Watercooler Wednesdays: Irma Vep & Stranger Things

Watercooler Shows, the trending series that everyone talks about the next day at the office, around the water cooler. Watercooler Wednesdays seeks to be a (critical) guide through the VoD maze: from masterpiece series to guilty pleasures, and from blockbusters that keep you on the edge of your couch to hidden gems; if it leads to binging, then it’s exactly what we’re looking for.

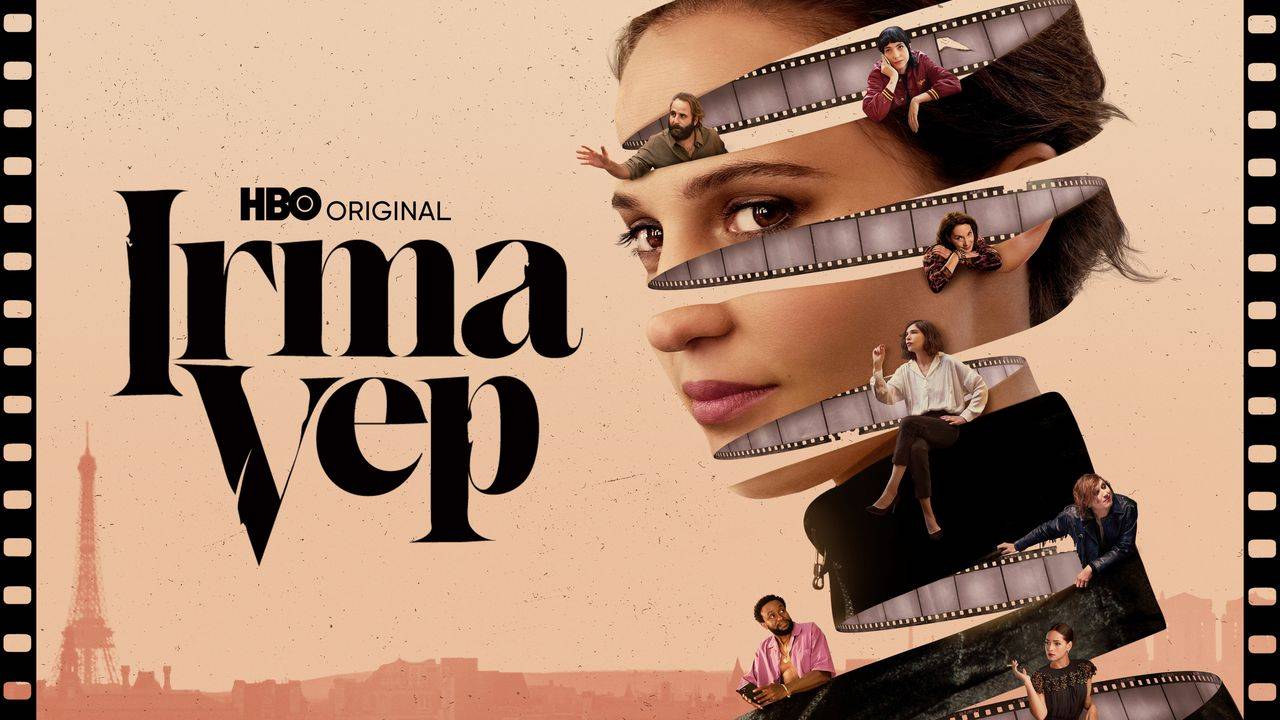

Irma Vep (Olivier Assayas, 2022)

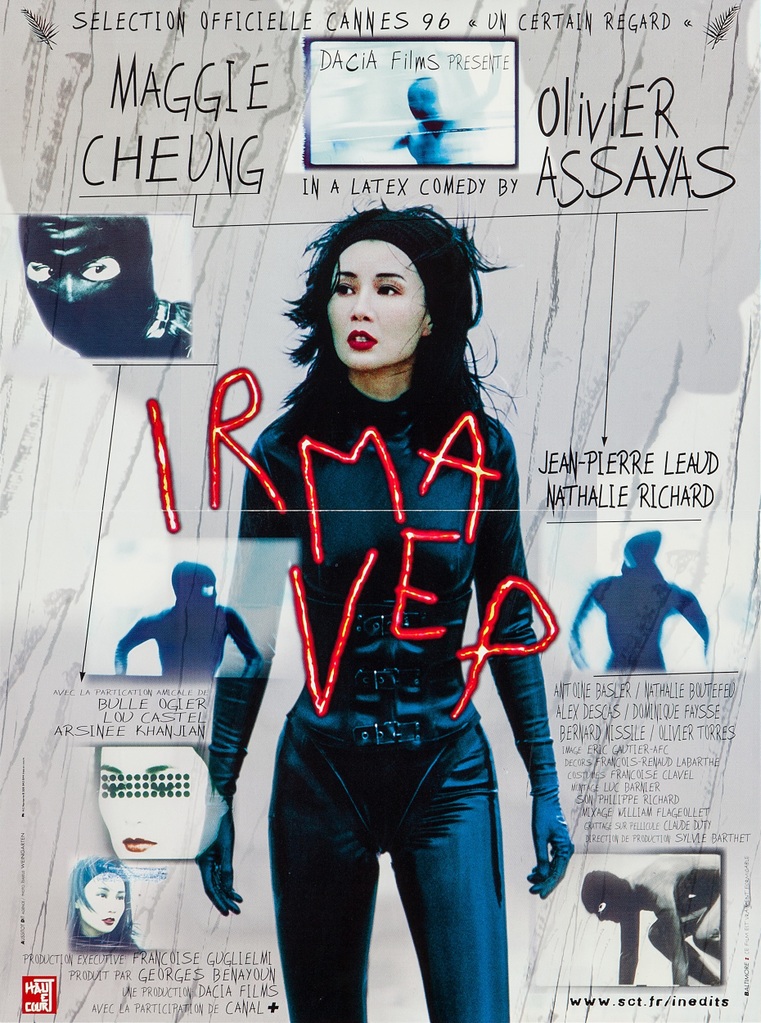

In 1996, Olivier Assayas released Irma Vep starring Hong Kong superstar Maggie Cheung as … Maggie Cheung, a superstar of Hong Kong cinema, who landed in Paris in the middle of a remake of the cult series Les vampires (1915, Louis Feuillade). In the film within the film (a fictional remake of the actual masterpiece), Maggie Cheung, the character, reincarnates one of the first femmes fatales in the history of cinema, who later became a feminist icon (Irma Vep), but it’s also a constant reflection of the actress cast by Louis Feuillade (at the time) 90 years ago: Musidora. In Assayas’ film, Maggie Cheung is also a muse for a former great director, now dealing with a creative crisis, but determined to stage his fetish (not just cinematically speaking) of dressing his lead actress in a latex catsuit. Lastly, in order to better understand the play of mirrors in the series just released on HBO Max, it should be mentioned that this mise en abyme which is Irma Vep (1996) continued outside the frame – Assayas and Cheung got married in 1998, they divorced in 2001 and collaborated one more time in 2004 (Clean).

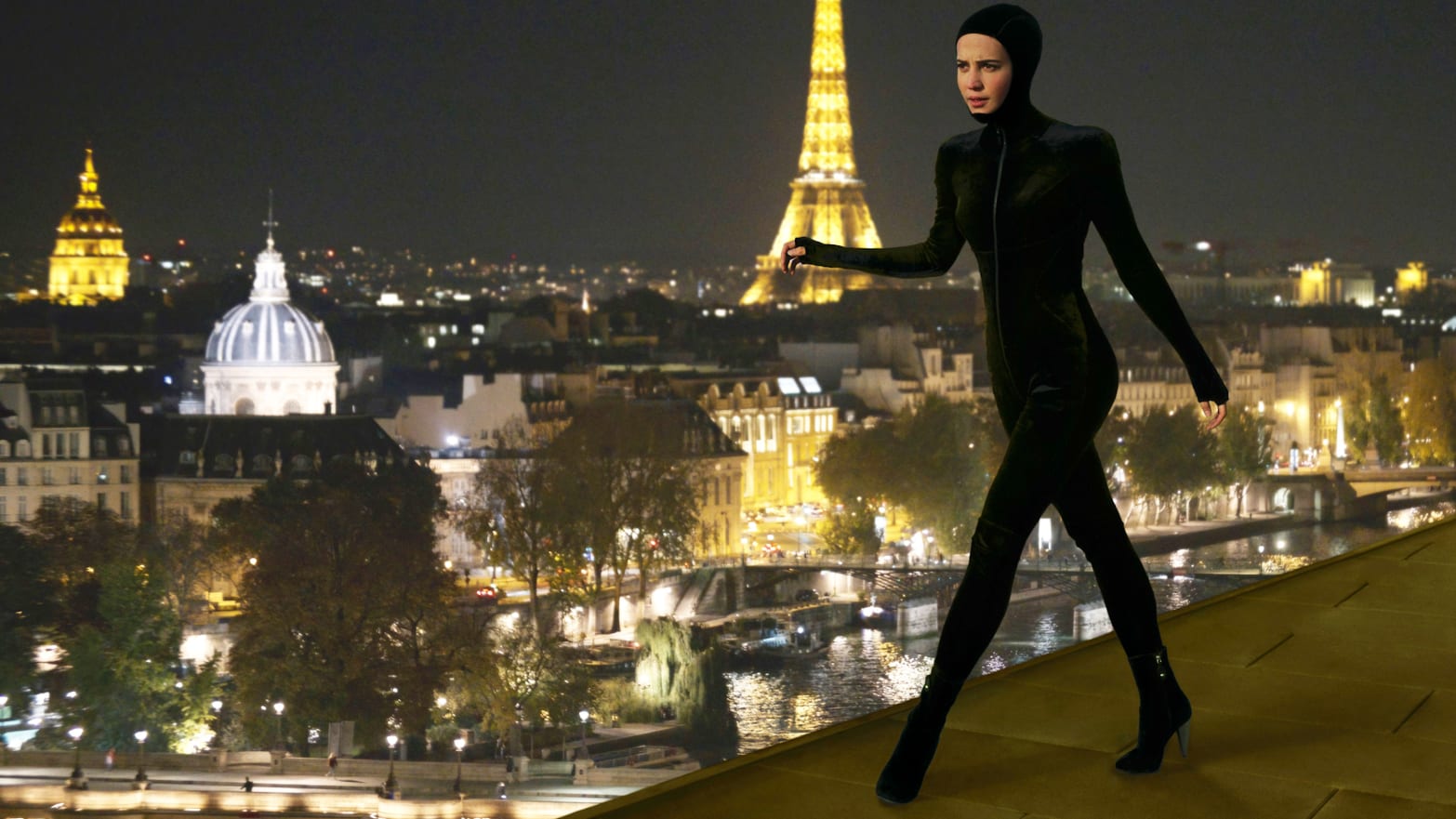

Now, Irma Vep (2022) comes with a new frame over everything I described above, fiction and reality alike. An American superstar (Mira – Alicia Vikander) lands in Paris in the middle of a remake of Les Vampires. The director is, by name at least, the same René Vidal from 1996 (played then by Jean-Pierre Léaud, and now by Vincent Macaigne). Plot twist: René Vidal has already made a remake of Les Vampires, but he feels that he still has things to say and now has carte blanche to make a new remake in a series format, closer to Feuillade’s original.

Meta plot twist: the archive footage from this first remake made by the fictional director René Vidal is actually footage from the film made by the real director Olivier Assayas. Moreover, René Vidal was also married to his main actress of Asian origin, who eventually retired from acting, as happened with Assayas and Maggie Cheung. However, Vidal’s actress/ex-wife is not played by Assayas’ actress/ex-wife. But Maggie/Irma Vep in her latex suit lives in Vidal’s fantasies, memories and dreams; probably, in Assayas’ own mind too (hard to say in this infinite play of mirrors how much is confession, how much is self-irony and how much is play for the sake of playing). The way these 1996 images burst onto the screen – a totally different texture, which practically “tears up the film” in an almost physical sense, each appearance accompanied by a piece of distinct music – is the closest cinematic representation of one’s stream of consciousness. As if Assayas were “writing” his film in real-time, disturbed from time to time by his own memories.

“This is a ghost story, movies live from the past, they live through you,” says Olivier Assayas in an HBO interview held on the movie set. This kind of promo material ironically pours into the very critical substance with which Assayas plays in the latest Irma Vep iteration. In 1996, Assayas aimed at the impasse, self-sufficiency and provincialism (disguised as egomania) in which French cinema seemed to bathe: the solution found by the director deserted by inspiration was to combine an old masterpiece of silent cinema with an Asian diva who could draw a crowd. In 2022, Assayas combines a more recent cult masterpiece (his own 1996 film) with a Hollywood superstar, Alicia Vikander, following the recent trends in the industry that have made TV series popular again (Feuillade is considered a pioneer of serial-cinema with his three masterpieces: Les Vampires, Fantômas and Judex). Of course, Assayas – not exactly an outsider in 1996, but certainly a part of the system in 2022 – is well-aware and self-ironic. The present satire is not as biting or as localized (globalization and serialization have swallowed the elitist French cinema), but the commentary is just as solid, along with the potential for comedy that can arise from the creative chaos that is the shooting of a film. It’s one of the major questions Assayas seems to ask in the shadow of the narrative: how are films (even) getting made given all these never-ending creative struggles, opposite goals, personal vendettas and on-set romances?

Beneath all this apparent chaos, Assayas actually runs a very rigorous schedule of entrances and exits, gradually revealing the machinery backstage as all sorts of characters step into the frame to carve (not necessarily with this intention) their names on this collective creative effort which is the film: I was here too! Mira (Alicia Vikander), the superhero movie global superstar, is ready to throw away the tight latex costume for something more empowering, i.e. the tight velvet costume of Irma Vep, and a pretentious director. Director René (Vincent Macaigne) shifts neurotically between impostor syndrome and megalomania. Mira with her professional, financial and romantic entourage – everybody wants a piece of everything – is the dramaturgical engine. René – modeled after Assayas’ gentle mannerisms and soft voice, and played by Macaigne with an inexhaustible flair for self-combustion – is the comedy engine (beyond the autobiographical dimension already discussed above). Between these two poles, Assayas organizes his characters/professions, checking off every possible part in this collective “miracle”: from drug dealers and extras who want to be paid as dancers (because they are shooting in a nightclub) to the psychologist appointed by the producer to certify the unstable director, kept under control with antidepressants, as “insurable”.

Each character in this panoply comes with their own micro-narrative, but Assayas makes sure to round them off with a syndrome or two of the present or all-time cinema: from #MeToo to intimacy coordinators, to the eternal dispute between TV series (industry) and films (art) anecdotally dissected by a famous German actor: “I grew up on re-runs of Dallas. I heard Rainer Werner Fassbinder was a fan, too. Used to jerk off to Sue Ellen.” Not all references are spot-on, but sometimes they land with stand-up perfection, from opening to the punchline; my favorite remains the discontent of the same German actor, who trolls (or not) some journalists by complaining about “the liberal media elite and all those Latinos stealing our jobs. It didn’t happen to me personally but look at the Academy Awards. It’s all about Mexican directors and Koreans.”

Irma Vep is – among many other things – a discussion (per se) about cinema in the broadest sense, but one shouldn’t dig too much into the dialogues orchestrated by Assayas and into the references that flood the cinephile conversations (in fact, all conversations are cinephile) to seek what the author meant. The characters are lively, autonomous, contradictory and histrionic, not some authorial mouthpieces. And even if you’ve never set foot on a set, you don’t need to do that to understand and revel in the creative dramedy.

Irma Vep is available on HBO Max.

Stranger Things 4 (Matt and Ross Duffer, 2022)

Stranger Things 4, a (pop)cultural phenomenon in itself, has produced a smaller cultural phenomenon, which appears to have no end. Kate Bush’s 1986 song Running Up That Hill reached number 1 on the charts after being used intensively this new season (the action takes place in 1986). Now that we’ve found out how everyone listened to Kate Bush before it was cool, let’s give credit where credit is due, especially since Netflix is releasing the last 2 episodes of the season on July 1 (divided for obscure reasons into 7 episodes of over an hour released at the end of May, and these last 2 episodes that practically make up the length of a movie).

Stranger Things is going strong after four seasons and it’s not Kate Bush’s doing (although season 5 will probably feature the British singer in heavy rotation). The Duffer Brothers – directors, screenwriters and twins – set off with a very simple artistic vision, that of curating the American pop culture of the ’80s, which they executed perfectly: from board games, music and movies to objects and rituals impregnated with localized nostalgia (nostalgia that is often filtered by the very representation of these objects in the audio-visual production of the era). In a way, Stranger Things reaches the highest level of sophistication as regards remix culture. The simple idea from the beginning is still working pretty well, and it’s just as rewarding, despite the fact that Stranger Things 4 is more of the same old things.

The premise is the same as always: even stranger things than before are happening in the small town of Hawkins, Indiana. The plot leads to a secret lab, the kind of fringe activities conducted by the military-industrial complex that Hollywood enjoys so much (somewhere, there is a research paper waiting to be written about the impact of these evil government-type narratives on the public’s defense of the right to carry firearms). Their test subjects are children with psychokinetic abilities, and the strongest of them (Eleven) causes a rip in the space-time continuum, granting access into Hawkins to all kinds of monsters from a parallel universe (The Upside Down). Eleven escapes, is adopted by a widowed sheriff, who is haunted by his own trauma, and joins a group of boys whose parents obviously have no idea that their children save humanity every now and then (it’s the ’80s, so there is a much more relaxed parenting style).

The above observation is meant as a recap of the first season, but all that follows is like revisiting the same themes, traumas, and in general the same dramatic structure. Especially this new season, which throughout its 7 episodes is trying to tempt us with endless flashbacks on the origin of evil we already knew about. Only that now the starting point is a bit modified to throw Eleven into new psycho-affective disarray (the syndrome of the orphan with superpowers wondering whether she is a superheroine or a monster) and to introduce a new villain.

As in previous seasons, the antagonist sent from the underworld is borrowed from other sources with a patented gimmick. At the beginning of each season, the nerd gang gathers in a basement to play Dungeons & Dragons, and the big monster (Vecna) they fight on the game board will lend its name to the real monster. The fourth season’s new twist – which the creators must have been very excited about, otherwise they wouldn’t have wasted 7 convoluted episodes with that – is to imagine another villain from the Upside Down and to divide the protagonists into separate groups, each chasing one of the monsters. Much in the vein of Scooby-Doo, which the series seems to have always emulated – let’s turn off the flashlights and explore this haunted house going opposite directions – the groups split into smaller groups, searching for each other, gathering clues along the way. The moment of revelation/unmasking is indeed well written and a breakthrough that points out very well the mid-season climax, but considering how much the entire plot is dragged on, you can’t help but wonder if it was really worth the wait. And I didn’t even mention the ridiculous Soviet escapade of some of the protagonists, which seems to have no relevance to the story except to take a character out of Siberia, who had been kidnapped by the KGB in season 3. The creators got it right in terms of exploring the feuds of the Iron Curtain (it couldn’t be more emblematic for the ’80s era), but the whole account inevitably turns into too many things.

Ultimately, Stranger Things somehow disappoints, And that is because it shows too much ambition, which translates into a huge budget ($ 30 million per episode!) for basically using the same limited artistic resources. As for the horror part in its many forms, pastiches and tributes, that one continues to be perfectly balanced (atmosphere, violence and humor), and the eighties nostalgia is superbly stylistically infiltrated, aside from the specific rewards based on vanity (i.e. the Kate Bush syndrome). These things have always been there, but they never made up for the script or portrayal of the characters … because the ambitions were not at this level.

In season 4, the kids have grown up, they are now in high school, and kind of lost touch with one another – for different reasons, which are partly related to the typical adolescent universe that we have encountered so many times in classic American coming-of-age movies: nerds vs. popular, long-distance relationships put to the test, bullying and sexual awakenings. And when it comes to this transition from childhood to adolescence, none of the characters seem to look the part. It doesn’t help that three years have passed since last season either. After a perfect storm – the COVID-19 pandemic (causing several delays in production), a well-earned success (the series launched several careers, hence new delays) and partially failed creative ambitions (expanding the action to multiple locations) – the teenagers starring as children in the first seasons now look much older than their characters. In view of this situation, the creators decided to hide the actors behind some stupid (vaguely eighties) hairstyles and general awkwardness. The bigger problem is that, losing the attributes and charisma they had before as children – for this kind of series, the matter of acting is almost always solved by casting –, not all of them have learned to act in the meantime. But even those who do know how to act are forced into a role that they’ve visibly grown out of.

Before being taken by Netflix, Stranger Things received rejection after rejection from TV networks on the grounds that no one would watch a series that addresses such issues and with children in the lead roles. The suggestions they got were either to make a children’s series, but less scary, or to keep the tone, but with adult protagonists. The Duffer Brothers stuck to their original idea and hit the jackpot at an unexpected level. Sure, in a few months Netflix will announce a new viewership record for another production, but does anyone even remember the previous records? Did anyone stop to search for the Bridgerton soundtrack, for example? It’s maybe harder to see through all that glitter and thunder surrounding the launch of the series, but Stranger Things made it on the same pedestal as the eighties models that inspired it: cultural anchors recognizable even by those who haven’t seen any of the episodes. After all, Stranger Things 4 is in itself a nostalgic experience: what keeps you watching even when it goes south is the memory of previous seasons and the attachment to the characters you know from six years ago.

Stranger Things is available on Netflix.

Film critic and journalist, UNATC graduate. Andrei Sendrea wrote for LiterNet, Gândul, FILM and Film Menu, and worked as an editor on the "Ca-n Filme" TV Show. In his free time, he works on his collection of movie stills, which he organizes into idiosyncratic categories. At Films in Frame, he writes the Watercooler Wednesdays column - the monthly top of TV shows/series.