Nieto), gripped by melancholy, waits on tables on the same beach where the boy got lost, serving tourists or kids playing around; one of these kids is Jean (Jules Porier), who looks terribly like her missing son. There is something Freudian about their closeness, but it is kept innocent to the end (she feels the need to protect him, he sees in her something that girls his age do not have, and, finally, a maternal figure). I find that the ambiguous nature of their relationship, as well as the missing child story, are the pillars of the film. And one more thing: Alejandro de Pablo’s camerawork, absolutely remarkable, which clings to the characters’ isolation through wide-angle continuous shots.

Coming out in cinemas on June 4, distributed by Transilvania Film.

The Second Mother (dir. Anna Muylaert)

Val (Regina Casé, in an outstanding performance) has been the housekeeper of a traditional bourgeois family in São Paulo for almost a decade and, as can be seen from the first moments, she keeps the place squeaky clean and the family together (as in Alfonso Cuarón’s Rome, there is a fondness in the way she is treated by her employers, but it never transgresses the line between social classes). Just like in Rome, at the end of the day, she retires to her “cell” in the basement and watches TV (one that is covered with doilies), where she lets go of any memories of the family she left behind; sometimes, the youngest member of the family, Fabinho, already a teenager, sneaks into her tiny bed; apparently, he can only fall asleep in Val’s arms. Until the plot is revealed, the story is all too familiar: Val is the humble, invisible person, who keeps an eye on everything so that all is in order – she is a surrogate mother for everyone who seeks comfort. Still, a third person comes into the picture – Val’s daughter, her own kin, who applies to college, to Architecture. But Jessica doesn’t care about the class differences, it’s all nonsense to her (she sits at the masters’ table, bathes in their pool, sleeps in the guest room, to her mother’s horror). “I don’t know who this girl is”, says Val, pretending to water the flowers, holding the gardener’s ladder, while they both spy on her: “Pretend to mow the grass; get a better look, what is she doing? Is she reading?”

Forget about the dull films depicting the class struggle, all stuck in ideology, in Muylaert’s film, everything flows into a situation comedy: Val is on her masters’ side in this conflict and sees them as her only family, although, she, herself, wouldn’t dare for a moment to break the rules (it’s a long way to her awakening). In my favorite scene, the protagonist, after keeping her head down all her life, gets in the nearly empty pool, on the grounds that there has been a rat invasion; she’s so ecstatic that she begins laughing out loud.

The Second Mother can be seen within the F-Sides Film Club on Wednesday, June 2.

Maso and Miso Go Boating + S.C.U.M Manifesto 1967

Watching these films, which are part of the Delphine Seyrig retrospective at OWR (“The Extraordinary Adventures of Delphine in the Land of Feminism”), I remembered the words of Agnès Varda in The Beaches of Agnès: “I tried to be a joyful feminist, but I was very angry.”

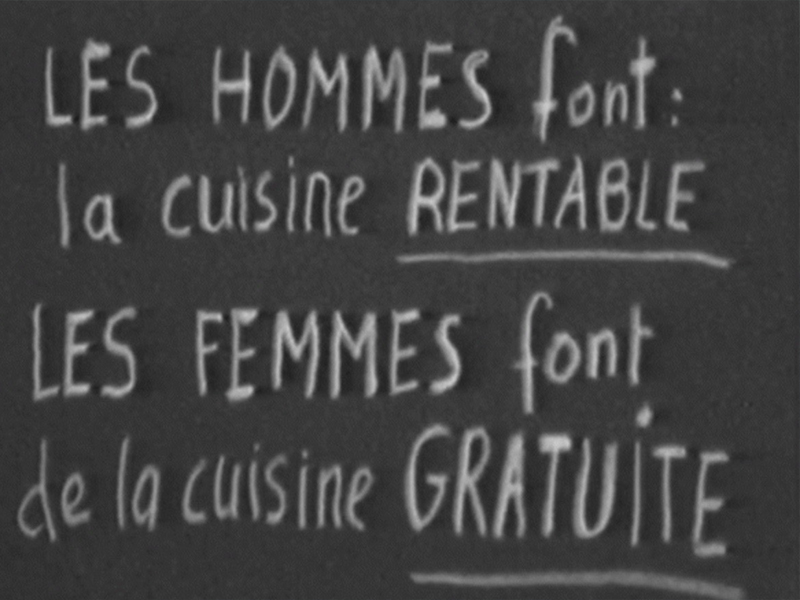

The United Nations designated 1975 as the “International Women’s Year” – on one of the episodes of the French TV show Apostrophes, its host Bernard Pivot invited Françoise Giroud, the secretary of state for women’s issues, to comment on all sorts of misogynistic remarks that were meant to provoke her. The broadcast, a total fiasco, felt like a bit meant to misrepresent women from the start (the title translated as a breath of fresh air for men who apparently were persecuted by feminists). Despite the silent promise, the only female voice there, Giroud, does nothing but indulge in the game of the men on the set (she laughs at their jokes, pats them on the shoulder, says she has never met a misogynist in her life, that domestic violence is just a love kink; she sits with her legs crosses, acting all casual, while men explain the futility of women in every field). Pivot, himself, claims he is not a misogynist since he has so many women behind the camera (4 camera operators and the director, so what if there are only men in the spotlight?).

The Disobedient Muses (Les Insoumuses, aka the group of filmmakers Carole Roussopoulos, Delphine Seyrig, Ioana Wieder, and Nadja Ringart, pillars of feminist activism in the 1960s French cinema) comment on the show’s recording, exploiting the material in various ways (they draw attention on the outrageous statements by marking them with intertitles or repeating the moment several times, they mock them by inserting applause or whistle effects, etc; the sky is the limit); the idea is for this material not to survive time without receiving a mild response. At the other end, SCUM Manifesto (Society for Cutting Up Men) is the vitriolic response, where Delphine Seyrig reads the 1967 manifesto by Valerie Solanas, who was no longer printed in France, out loud: among other things, “the male is a biological accident, a walking abortion”.

The two films can be seen at One World Romania on Saturday, June 19.

The Certainty of Probabilities (dir. Raluca Durbacă)

The manifesto brings me to the next film – in 1968, Valerie Solanas shot Andy Warhol. Street riots broke out in France. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. During this era of mass protest and effervescence, there was a sense of political liberalization in the air (let us recall the Prague Spring in Czechoslovakia, a liberal reform program in a strong attempt to distance itself from the Kremlin). What about Romania, what happened here? Lucian Pintilie’s The Reenactment was made that year, but this is not what this is about. With her debut film, The Certainty of Probabilities, Raluca Durbacă aims for a far-reaching editing project, reassembling the archives of the Sahia studios – is there any depiction of 1968 in the local media? What does that say about us? At first glance, we were recluses, happy in our economic growth (we were friends with Vietnam, friends with progressive Czechoslovakia), and our contact with the outside world hardly mattered. In our world, everything was running smoothly (an impressive part of the montage consists of numbers and statistics running obsessively on TV). It’s hard to say what it was like beyond this facade, – although it’s clear that people seemed to have somewhat of an ideal life – drawing a parallel between the way we are used to perceiving the year 1968 and what it looks like in our archives is quite intriguing. Did Romanian people know what was happening in the world in the year tourists would come to delight themselves with traditional Romanian food?

The Certainty of Probabilities screens at One World Romania, on Monday, June 14, and on Wednesday, June 16.

My Mexican Bretzel (dir. Nuria Giménez)

I’m not sure if I should say it or not. It’s impossible to talk about Nuria Giménez’s film without divulging the anecdote: it’s a wonderful pseudo-documentary, a red herring, if you will, which is somewhere in the avant-garde found footage area. Giménez came across some home movies shot by her grandfather between 1940-1960 – amateur films made with a certain aesthetic eye, showing mostly her grandmother – testimonies of their life together, especially their extravagant trips across Europe. While going through the footage, she wrote a completely fictional story, synchronized with the images, an intimate diary of the female character, who presumably lives a double life, dreams of a Mexican man, but never finds the courage to leave her marriage. In the diary, she recounts both her secret feelings and her discoveries (among other things, a volume of inspirational quotes on life, published in 1919 by a certain guru Paravadin Kanvar Kharjappali, a complete fabrication). The image and the sound are out of sync, there is hardly any sounds throughout the film, but when the silence breaks, it’s just generic noise (a train, a soft rustling, heels on the pavement); the diary is not narrated by a voice-over, but it appears on screen, in the form of subtitles. If at first, you might think that the sound artifice is related to a diegetic detail revealed very early in the film (that is, her husband had a plane crash and has hearing problems), Giménez steps in later to give a clue about the fact that there are actually two divergent stories. Due to this artifice, the film requires two viewings – one, in which you let yourself be carried away by the fictional story, and another, in which you rather follow the audiovisual tricks she used in making the film. In the end, we’re left with these questions: Is this film less real because it includes an untrue story laid over real images? Don’t we all create fiction when we talk about our childhoods on video?

My Mexican Bretzel screens at One World Romania on Saturday, June 12.

Journalist and film critic, with a master's degree in film critics. Collaborates with Scena9, Acoperișul de Sticlă, FILM and FILM Menu magazines. For Films in Frame, she brings the monthly top of films and writes the monthly editorial Panorama, published on a Thursday. In her spare time, she retires in the woods where she pictures other possible lives and flying foxes.