Watercooler Wednesdays: The Kingdom & The Crown

Watercooler Shows, the trending series that everyone talks about the next day at the office, around the water cooler. Watercooler Wednesdays seeks to be a (critical) guide through the VoD maze: from masterpiece series to guilty pleasures, and from blockbusters that keep you on the edge of your couch to hidden gems; if it leads to binging, then it’s exactly what we’re looking for.

The shows we focus on this month don’t have much in common, but they do align semantically: The Crown and The Kingdom.

But first, a special mention for a title from the same extended semantic field: El Presidente: Corruption Game – about the king sport in the era of João Havelange, who turned FIFA into the (corrupt) money-making machine it is today. It’s a recommendation that didn’t make it into the November feature but can’t be ignored in the context of the World Cup Qatar 2022, whose underneaths would probably embarrass even Havelange.

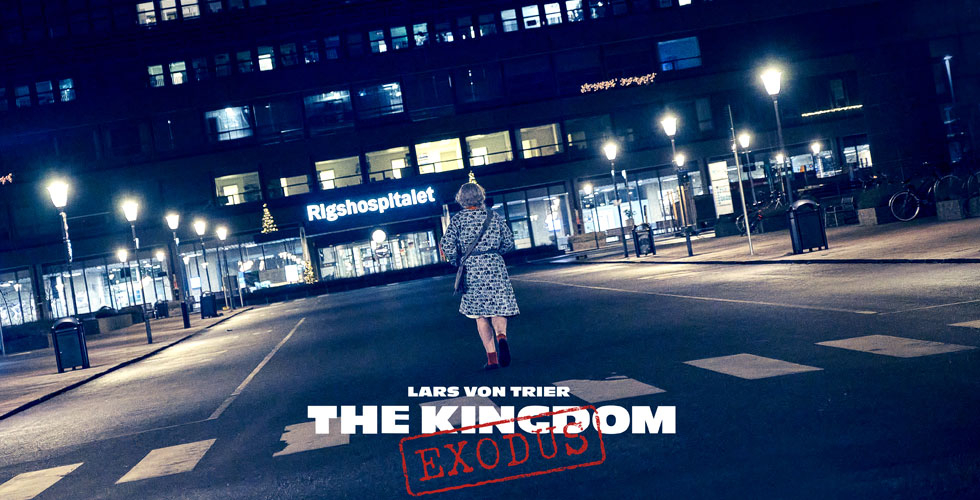

The Kingdom: Exodus (Lars von Trier, 2022)

It is happening again … again.

The line is, of course, from Twin Peaks, the revelation and inspiration that pushed Lars von Trier to make his own cult series. David Lynch ended Season 2 in 1992 with a diegetic promise that the protagonist would resurface after 25 years. Willing or not, Lynch kept his promise (what had been intended as a cliffhanger turned out to be the longest ellipsis in the history of cinema), and now we have Lars von Trier also returning with a new season after 25 years.

If Twin Peaks made history (also) with the melange between horror, soap opera and comedy, The Kingdom is a combination of horror, medical drama and workplace comedy – shot, of course, by the rules of Dogma 95. The Kingdom – originally titled Riget, short for Rigshospitalet – it’s a real hospital in Copenhagen and a gateway between worlds in Lars von Trier’s vision. Built on the site of the “bleaching ponds”, the brutalist 16-story monstrosity hides all sorts of monsters, from supernatural beings to the white coats roaming the halls.

Season 3 opens with a splendid mise en abyme: in a suburban cottage, a wrinkled eye stares at the TV screen. Violent images follow one another in a fast-paced sequence: an ambulance, screaming, then an explosion… a figure lingers on the retina and starts to sing a lullaby with eerie echoes. Countershot: a young Lars von Trier stuck on the TV screen sardonically ends the last episode of Riget II, which aired in 1997 – in the vein of old-times horror hosts, the director attends all his episodes. Like Assayas in Irma Vep (which we recently discussed here), Lars von Trier fuses reality with fiction as in a Möbius loop: a character from the third season watches the previous season on TV.

“That’s not an ending,” blurts out annoyed the retired cinephile as she scribbles the names of the characters on a piece of paper – then puts on her pajamas, ties herself to the bed and awaits the message from beyond. Karen is a possessed sleepwalker, a mysterious voice calls upon her in need of her assistance: the carnage that ended season 2 left things unfinished, there’s still a lot of suffering in the bowels of the hospital, and she can set it free. In this character’s reality, the world depicted in The Kingdom and its previous events exist at the same time in the same universe. Karen checks into the hospital to complete her mission and seeks allies among new and old characters – everyone agrees that Lars von Trier is an idiot who ruined Riget‘s reputation with his series.

While Karen is the patient catalyst for the supernatural narrative, neurosurgeon Halmer is the magnetic point that guides the hospital employees into a narrative arc, forcing them to ally against him in a series of absurd pranks. Halmer is a recent Swedish import, and his contempt for the Danish way of doing things is obvious. Humiliated by his Danish colleagues, Halmer finds refuge in Swedish Anonymous – vexed expats like himself, doctors and nurses who walk around with their Volvo hubcaps in fear of Danish crime. Pushed to the limit by the cultural conflict, Halmer is the perfect opportunity for evil to be unleashed once again (before getting to the horror part, Lars von Trier proves to be an excellent comedy director).

The Kingdom: Exodus is the third season of the miniseries trilogy started by Lars von Trier in 1994 and continued in 1997 (each of the two featuring four episodes). “Season” and “trilogy” aren’t quite the right terms here: a third season was already in the works back then – the script has certainly been altered a great deal in the meantime – and probably wasn’t supposed to be the last, so it wasn’t intended as a trilogy. In August, the director confirmed he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s, and that puts a very different spin on how DR (the Danish broadcasting company) broke the news two years ago that it had begun production on a third and final season of The Kingdom.

Why are all these details relevant? Because each episode practically ends with an afterword by the author. In previous seasons, an impertinent Lars von Trier (his very words) would pop in to comment on the events of the episode while the credits rolled. The same now, only he does it as a voice-over, acknowledging the ravages of time: “I have physically withdrawn and am no longer really in the picture”. Exodus. It’s a bitter confession that he orchestrates, as he always does, starting from text to mise-en-scene and camera movement; cinema remains the commander in chief: the camera spots his polished shoes under the red curtain behind which he hides, and his autobiographical speech pours into the analysis of his own work and it’s author, inviting us as always “to take the good with the evil“.

The melancholy in this image of the artist framing his own film from within inevitably permeates the already porous content of The Kingdom. Blending old and new characters, the reality of this 25-year ellipsis is reflected in the wrinkles of Lars von Trier’s regular collaborators and the absence of those who didn’t make it to Season 3 (after all, a normal topic for a series about a hospital). And the red curtain is not random either, which is why I began the review with a reference to Twin Peaks. David Lynch’s Return, like Lars von Trier’s Exodus (the difference is that Lynch stars as a character, not as a raisonneur), is a film about getting old and death constantly traversed by the same melancholy: the artistic object itself, which should suspend time so as to relive it with every “screening”, is also a testimony to its irreversibility.

The Kingdom is available on Mubi.

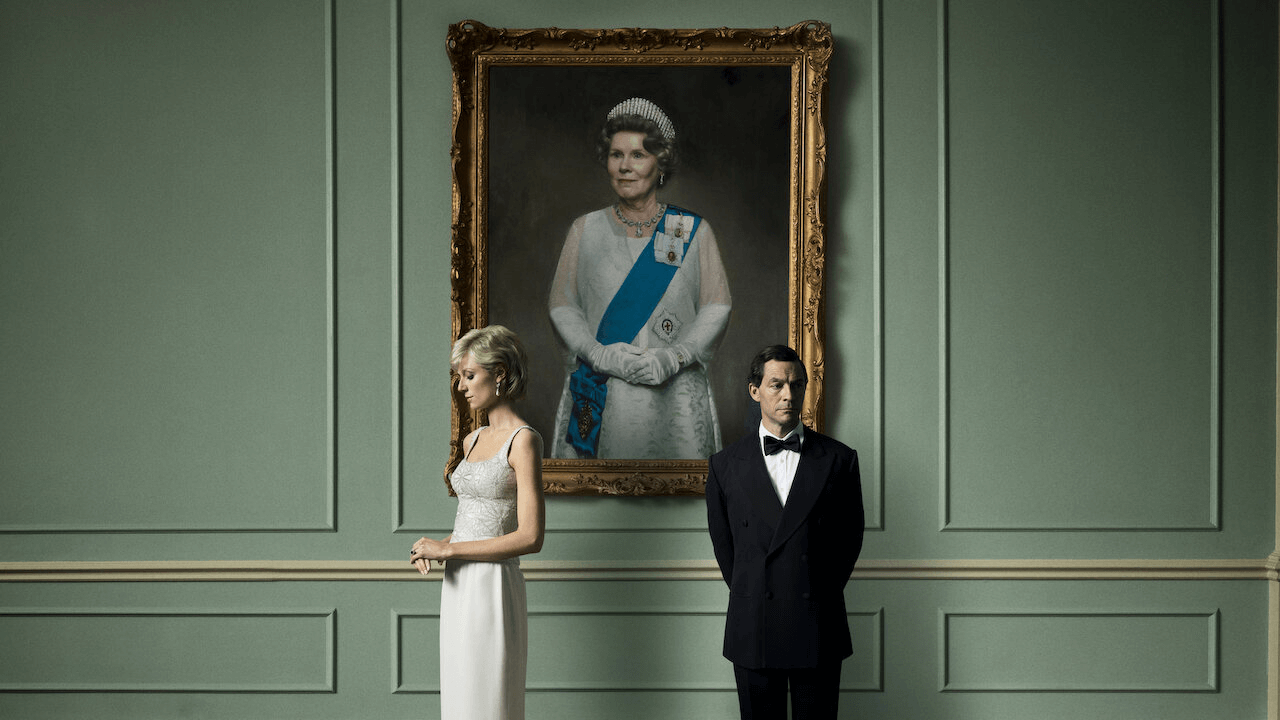

The Crown (Peter Morgan, 2022)

At almost every turn, The Crown gave me that weird “I’ve seen this before” feeling. It took me a while to realize that that deja-vu was actually the reality of the British monarchy under Elizabeth II. A sometimes lived reality (“Nine in 10 living humans were born after Elizabeth became queen,” has been a popular headline this year), but mostly mediated by all kinds of cultural products, from history books to tabloids and, of course, countless other productions inspired by the same “true events”. It seems like an absurd criticism to bring to a biography TV show that claims to be a “fictional dramatization” that was “inspired by real events” … but in the end, The Crown – a depiction of the second Elizabethan era – whether it rigorously sticks to the facts, or takes some apparently scandalous liberties, is rather a marginal autobiography of the contemporary viewer. We are not really watching something, we are watching our own perception of that something. The Crown fails miserably not because it’s not historically accurate, but because it presents itself as a digital video magazine – it entirely fails to raise some three-dimensional characters from the psychological flatness of a newspaper page.

Season 5 roughly overlaps with John Major’s tenure as prime minister, the handover of Hong Kong, the Queen’s state visit to Russia, and a few other minor events for the Commonwealth. The focus is, as always, on the disruption of the royal family by countless scandals and divorces, the most famous of which is certainly the one between Diana and Charles, the peak of that annus horribilis (1992), as the Queen herself called it in a speech. The notorious Diana-Charles-Camilla triangle is, in fact, the only vaguely interesting thing in the entire season in terms of dramaturgy.

Isolated from all the expository baggage that surrounds them, the three already iconic characters (played by Elizabeth Debicki, Dominic West and Olivia Williams) manage here and there to get a bit of psychological depth and dramatic tension. Criticized for the way it portrays the members of the royal family, season 5 strangely feels like an homage to Charles (III as of late). Of course, the new king is well past the age when his mother was accused of Queen Victoria syndrome, but Charles back then (who admits that the show gets his character and ambitions quite right) saw himself as a reformer of the monarchy, which needed to be adapted to modern times, a progressive. Charles and Camilla are surprisingly the characters you grow most attached to; their phone conversation – a reenactment of the famous Tampongate, where he jokes about what it would be like to reincarnate as a tampon to be closer to her – is, without being ironic, the artistic peak of this season.

Apart from this love triangle, The Crown has very little to offer in terms of dramaturgy: text, drama and characters; you’ll never find all three at once, maybe two every now and then. The Crown is largely a dialogue- and text-based series, somewhat in tune with the institution it represents: the royals have very limited powers, but are free to speak. Most of the time when they do, it feels like someone pressed play on a Wikipedia page. In a classic grandma-versus-technology scene (more precisely versus a TV remote control; the premise itself is stupid, let’s move on), the Queen and grandson William are interrupted by the Queen Mother. The Queen Mother, as happens with many characters here, is not a human but a transmitter: “It’s so sad to see her struggle to understand a medium with which she is inextricably linked,” she sighs anthropologically as if she has just read her obituary on TV, and then begins a history lesson about the first BBC broadcast.

On the other hand, nothing important really happens in The Crown (in this season at least), it is a family chronicle that combines rumors (what’s been written in the press) with the mundane (assumptions based on our own experience of family life). The main problem – which also has to do with the characters, we’ll get to that – is that the sum of these two things is simply boring. In the second episode, we are tortured for minutes on end with Prince Philip’s passion for carriage driving: we see him hunched over his desk, leafing through various treatises and papers, drawing up sketches, then personally overseeing the restoration of a turn-of-the-century carriage under the admiring gaze of his craftsmen, all set to music. Who cares? He’s an old man fixing his wagon. The secondary problem arises when the show tries to merge these two realms (rumors and mundane) through a dramatic bridge, inventing ridiculous conflicts that lead nowhere: the carriage is for a female friend/relative, a rumor of a rumor, a pretext to fill another episode.

The biggest shortcoming, however, is the characters. The royal family (depicted in The Crown, to be clear) made me think fondly of the French Revolution – it’s impossible to empathize with most of them … maybe just with the army of corgis. Perhaps the most irritating thing is how the show wastes its actors, letting them get lost in verbal and sartorial tics and impersonations. In the end, all that remains of the great talent assembled by The Crown are Charles’s ears, Diana’s brow arches, Camilla’s bangs, John Major’s uptightness, Boris Yeltsin’s lack of manners fueled by alcohol … which is exactly what we all “knew” already, i.e. their portrait in the collective imaginary.

Over all reigns a queen disconnected from the problems of her “subjects”, a category that includes, of course, her own family. It’s not hard to understand the concept behind Imelda Staunton’s performance: an impenetrable authority figure, rarely shedding a tear, never raising her voice; it’s the persona she built, the sacrifice for a country that went its own way, for some children who only cause problems. It’s the image cultivated by the late Queen herself, perhaps the artist’s intent to stay true to what is visible and known should be appreciated. But that doesn’t mean that the imitation of that product is something worthy of attention.

The Crown is available on Netflix.

Film critic and journalist, UNATC graduate. Andrei Sendrea wrote for LiterNet, Gândul, FILM and Film Menu, and worked as an editor on the "Ca-n Filme" TV Show. In his free time, he works on his collection of movie stills, which he organizes into idiosyncratic categories. At Films in Frame, he writes the Watercooler Wednesdays column - the monthly top of TV shows/series.