Watercooler Wednesdays: The White Lotus & Black Summer

Watercooler Shows, the trending series that everyone talks about the next day at the office, around the water cooler… today there are no longer offices to go to, the movie theaters are functioning at limited capacity, and the content on the streaming platforms is increasing exponentially. Watercooler Wednesdays seeks to be a (critical) guide through the VoD maze: from masterpiece series to guilty pleasures, and from blockbusters that keep you on the edge of your couch to hidden gems; if it leads to binging, then it’s exactly what we’re looking for.

The White Lotus (Mike White, 2021)

I binged the HBO miniseries about the guests and employees of a luxury hotel in Hawaii in two different stages. After the first 3 episodes, I was fully hooked on its humor – sometimes a little too close to an American Pie-type comedy, sometimes at the upper limit of what would be called “bad acting”. Over the next three episodes, as the situations set in the first half were working on their dramatic outcomes, The White Lotus seemed to have exhausted all its momentum in some screenwriting decisions that made no sense. In the end, though, the bitter conclusion I left the Hawaiian paradise with is that The White Lotus may not be one of the greatest series released this year, but it’s certainly one of the most clever.

The series begins in a somewhat Chekhovian key – not with a rifle that must be used until the end, but directly with the end and the result of the shooting: a coffin loaded onto an Air Hawaii plane. It’s a narrative gimmick, a flashforward that sets the tone for the kind of satire and caustic humor that infiltrates the tropical paradise at every turn: “We heard somebody was killed at the White Lotus … Well other than that, did you have a good vacation?”

The coffin at the end also works as a cunning disclaimer to camouflage an unbelievable (though extremely aesthetically pleasing) narrative twist, but quite essential in rounding out the director’s vision. Without this “heads up” scene, the fatal incident at the end would simply seem out of place. With this scene, the viewer is invited to follow the clues like in a detective movie, but then they fall numb to a tropical languor where nothing actually happens, so by the end, they’re all jacked up on anxiety as the vacation comes to an end and not only there’s no rifle to be seen hanging somewhere, but the number of potential casualties continues to rise. So let’s meet the characters.

The White Lotus‘ guests are the exponents of the infamous 1%, each with its own story of getting rich, but all, without exception, white (but not just white, white with shades of WASP). Skillfully relying on its own premise, the script introduces them one by one, with name and surname, as they are welcomed by the hotel employees (we only know their first name, a telling sign) for the high-class pampering treatment of their choice.

The Mossbacher family made a fortune in the tech industry. In fact, she is the money-making machine – and continues to do so, even on vacation – which obviously undermines his masculinity. Driven by a medical scare and a few revelations about his own father, Mark Mossbacher focuses his energy on his teenage son, a screen addict and an eligible candidate for the Incel culture. The family is completed by the elder daughter, Olivia, always ready to repudiate her white and rich parents, as long as she doesn’t have to give up on the inherited privileges – among them, the possibility to bring on holiday a friend of color who validates her as being on the good side of the class war.

Then we have the couple on their honeymoon, the rich boy and the poor journalist, still unaccustomed to luxury, who goes through her final streak of independence before becoming the trophy wife, the ever-present host of charity dinners. “And what’s wrong with that? A trophy shines, it’s a source of pride, a trophy is made of gold”, she is told by her mother-in-law, who comes for a few days/episodes as a honeymoon crasher after her son complained that the hotel had accommodated them in a less luxurious apartment. The apartment mix-up is what ultimately triggers the domino effect that leads to setting off the Chekhovian device.

Tanya McQuoid is probably the richest of them all, but also a piece of emotional baggage that she literally carries with her: the urn with the ashes of an abusive mother from whom she fails to separate. Excellently played by Jennifer Coolidge (rather known in pop culture as Stifler’s Mom), the character seems the most out of touch with reality of all the rich folks inhabiting the hotel, but also the most honest when it comes to recognizing the transactional nature of interpersonal relationships between those who have and those who don’t. And with that, we come to “what the author meant”.

The author here being Mike White – essentially a screenwriter, occasionally an actor, a 3 times director, and a Survivor finalist. If you look through his filmography, you might think that it gives out two different careers. White wrote Nacho Libre and School of Rock, both for Jack Black, and shared a Golden Raspberry with two other screenwriters for The Emoji Movie disaster. On the other hand, White has won several Independent Spirit Awards, and his films premiered at Sundance and Toronto. This eclecticism is fully reflected in the type of comedy we see in The White Lotus.

On the one hand, we have the ideological wars with the incisive retorts, held at dinner by the Mossbacher family, or the front high standards the resort manager, Armond, is so strict about, whose unraveling requires a bit more general knowledge (tropical kabuki, for example, to describe the way hotel employees must keep a vague, interchangeable presence, hiding behind a smiling mask). Other times, the series easily resembles a family sitcom, with silly jokes deriving from the acronym BLM (Bureau of Land Management), and the next thing you know, out of nowhere, it turns into a typical R-rated teen comedy. The red thread that connects all these comic situations is the constant feeling of awkwardness to which White subjects his characters. Slowly, this awkwardness is perceived by the viewer, too; it’s all laughs and fun, but you also want to look away, so that the character can get out of the embarrassing situation with a shred of dignity.

Structurally speaking, the problem that this kind of humor creates is that it makes empathy considerably more difficult. White’s comedy, in whatever form it may come, hits a home run in the first half of the series. It’s so good that when the characters come and ask you for a human reaction to their more or less important dramas, you couldn’t care less. Which begs the question: Is it a failure (a dramedy, where the drama is sabotaged by the use of too much comedy), or is it a success, because that’s what White wanted to show all along? The series was hailed as a social satire of the privileges of rich whites. Which it is, but that’s only half the truth. The other half, which is the source of the viewer’s awkwardness, is that at the end of the vacation, we are not offered any of the aesthetic solutions we are used to: there’s no happy end, no uplifting tragedy, and no cynical commentary on human nature. The rich people do not prevail through devices and corruption, but because they have done nothing wrong (and ultimately gain nothing, only a deferral of existential crisis). The hotel employees resume their routine and their fake smiles for the new group of VIP tourists. And those who were in the lobby – and who stumbled upon the chance of becoming privileged, they just had to grab it – return to the womb after minor mutiny, followed by small compromises (you can’t even hate them for them).

The White Lotus is available on HBO GO.

Black Summer 1 & 2 (John Hyams, Karl Schaefer, 2019 – 2021)

There is a certain type of cinema that manages to deliver at the same time, from the first second, the promise, but also the confirmation, that you made the right choice. It is more common with genre films, which offer more ground for staggering openings – an excellent example would be the horror film It Follows – and often enough with short films, where the limited format pushes for creativity. After all, it’s about how you tell the story and not the subject itself, but obviously not every startling beginning has the same ability to anchor the viewer in the fiction that is presented to them.

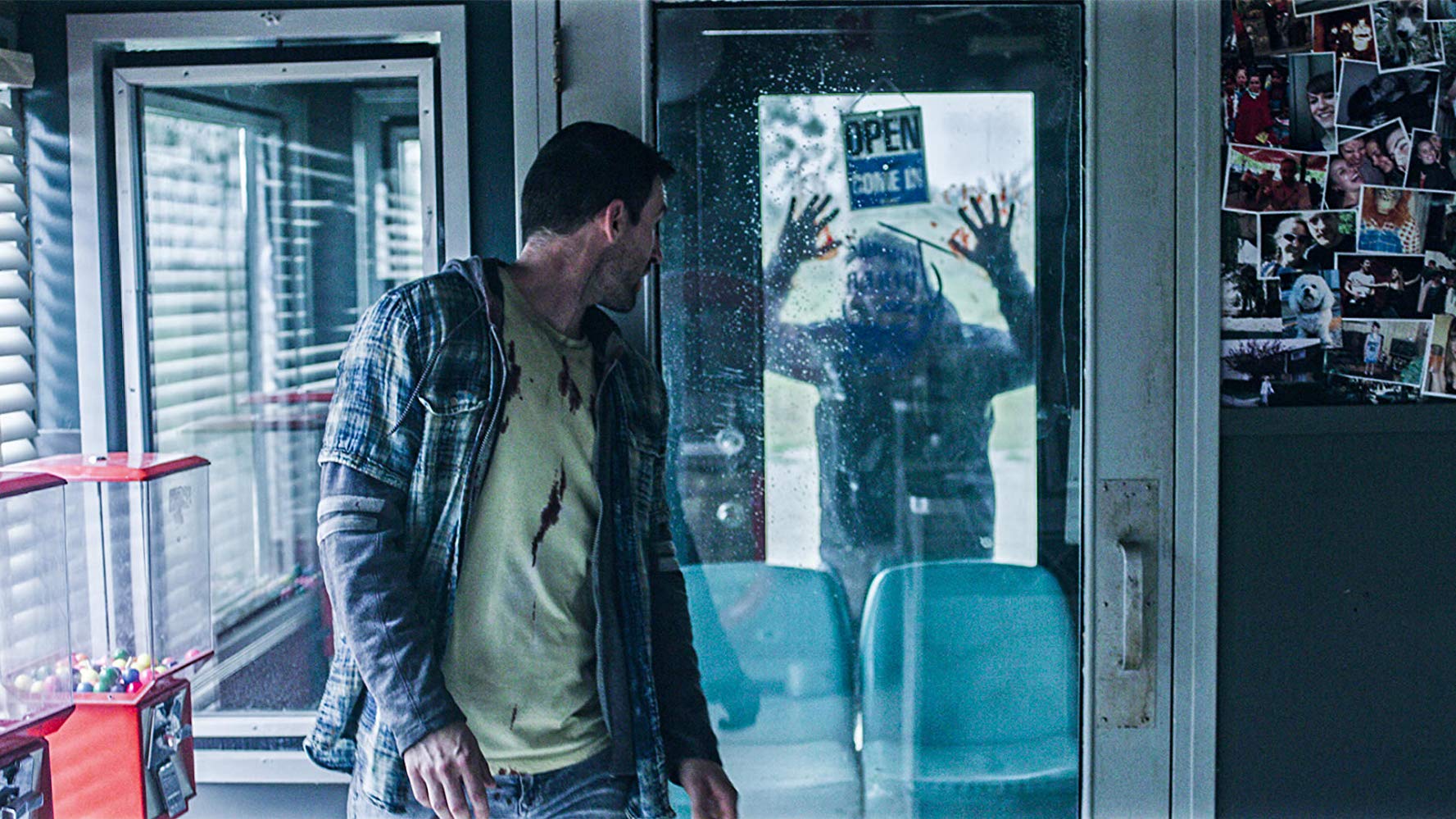

The zombie apocalypse that is Black Summer is one of those movies, where the best of cinema (in terms of spectacle) is refined every second and any overexplicit deadweight was cut in editing: you are practically invited to get in a car in motion, which accelerated from 0 to 100 km/h before you even got to make acquaintance with the story. Here, the car in motion is actually a car in motion… and I have to admit that I jumped right in without looking. It was only after finishing season 2 that I realised I had skipped the pilot episode. A review is a discussion on the virtues and shortcomings of a film, but it’s also the retelling of an experience: Black Summer (season 1) is worth seeing in its entirety, but it’s a little better when you start from episode 2.

The hand that turns the steering wheel, bruised and full of someone else’s blood, is that of a Hispanic. On the right, an Asian woman looks at him tensely, waiting for the next move. In the back seat, a white upper-class old woman bounces her eyes around between the two, trying to establish an alliance between women, just in case. Feeling their gaze, the man starts talking, presents himself, so to speak, but does so according to the unwritten laws of a reality we do not understand but we intuit that it has erased any trace of social contract: “Hey… I’m not gonna rape you! I’m one of the good guys.”

Season 1 of Black Summer got me hooked from the first minute, and this introductory scene is a textbook on dramatic and aesthetic efficiency that the directors will replicate almost perfectly in all episodes. We learn the rules on the go, along with the characters, the only difference is that they don’t have time to learn from their own mistakes.

Rule number one: run.

Rule number two: in a zombie apocalypse there are no heroes, only survivors, and resources are limited.

Rule number three: do not talk to strangers; even if they don’t want anything from you (water, food, clothes, shelter, car, fuel), they are very likely going to kill you out of fear you’ll kill them first.

Rule number four: if you met a stranger who wanted to kill you and steal your resources but now you’re both being chased by zombies, form an alliance.

Rule number five: if someone in your group dies for any reason other than a zombie bite, run.

Anyone who dies in Black Summer turns into a zombie, this is the only creative license that the series can afford for the canon. It’s a well-thought gimmick that offers almost unlimited creative ammo to develop and solve tense situations in unexpected ways.

Black Summer rises above other similar productions because it constantly tunes its dramaturgical and audiovisual instruments to these very simple premises. In a ruined society, the camera can only follow one individual perspective (mostly making use of POVs). There is no plan, there is no explanation, no one even knows how it all started. There are only rumors traveling around, and the other’s intentions are never clear until they choose to act.

What we see and hear is what the character we are watching at that moment sees and hears. From this point of view, Black Summer rigorously slides into a conceptually minimalist aesthetic, but extremely offering visually. We are always with our character, but we don’t follow them with the eternal “camera breathing down their neck”. Despite all its limitations, Black Summer always finds resources in the film’s grammar – editing techniques and camera movements, including long takes non-specific to the genre – to keep up with the kinetic explosion of those who want to survive and nothing more.

Black Summer takes this approach from the grassroots – a living dead running on the lawn in the suburbs, what could be closer to the core of the genre? – but it’s not a video or just zombie art for the sake of art (or for the sake of zombies). Precisely because it doesn’t seek to prove anything about humanity or to wrap its protagonists in elaborate life scenarios (what life?), scientific explanations (who cares anymore?), or romantic subplots (there’s no time for that), the series offers more consistency than the average of the genre when it comes to the psychological depth of the characters. The decisions that the characters make are based on a continuous negotiation (between them and with their own conscience) of what is human and of what comes as an acceptable rule to found a new social contract. It’s a sphere that grows smaller as it becomes clear that it’s only a matter of time before the human race goes extinct and that chivalry is long gone.

Season 2 of Black Summer remains somewhat true to the minimalist rigor but bets more than necessary on the strengths I mentioned above. In other words, after achieving excellent results on the principle of less is more, the creators switched to the motto more of less is more. More people fighting for resources, more separate and chronologically dislocated narratives, more intent on camera artistry. Spectacle-wise, the result is a balanced one: when it hits the target, Black Summer 2 hits a bull’s eye. Script-wise, season 2 is disappointing, and not just by comparison.

The series is available on Netflix.

Film critic and journalist, UNATC graduate. Andrei Sendrea wrote for LiterNet, Gândul, FILM and Film Menu, and worked as an editor on the "Ca-n Filme" TV Show. In his free time, he works on his collection of movie stills, which he organizes into idiosyncratic categories. At Films in Frame, he writes the Watercooler Wednesdays column - the monthly top of TV shows/series.