Top films awarded with the Palme d’Or

As there is only a week left until the 76th edition of the Cannes Film Festival (May 16-28), we looked into the archive of films that have been awarded the Palme d’Or, the most prestigious prize in the competition, and we’ve selected some of the most beloved winning titles. With a reputation higher than the Oscar for Best Picture – with which it has aligned only twice in its 75-year history – the Palme d’Or archive includes revolutionary films, as well as eccentric and reprehensible titles, but all have one thing in common: they always stir up a lot of anticipation and interest among audiences worldwide.

Therefore, below is a subjective – and certainly incomplete – selection, made by the FiF team, of benchmark films, to be seen and revisited anytime, or, as one of our colleagues has pointed out, that deserve to be felt.

P.S. We hope it will sweeten the bitter taste of this edition without Romanian films in competition.

4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days (Cristian Mungiu, 2007)

I recently had the opportunity to revisit 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days after several years. I watched it at the Cinematheque in Oslo where they screened a film print preserved by the Norwegian Archive. I found that the film is still very solid, exactly 16 years after winning the Palme d’Or. What struck me most during this viewing, more than any other, was that I didn’t feel like I was watching a reconstruction of an era (the end of the terrible ’80s). Of course, the relatively short time between when the film was shot (the mid-2000s) and the setting of the story meant that some of the exterior and interior locations in Bucharest did not require major set design or post-production work. But I think that this feeling is due to the script (a dramatic event concentrated in just a few hours), the direction (especially the long takes, filled with tension), the acting (Anamaria Marinca is simply brilliant), and the anti-glossy cinematography, which very much pulverize the artificial inherent in any film set in the past. (Ionuţ Mareş)

Taste of Cherry (Abbas Kiarostami, 1997)

I couldn’t find a more appropriate way to recommend this superb film than through a reinterpreted line, in verse of course, as only Kiarostami‘s films manage to convey – watching them, you feel like you’ve lived a poem.

If you look at the four seasons,

each season brings fruit.

In summer, there’s fruit,

in autumn, too.

Winter brings different fruit and spring, too.

No mother can fill her fridge with such a variety of fruit for her children.

No mother can do as much for her children as God does for His creatures.

You want to refuse all that?

You want to give it all up?

You want to give up the taste of cherries?

(Anca Vancu)

Wild at Heart (David Lynch, 1990)

An impossible answer to an impossible question – far too many Palme d’Or-winning films are paramount in both the grand canon and in my personal one, from Brief Encounter, Roma, Citta Aperta, and The Third Man, going through Viridiana and The Leopard, the vast majority of winners from the sixties, seventies, and nineties, right up to Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives, and I’m sure I’m leaving some titles out – so I will deliberately focus on one of the most irreverent titles to have taken home the golden palm frond of the Croisette: David Lynch’s Wild at Heart.

Ultimately, it’s one of the summation films of the nineties: this road movie that turns the nostalgic Americana dream upside down (see Paris, Texas as a counterpoint) at the end of the Reagan era, a death and rebirth certificate written (for the big screen) in a flash. A dream Lynch deconstructs until he reaches the very heart of darkness, its most violent and psychosexual impulses: an intention announced from the bloody and explicit murder depicted in the very first minutes. This is the gamut of the great American filmmaker, one of the last truly great ones, as well as the gamut of American culture (i.e. the hegemonic culture of cinema) through which he saw so clearly – see the incredible scene on the dance floor, between black metal and Elvis, followed by the superb scene that propelled Wicked Game among the defining songs of the decade. And this clarity translates into a fusion between the darkest nightmares (Willem Dafoe, a true sleep paralysis demon with bad teeth and stockings over his face) and the lightest dreams (any love scene between Sailor and Lula, among the most beautiful in the history of cinema). And with one final question that will always remain open: Is there salvation from the eternal cycle of violence? With the blessing given under the dual guise of Sheryl Lee – Glinda the Good Witch and Laura Palmer – all we really know is that love is the only thing that can put a stop to this scorched and bloody road. (Flavia Dima)

Fahrenheit 9/11 (Michael Moore, 2004)

I haven’t seen all the Palme d’Or winning films, but looking at the ones I’ve seen, two are very important to me. Because rules are rules, I’m going to choose Fahrenheit 9/11 – Michael Moore’s 2004 documentary about George W. Bush’s presidency, from the fraudulent way he won the election, his family’s relationships with the Bin Laden family to the Iraq War. I recently re-watched it and felt the same pit in my stomach and repulsion at the greed, hypocrisy, and arrogance that people can have. A film that is just as important and relevant today as it was (almost) 20 years ago, which shows that American politicians (and leaders) are no different from Russian ones (whom we all despise, especially since they started the war in Ukraine) and that the world is not and will never be a safe place as long as the politics of the major powers are dominated by hypocritical and power-hungry tyrants. I wholeheartedly recommend it. Regardless of your taste in movies, I bet this one will keep you glued to the screen and open up new perspectives.

I’ll end by mentioning the second title on my list, for the more curious (and cinephiles) among you – Parasite (Bong Joon Ho, 2019), a film I bet most of you have heard of, a masterpiece for countless reasons, which if I were to list them all, there wouldn’t be any room left for my colleagues. So I’ll stick to the most important one: I felt such visceral pleasure watching this film like I hadn’t in a long time. It was simply refreshing & mindblowing. (Laura Mușat)

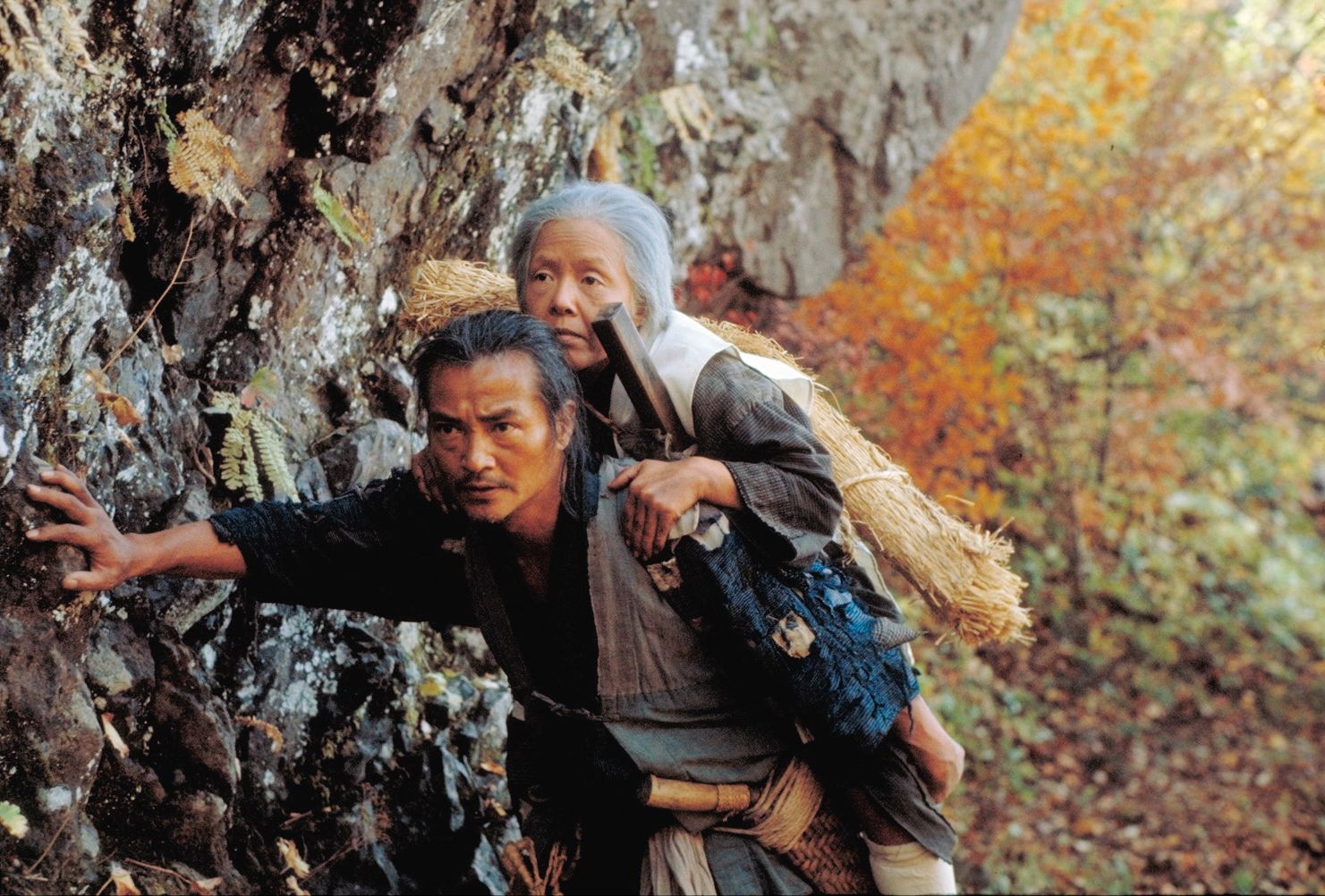

The Ballad of Narayama (Shōhei Imamura, 1983)

For Shōhei Imamura, there was always only one topic to explore in film: the barbarism hidden within humanity. With The Ballad of Narayama (Narayama bushikô), set in an isolated village in 19th-century Japan, this master of subversion achieves the opposite of a nostalgic representation: a film in which all deviations – from zoophilia to the ordinary of death – conveniently line up with the alibi of history and create a possible documentary dedicated to a rabid human species. Only this species is precisely the demographic pool with which Imamura populated his films: from pornographers to serial killers, his oeuvre testifies to the perversions of a post-war society where everything seems to sound too good while the underground seethes with radical sensitivities. Both a step to the side – it’s a historical film – and an obvious confrontation with his constant obsession with the unconventional, The Ballad of Narayama is another sample of narrative versatility and love for filmmaking from a storyteller who is as slippery as he is underrated. I cannot stress enough: Shōhei Imamura’s films all urgently need to be (re)discovered. (Victor Morozov)

The Tree of Life (Terrence Malick, 2011)

It’s not uncommon for Cannes juries and their choices to spark rumors and gossip. That a masterpiece like Carol could have won the coveted trophy in 2015, but Xavier Dolan objected to it; or that an important film like 120 BPM could have come out victorious two years later, but was opposed by Will Smith— mostly unfortunate events. But, from time to time, the stars do align: as in 2011, when, following Lars von Trier’s anti-Semitic comments, the jury decided to distinguish that year’s favorite, Melancholia, only with an acting award (for Kirsten Dunst), and award the top prize to The Tree of Life. Not that von Trier’s film didn’t deserve the Palme d’Or almost as much, but there is just something truly unique about Terrence Malick’s masterpiece. More than a film, it’s a meditative, almost religious, phantasmagorical experience. The first hour, in which Malick juxtaposes seemingly insignificant aspects of everyday life (from trees and water to curtains blowing in the wind and children running after a fumigation car, all shot with divine grace by Emmanuel Lubezki) with the coldness of the infinite universe, whose birth we witness, is perfect. The last twenty minutes, which depict a possible afterlife and are among the most beautiful images ever captured on film, are a true miracle. It is a film of rare beauty, perfect in all its imperfections, which should/deserves to be felt rather than merely watched. Unless you love (it), your life will flash by. (Laurențiu Paraschiv)

An article written by the magazine's team