Watercooler Wednesdays: Beef

Watercooler Shows, the trending series that everyone talks about the next day at the office, around the water cooler. Watercooler Wednesdays seeks to be a (critical) guide through the VoD maze: from masterpiece series to guilty pleasures, and from blockbusters that keep you on the edge of your couch to hidden gems; if it leads to binging, then it’s exactly what we’re looking for.

Beef (Lee Sung Jin, 2023)

The trailer and premise of the latest Netflix hit stuck to me like a bug splashed on the windshield: a minor traffic incident, where both drivers are clinging to their own sense of justice (foot on the gas pedal and giving the finger on the window), turns into an out-of-control race towards a personal abyss.

My only reluctance, which quickly dissipated, was about Ali Wong’s acting skills – one of the two “traffic hellraisers” alongside Steven Yeun – rather known as a stand-up comedian (one can’t help but notice that her stand-up persona is exactly that driver you wouldn’t want to honk at). Ultimately, what keeps Beef afloat, under all the weight of its own stylistic ambitions, is precisely the main actors’ versatility to keep the drama alive.

When I say afloat, it doesn’t mean that Beef is mediocre, and when I say stylistic ambitions, it doesn’t mean that they aren’t achieved (most of the time). Unfortunately, that’s all they are: style, gimmicks, well-executed ideas, twists, brilliant moments (comically, visually, subtle social commentary, etc.), whose presence indicates an artsy product and nothing more.

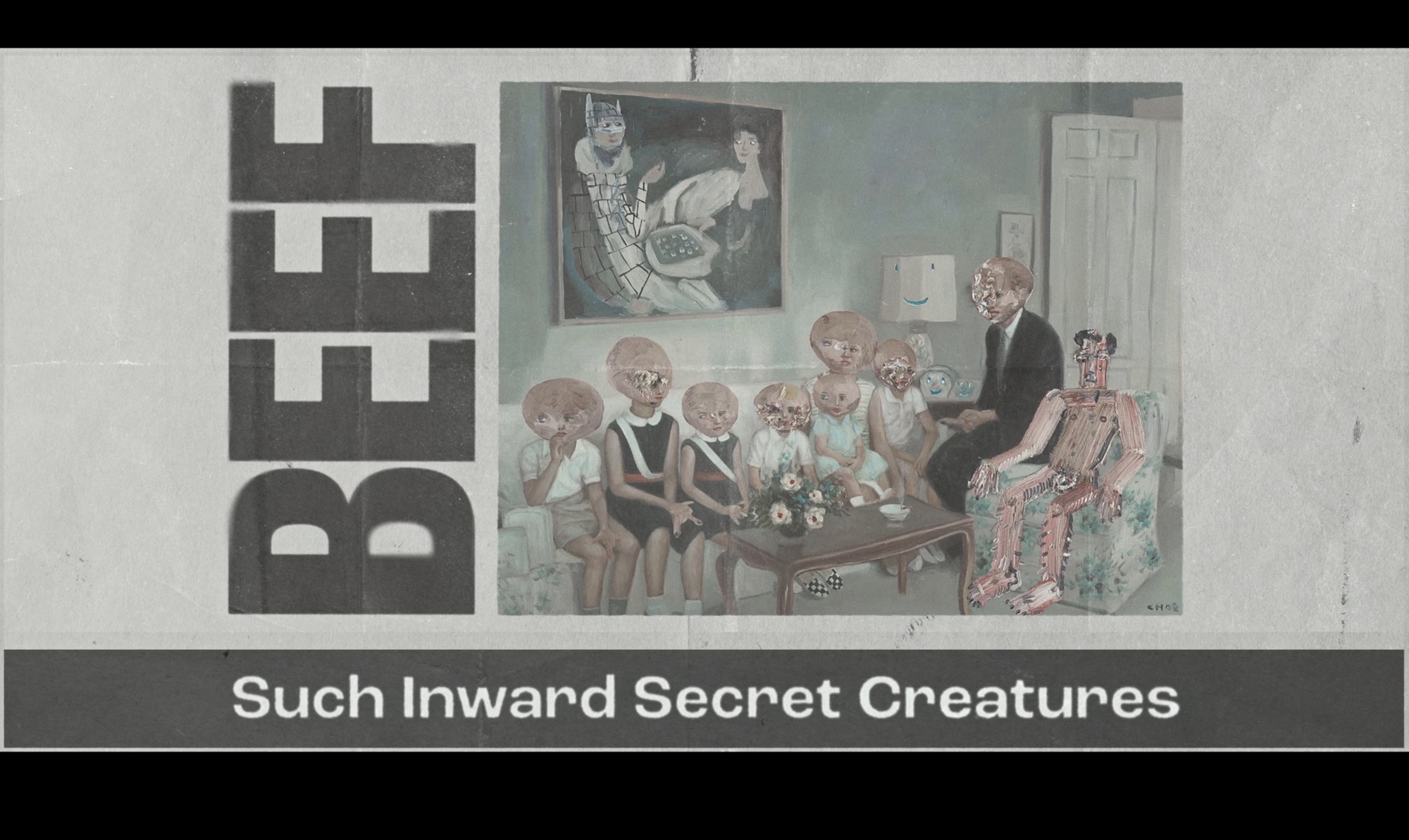

The best example is the paintings that open each episode, which ended up in this role fortuitously, after one of the supporting actors (artist David Choe) gave the director carte blanche to choose what he wanted from his oeuvre. Over them, displayed in various carefully selected fonts, appears the title of the series spread across the entire screen – a watermark pasted over the poster of art gallery caliber, which, in turn, appears like a static frame in each episode. It’s a great, memorable opening title – a solid practice in the new golden age of television – but the layers are juxtaposed in the vein of a palimpsest (with the music coming on top of all of them.) They work by overlapping and appropriation of high art; the show’s title is then replace by the episode title, carefully selected quotes (from Herzog and Bergman to Sylvia Plath and Kafka), shiny keychains that lend their value not just through their deep meaning, but also through the original author’s signature (Beef is too smart put the signature on display, but there will always be a Netflix article on hand to signal the prestige.)

Choe’s neurotic way of painting, and whose “artworks” could very well pass as illustrations in a handbook of mental disorders (where road rage should fit in perfectly), seems to be the best introduction into the topic. The self-made woman white SUV and handyman red truck (the anti-heroes Amy and Danny) have long been in freefall – their car scuffle, unleashed in the supermarket parking lot, is ultimately just a new opportunity for self-destruction. Each of them seeks help in their own way: she goes to therapy (dragged by her husband, an annoying monument of positive thinking), he goes to church (rather to pocket some money from renovation)… fake it till you make it, and for a while, things seem to go well. They both subscribe to a behavioural pattern resembling that of a magnet: Amy tends to push everyone away, thinking she’s a rotten apple that will destroy her family, Danny wants to keep everyone close, thinking he’s not good enough without them. Script-wise, this symmetry remains an admirable achievement, despite the far-fetched escalations on both sides: from honking and graffiti on the car, it gets to kidnappings and armed robberies, each of them involuntarily dragging their family into this conflict.

Another thing they have in common is the fact they are children of Asian immigrants: caught between the old world and the new world, not truly belonging to either, eager to fit in or, on the contrary, to put up all kinds of barriers between us and them, being under constant pressure to be successful and not waste their parents’ sacrifices. Of course, everything runs in the family – although lazy and predictable, the throwback moment, where we visit the protagonists in their childhood, is quite moving. Beef handles the “predetermined fate” bit quite well, balancing that moment of early fear and wrongly integrated lessons with moments of unconditional love. As I said, the well-played drama holds things together, even when the script sabotages it.

Beef is just as much a (tragic) comedy – and the best moments are precisely those of psychological breakthrough, when the characters stare into the abyss and the abyss blinks back at them: Amy, a petite figure, waving a huge revolver as if she wanted to shoot Danny through the phone, or Danny’s highly elaborate plan to commit suicide by use of hibachi grills (which he buys and keeps returning to the supermarket), a sign of respect for his culture, which obviously no one would have noticed.

Also, as subtle as it is, the social commentary and satire on the West-East divide is worth watching. From intra-Asian racism and all sorts of hints – Amy (Chinese-Vietnamese) subtly tells her husband that Danny (Korean) had a bad reaction when he found out her husband was Japanese – to the power relations with the white people in their lives, of whom they both earn their living, Beef juggles so many things that it’s impossible not to get hooked by at least some of them.

Beef is available on Netflix.

Film critic and journalist, UNATC graduate. Andrei Sendrea wrote for LiterNet, Gândul, FILM and Film Menu, and worked as an editor on the "Ca-n Filme" TV Show. In his free time, he works on his collection of movie stills, which he organizes into idiosyncratic categories. At Films in Frame, he writes the Watercooler Wednesdays column - the monthly top of TV shows/series.