Festival Diary: Berlinale 2023

Returning for the third time to the festival whose heart is beating in Potsdamer Platz, Flavia Dima keeps a diary of this year’s Berlinale – with fresh insights into films, events, and discussions.

***

14 February: Preamble in Bucharest

Today we’re heading out to Berlin on the evening Ryan Air flight – it’s my third time at the Berlinale, after the 2018 and 2020 editions. The festival doesn’t feel as scary and overwhelming as it did in my first years: slowly but surely, I’ve learned how to navigate the paths of this festival with an enormous selection and to tame my sense of FOMO. So I set off with the peace of mind that I probably won’t catch everything I wanted to see, and that I have to be realistic about my expectations; the 2020 Berlinale was one of the last moments of normalcy in my life before the pandemic broke out, so this return to Berlin is also sort of symbolic ending to a very troubled and strange period.

It’s the 73rd edition of the festival, the first edition without any sort of restrictions – which forced the festival to go online in 2021 and affected the course of last year’s in-person edition – thus marking a return to a normal state of affairs. And it’s returning in big fashion: with none other than Kirsten Stewart as the jury president (where, amongst others, she’ll be joined by Radu Jude), a new partnership with Armani Beauty, as well as – most importantly for local audiences – a substantial Romanian presence at the festival.

I already know that I have two absolute must-sees at the festival: Angela Schanelec’s Music and Hong Sang-Soo’s In Water – two of my favorite contemporary filmmakers, known for questioning classic narrative structures in cinema; I also really want to catch the Romanian films, as well as new works by Christian Petzold, Lois Patino, Melissa Liebthal and Margarethe Von Trotta (which regards the poet Ingeborg Bachmann, played by none other than Vicky Krieps!). Of course, my list of titles is much longer, but these would be a few musts; I hope to also have time to squeeze in something from the retrospective of coming-of-age films and the one dedicated to filmmakers of color that worked in Germany, organized by the Forum.

I am going to the festival with Pedro, my partner (in crime), who was also with me three years ago and is the perfect person to share these days with.

***

15th of February, day 0: Warm-up

We took it easy in the morning and spent some time with our hosts, Christi and Alex, who welcomed us with open arms to their apartment in Ostkreuz – and then we took a walk around the neighborhood (with a mandatory stop at Mustafa’s Kebap, one of the city’s legends), and then went to Postdamer Platz to pick up our badges. Instead of the ubiquitous festival tote bags, we got a red fanny waist bag – chic, tres Berlin –, and while I hear that some journalists are unhappy that they can’t use them to carry their laptops (no shit, Sherlock), I’m more than happy with it.

In the evening, we went to the opening of the parallel Woche der Kritik – an event in the vein of the Semaine de la Critique, organised by the German Critics’ Association, with a unique selection of films, and where my partner Pedro worked as programme coordinator. The event took place at the Akademie der Kunste in Pariser Platz. A building with huge glass windows, through which we could see the Brandenburg Gate, in front of which several thousand people have gathered to commemorate the victims of the earthquakes in Turkey. During the evening, the singing of an imam sometimes rings through in the hall, rendering things pointless: after all, whatever we might have to say about cinema pales in the face of such tragedy.

The event (under the title “Cinema of Care”) is relatively lackluster, however – starting with a speech by the organisers, presented in both German and English, which eats away three quarters of an hour (notably, the organisers discussed at large about the precarious conditions they faced in organising this edition). A keynote speech by Professor Isabella Lorey – in which she examines the gendered and apoliticised nature of care work, its devaluation under the capitalist and patriarchal system, and the forms of violence (economic, “domestic”, legal and macho) that affect it – raised the level of the discussion, but things quickly deflate afterwards.

A screening of a (quite good) short film by Elke Marhöfer was followed by a discussion via Zoom that quickly turned repetitive, so that it’s already been more than two hours when the main attraction of the evening began – a panel with Claire Denis (!!), Marek Hovorka (director of Ji.hlava) and curator Abby Sun, moderated by Film Comment’s Devika Girish.

Denis was in great shape, doling out poetic thoughts – she treats the words “which” and “aesthetic” with circumspection; at one point she said that watching a film alone at home is like „a kind of masturbation” – which made us laugh in a oh, what pandemic has done to us way. Overall, the discussion failed to reach a common denominator. It seemed like everyone’s speaking by themselves (with the exception of Hovorka, at times, who tried to build bridges with what the other two speakers were saying).

By the end of the discussion, it’s already been three hours with no breaks (!), so the ending was rather abrupt, leaving no space for questions from the audience, thus leaving us with a sense of confusion rather than one of enlightenment.

***

16th of February, Day 1

An expanded cinema exhibit, a tough reenactment and a film like a nostalgic piece of candy

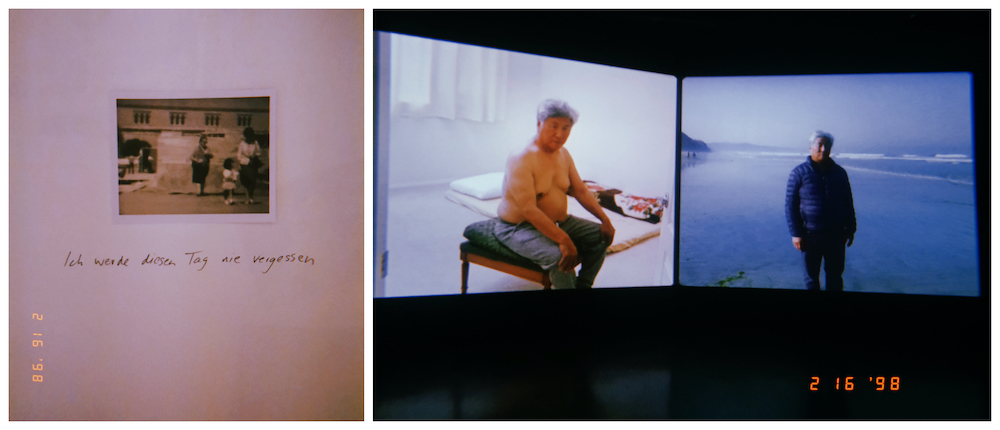

We start our first official day of the festival with a visit to the Wedding district, to silent green, where the Berlinale Forum Expanded exhibition – titled An Atypical Orbit – is taking place. An annual fixture of the Forum since the Berlinale’s 56th edition, these audio-visual exhibitions are inspired by the concept of expanded cinema – that is, a cinema that seeks to evolve in a different context other than the theater. (Incidentally, the exhibition also features the work “Time Tunnel: Takahiko Iimura at Kino Arsenal,” which reworks an installation shown at the Arsenal in 1973, in the early days of the Forum.)

The exhibition features a mix of works by young rising stars on the festival orbit, such as Eduardo Williams, who is showcasing with his Un gif larguisimo – a combination of images from an endoscopy with holiday footage shot on a telephoto lens – and towering figures. Just after entering the Betonhalle, one can see Michael Snow’s Puccini Conservato playing on a classical TV screen, a tribute to the great Canadian experimental filmmaker that passed away this January.

One of the exhibition’s central themes is family – and its most prominent artist, Tenzin Phuntsog, is featured with three works exploring the concept of migration. One of them, which opens the exhibition, depicts the artist’s parents (who migrated from Tibet to the US) as they are asleep, on a modest mattress, just like the one they had used after arriving. The most moving of the three works is composed of three jewel cases that contain three small screens, playing home videos from Tibet in a loop. Last but not least, another notable work from the exhibition is an interactive installation exploring the idea of false family memories, belonging to Tamer al Said – who used images found in a Greek archive – and which invites visitors to use printed snapshots from the films to write down memories (whether true or not) in a few notebooks.

Then we head off for the first film of this edition, at Kino Arsenal: Mehran Tamadon’s Where God is Not, in which the director invites three former political prisoners from Iran’s to describe the conditions in which they were held and the forms of torture that they were subjected to. A film with an interesting, albeit not unheard of apparatus – using minimal re-enactments of the prison’s inner settings and the words of the former prisoners, the viewer is left to imagine the incredible cruelty of these prisons (with everything from intense psychological torture to ferociously cruel beatings).

Constantly present in the frame, Tamadon not only demystifies his presence within this process, but also opens himself up to criticism (for example, in the moments when his witnesses are overwhelmed by the direction in which he is leading them), as well as to a meta-cinematicbgaze. A very tough film, for sure, and with rather nihilistic conclusions. Ultimately, the film operates in a way that is very self-conscious about the fact that it is a necessary document, but one scene in particular questions whether it could have any effect on the torturers and sycophants of the regime – in the words of one of the former detainees: “So, what do you think will happen if you go back to Iran? That they will put you in prison and then all the directors and actors in Europe will sign open letters for you? Nice!”

Our evening concludes with an almost “opposite” film, Matt Johnson’s Blackberry, which is sure to make its way to Romanian screens. Briefly put, the film is a chronicle of the team that created the legendary smartphone that dominated the market in the 2000s. But don’t expect a film like The Social Network, nor one like The Big Short. Johnson creates a comedy in the vein of shows like The Office, heavily reliant on language and character humor, in which he clashes together the tech sharks of the early august with the nerdiness of engineers who spend most of their time playing Doom II and Starcraft and binge-watching movies like Star Wars, Raiders of the Lost Ark and They Live.

Blackberry is a delicious response to all the recent biopics that take themselves much too seriously, and is as light-hearted and funny as it is deeply critical of tech corporatism. Plus, it’s also a nostalgic piece of candy for the millennial audience, that it will inevitably lure into a game of “spot the digital artifact”: with everything from Age of Empires to Winamp.

***

16th of February: queer literature, a Taiwanese meal, and a cultural artifact

We start our morning with Orlando, ma biographie politique at Cinemaxx – the first film by renowned theorist Paul B. Preciado, known for his writings on queerness, sexuality, and identity. The film enters a dialogue with Virginia Woofle’s classic novel in what is a loose adaptation steeped in the concept of fluidity: in what regards both gender and formality (a mix between fiction, documentary, and an essayistic format).

Working with a novel considered to be a seminal work of modern world literature, ahead of its time in terms of gender representation (the titular Orlando transforms from male to female in the middle of the novel), but also with references to another film adaptation (Orlando, r. Sally Potter, 1992). itself considered a classic of New Queer Cinema, Preciado aims not so much to modernize the novel by expanding its representation of the trans / gender non-binary experience, as it seeks a hidden Orlando within each trans person. (Incidentally, every performer in the film is introduced with the same formula: “Hi, I’m X, and in this film, I’ll be playing Orlando, by Virginia Woolfe.”)

Preciado’s relationship with Woolfe is largely admirative, as he finds complex political connotations within her work (both in terms of sexuality, but also colonialism, nobility privilege, and legal identity), but it’s also rather critical. The first half-hour of the film is devoted to additions and corrections: for example, about the medicalization and pathologization of trans people, which remained unaddressed in the original novel. After this first half hour, which is largely a collection of relatively loosely-knit vignettes, the free adaptation begins proper, as Preciado employs trans people of all genders, ethnicities, and ages to reenact the novel’s most iconic moments, interweaving them with the actors’ biographies as well as his own thoughts and memoirs, like cinematic footnotes. Overall, the film is a manifesto that buzzes with verve, political nerve, and boldness. And even if this 2023 iteration of Orlando is not a perfect film, one must keep in mind that some of the very concepts that the film interrogates and deconstructs are those of perfection and imperfection.

Then comes lunchtime – and it’s a joy that our next film of the day is around Zoo Palast, at the Delphi (the Berlinale’s most beautiful cinema, by far), so we use the occasion to take a trip to Lon Men’s Noodles to, the delicious little Taiwanese restaurant where we had one of the last dinners in town before the 2020 lockdown. I order the same peanut-sauce noodles I got last time, which I then tried to reprise at home countless times over the past three years; as nice as it is to close all those circles, it also makes me ponder about how many things have changed in the past three years.

We stop for coffee with our MUBI friend Danny and see Kara Kafa (Black Head), the first film in the diasporic film retrospective presented in the Forum, a film that was banned in Turkey and led to the exile of its creator. An utterly fascinating artifact of a fringe cinematic movement, which has now been unearthed: even though it’s shot like an eighties TV series – crazy zooms, an overly melodramatic acting style at times – Korhan Yurtsever’s film is so deeply political that it’s almost agitprop.

At the center of the narrative we have the family of Cafer, a Turkish immigrant working in a local factory, who undergoes radical changes once they arrive to Germany: his partner, once a housewife, is forced to take a job as a seamstress, his children don’t manage to fit into the (pre-)school system, and the husband’s traditional authority is eroding little by little, every single day. The couple’s conflict is quite interesting: while the wife experiences a political awakening and joins a Marxist feminist cell together with her work colleagues, he takes a rather right-wing stance – that of the docile immigrant, who is not at all willing to come into conflict with the powers that be in his new country, even though said powers exploits his labor and make him dependent of said exploitation. With little notes taken from the neorealist tradition, especially from De Sica (including a scene that heavily features a bicycle), Kara Kafa is indeed dated in some respects (it takes a rather awful stance on the issue of domestic violence), but it remains a political testament that is still in many ways valid.

The evening closes once again at the Cinemaxx, with Dustin Guy Defa’s The Adults (the second North American film of this edition, already): enjoyable, but completely innocuous. Its premise and execution are quite typical of American indie flicks – it’s a homecoming movie, with heaps of quirky humor and cinematic references (everything from Buster Keaton and Godard to The Lion King and The Simpsons), and, on top of it all, it stars Michael Cera.

If the 16-year-old were the one watching this film, she would have been mind-blown and would have certainly memorized some of its lines. But since this is the 29-year-old me, I’ll take it as a respite from an otherwise deeply political selection of films at the Berlinale, a cute little diversion which leaves me with only one revelation: actress Sophia Lillis, who has all the facial and bodily expressiveness of a silent film actress, so sincere and mesmerizing that she takes over the entire screen in her role as Maggie, the family’s little sister.

***

18th of February, Day 3

Some shorts, a disappointment and a surprise

Packed day, today – which began at 9:30 at Cubix Alexanderplatz, with a screening of Between Revolutions, then a quick run to a neighborhood cafe to jot down my thoughts on the film for our review of Romanian films. In front of the cinema, the festival has put up the screen that broadcasts the festival’s press conferences, which was formerly placed at the Sony Center (a heart of the festival in 2018, now undergoing capital repairs, and with a Cine Star that has shuttered down) – an occasion to catch a glimpse of the press conference for Sean Penn’s film about Ukraine and Zelensky. (The only people I know who went to see the film were assigned to write about it by their newspapers, and that says a lot about how people regard the actor turned “documentarist”.) I can’t hear much of it because there’s a lot of traffic in the area and it’s raining cats and dogs, but I do see that Sean Penn is wearing a bowler hat that says Killer Tacos, in pink. Amazing.

Later on, I meet up with Oana Ghera and we go to the press and industry screening of the shorts – programs I & II. Of course, as with any big festival that has a programme of shorts, meaning that they’re tailored to touch upon a little bit of everything, it’s impossible to really like them all. But I’ll point out two that I really enjoyed – Anaïs-Tohé Commaret’s 8, a surrealistic exploration of suburban life in the French balieues, and Anthony Ing’s Jill, Uncredited, which reclaims the image of an actress who has had a prolific career as an extra, is a small ode both to her, and to all the actors and actresses who appear in the background of the images we see on the big screen, who often remain suspended in our peripheral vision.

While on the way to the last screening of the day, I decide to take a walk from Checkpoint Charlie to Potsdamer Platz, via Friedrichstrasse and Unter den Linden, which is my favourite part of central Berlin.

Then comes this edition’s first true disappointment – Cidade Rabat, by Susana Nobre. I’d seen the filmmaker’s previous film, which was shown at the 2021 Berlinale, No Taxi do Jack – a playful and soulful hybrid portrait of a taxi driver – so my expectations for this film about a producer going through the loss of her mother were high enough. And the film’s prologue – which briefly tells the story of an appartment block and its inhabitants, told from the perspective of someone who grew up in that building – seemed perfect: but it all goes downhill from there. Europudding, as my colleague Victor Morozov calls it: again, we stare at an often lonely, constantly frowning middle-aged woman as she’s going through the loss of a parent, who needs to dance to a stupid song halfway through the film for us to understand that “she’s in a crisis”, as she’s wandering through a collection of dry vignettes that really want to transmit something about the nature of grief but also about social privilege, emotional detachment in modernity and all the other common places of recent cinema, but without having any concrete substance or anything new to say. Rinse and repeat. What a shame.

While on the way to the last screening of the day, I decide to take a walk from Checkpoint Charlie to Potsdamer Platz, via Friedrichstrasse and Unter den Linden, which is my favourite part of central Berlin. Probably because it’s the neighborhood where the old city is best preserved, a place where you can get rid of endless skyscrapers and glass buildings – but I stumble upon what may well be a future Radu Jude film: the entrance to Humboldt University is blocked by dozens of extras dressed as SS officers, some riding vintage cars stuffed with books (they’re probably filming a book burning scene?), all young men, all wearing swastika armbands. And I must admit that this is not really a sight I would have loved to see, especially not – of all places in the world – in Berlin.

Finally, the last film of the day – which turns out to be my fifth screening of the day, a record that I hadn’t equalled in quite a long time! – and it’s the best one of my entire Berlinale so far: Bas Devos’ Here, which was shown in the Encounters section. Using long, static shots filmed on heavily saturated stock in academic format, Here follows a few days in the life of an immigrant construction worker, Ștefan (Ștefan Gota, in a very delicate performance), who is about to return to Romania for his summer vacation, and who goes to meet up with a few of his close ones, who are immigrants themselves, before his departure.

In the second half of the film, a surprise – none other than Teodor Corban, in what was probably his last film role, playing the owner of an auto garage. And what a superb film for him to have had his last performance!

Although it’s set in the Brussels of Gastarbeiters, the film does not veer into the well-worn territory of suffering, isolation and exploitation – on the contrary: it emphasizes the humanity of its characters by depicting their moments of calm and tranquility, the small instances and details of everyday life that have the power to gain an almost transcendent aura. See, for example, the gorgeous scenes of Ștefan’s walks through the parks of Brussels, which often feature narrative-stopping sequences composed of shots of the rich flora that surrounds him, telling us that we are always surrounded by so much life, and that all life contains within it both a profound meaning and a sort of lightness of being.

In the second half of the film, a surprise – none other than Teodor Corban, in what was probably his last film role, playing the owner of an auto garage. And what a superb film for him to have had his last performance! Though small, his role contains an extremely moving monologue, especially in the context of his passing, strongly reminiscent of Corban’s performance as Constandin (Aferim!) in his moments of introspection and grief. At the very end, the credits dedicate the film to his memory – and what a perfect tribute it is.

***

19th of February: Day 4

A walk-out, a movie like a dream and a bird with clipped wings

Today I managed to get some rest in the morning and to take a walk with Pedro around the neighborhood, where we stopped for a well-deserved breakfast at a neighborhood bakery. Then follows my first screening of this year’s edition at the Berlinale Palast, the first big cinema – as in, 1,000+ seat capacity – I stepped into, back in 2018. I remember the first time that I was there for a press screening, the sensation of feeling absolutely overwhelmed when I noticed that I was being surrounded by so many people. A little ant in an enormous anthill. Pedro is going to see De Facto, in the Forum, and I made a choice that I’m not quite sure of – I’m either going to like it a lot or dislike it just as much – Ingeborg Barchmann, Reise in die Wüste, by Margarethe von Trotta.

The second variant is quickly confirmed: it’s a Hallmark drama (filmed as such) plays on the screen, in which this enormous poetic figure is exclusively portrayed in relation to the men in her life, and both she and they are reduced to mere caricatures. See, for example, the great Max Frisch, the mind behind Homo Faber and Mein Name Sei Gantenbein (incidentally, an appallingly kitsch scene suggests that the genesis of the latter novel occurs as a result of a speech given by Bachmann, and is explained in the most primitive terms), who is boiled down to a mere good-for-nothing that spouts platitudes like “I’m fascinated by your mind” or proves himself capable of the most primitive jealousy.

Which is not to say that Frisch wasn’t capable of horrible things in his relationship with Bachmann (see her novel Malina, also a successful adaptation by Werner Schroeter), but that it’s inexplicable that this script sounds like it was written by a teenage girl, given that there is an extensive extant correspondence between the two that could have provided material for their scenes. As for Bachmann – played superbly by Vicky Krieps, a bird in the cage in this film – we get an ample taste of her suffering, and much less of what made her one of the biggest names in postwar German literature.

Finally, I decide to leave the theater after an absolutely imbecilic and racist scene that turns my stomach: Bachmann is seated in a cafe in Egypt, alone, in her impeccable chic clothes, and two young Arab men stare at her, then approach her in the most sleazy way imaginable. And the two don’t speak English – so the script thinks it best to structure the conversation between them on the principle of “me Tarzan – you Jane”. Just horrible.

Although it’s tempting to say that Forms of Forgetting is a sort of meditation, or a test of endurance, it is much rather a film that plays with that ineffable something that lies at the border between conscious and subconscious, dreamlike and rational, a film of incredible tenderness.

Good thing the next film is just the cure for such an experience – Burak Çevik’s Forms of Forgetting. An essay-film that uses a free discussion between two actors, Nesrin and Erdem, as its narrative skeleton, touching upon everything from their dreams, their experiences in therapy, to their former relationship as a couple, always confronting the idea of remembering and not-remembering (which, Nesrin says, quoting from Marc Auge, are not necessarily two opposite things). Over the course of their discussion, Çevik weaves a tapestry of images reminiscent of Tsai Ming-liang’s documentary films: liminal spaces in Istanbul (including the site of a future art museum, where this film will be shown in some years), frozen lakes, greenhouses, a laptop playing a Stan Brakhage film. The very un-spectaculary nature of the imagery tests in the viewer in it’s probind of the concept of memory, of retention/attention, of internally processed external sights. Although it’s tempting to say that Forms of Forgetting is a sort of meditation, or a test of endurance, it is much rather a film that plays with that ineffable something that lies at the border between conscious and subconscious, dreamlike and rational, a film of incredible tenderness.

And one last film for today – Malika Musaeva’s The Cage is Looking for a Bird, the debut of a young Chechen-born filmmaker, who was a war refugee as a child. An extremely fragile film in the context of the invasion of Ukraine – a French-Russian co-production, made under the wing of Alexander Sokurov’s production company, so it’s automatically marred by the moment independent if its own will, even though it’s a film that is deeply critical of Chechen society and its patriarchal traditions.

Shot on grainy film that often turns its lens towards bucolic landscapes, The Cage… follows a year in the life of a girl named Yakha, who lives in a village that is seemingly timeless – although she is 17, she is still visibly a child, one with rebellious ways, and her favorite activity is to walk the hills that surround the village with her best friend, Madina. But their heavenly life is about to come to an end – they’re reaching the age of marriage, and their only choice is either to accept an arranged marriage, or to willingly choose a (random) boy from the village and ask him to marry them, in order to escape their parents’ plans for them. A well-trodden terrain – but what is special about Musaeva’s approach is that the universe she weaves is almost exclusively female (rarely do we actually see a male character, they’re much rather referential), with all of its tenderness and contradictions. Yakha’s mother has accepted the “cross” she has to bear with great difficulty, but encourages her daughters to go down the same fatalistic path, pushed from behind not so much by tradition as by the need to survive in a system that has the clearest possible coordinates (deep poverty, patriarchalism). Neither a didactic film, nor one that in any way sugarcoats the social realities on the ground (perhaps it only just romanticizes growing up in the countryside), but it’s one that is executed very well, perhaps too well. Still, a notable debut.

At the end, we try to go to a party – but after a long drive towards the east (an occasion to see the East Side Gallery, with my favorite piece of street art in the world – My God, Help Me to Survive This Deadly Love), we run into one of Berlin’s famous eternal entrance queues. Luckily, just as we’re about to leave, good friends Irina Trocan and Sasha Gabrizova come out, and we chat with them for a while, until some new acquaintances pick us up for a consolation beer at Tante Emma, a nearby bar that seems to be straight out of Fassbinder film. And then off to bed.

***

20 February: Day 5

A reincarnation, a social transgression and the beginning of a cold

In Berlin, it’s either a sunny day or a very rainy, windy day, no in-betweens – and today is one of the latter. Today (and only just today, to my great shame) I’m going for my first-ever screening at the Akademie der Kunste on Hanseatenweg, a historic location of German cinephilia: this was where the legendary film curators Ulrich and Erika Gregor founded the Freunde der Deutschen Kinemathek in 1963, which used the venue for seven years in order to screen important films from the history of global cinema as well from interwar Germany – the same Gregors who later founded the Forum and Arsenal. I feel a pang in my chest at the thought that Harun Farocki had once seen films on the same screen that I was just about to watch; a feeling amplified by the academy students who were passing smoothly and carefree through the foyer.

On the menu: Lois Patiño’s Samsara – a public screening, introduced by the artistic director of the Berlinale himself, Carlo Chatrian – one of the films I was eagerly anticipating before the festival, this third feature of the young Galician filmmaker, who was present at the festival three years ago with his sophomore film, Lua Vermella. Working once more with non-professional actors in a docu-fictional format, where the boundaries between the two are often imperceptible, Patiño turns a patient and healing gaze at a school of Buddhist monks, shot on 16mm film, which perfectly tailored for a film with such a strong chromatic palette, often enhanced in sequences where he superimposes religious illustrations over the frame.

The narrative is almost minimal – we see the daily life of this isolated community, where young people of various ethnicities from Laos often come to escape from impoverished home environments. From this observation emerges the fictionalized story of a young man who pays daily visits to an elderly woman who is on her deathbed, in order to read her some verses about reincarnation and to prepare her for the soul’s journey after death. And, quite incredibly, Patiño makes a huge gamble and decides to use the means of cinema to depict this journey, in a sequence that lasts for around ten minutes: and giving away any spoilers (just to say that this must be watched in a cinema), all I can say is that this amazing sequence is a mixture Lettrist current, the inter-dimensional travel sequence from A Space Odyssey, as well as the turning points in El auge del humano and What Do We See When We Look at the Sky? . An absolutely incredible viewing experience, something I don’t think that I’ve ever experienced in a cinema – at least not like this. Without a doubt, Samsara is the best film of the entire festival so far.

In between the two films, a quick visit to the offices of Filmgalerie 451 – both production company, film distributor and DVD boutique – a good opportunity to feel like I took a peek at the famous Criterion Closet (amazing titles: Marseille, Blissfully Yours, a Pasolini box set…) and to pick up a copy of Counter Gravity, the definitive volume on the works of the great German experimental filmmaker, the figurehead of architectural film, Heinz Emigholz – a directors whose works unfortunately haven’t been seen by many in Romania.

Then, back to the AdK for the second film that I planned to see in the diasporic film retrospective: Ordnung (1980) by Sohrab Shahid Saless – an Iranian filmmaker who took refuge in Germany in the mid-1970s. A film that’s very different from the retrospective’s previous one: extremely rigorous in its formality (its shots are carefully, often geometrically composed), in which we follow citizen Sladowsky, a very strange fellow – in the first scene of the film, we see him walking down a deserted street, stopping, then shouting „Awaken! Awaken!” until he succeeds in waking up the residents. Sladowsky – whom we get to understand was once a civil engineer, but hasn’t worked a single day in years – is not so much leeching off the back of his increasingly exasperated wife, as he is a man who seems to have decided to completely detach himself from the norms of society: he takes long walks but also avoids a lot of places (notably, the employment agency), feeds animals and plants with cigarettes, writes strange poems, and stares longingly at the cashiers from the grocery store. The question quickly arises – what is up with this man? Is he an eccentric? A nutjob? A severely depressed person? Or is he quite simply someone that consciously and obstinately violates the number one rule of every extant social order: the desire to work and to be productive? With a final chapter that takes a harsh look at how society pathologizes any individual who ever so slightly deviates from the norm, it is precisely here that Ordnung shows its diasporic gaze: in the way it creates a character that society does not want to assimilate, except by force.

Although I had a third film planned for today – Eastern Front, by Vitaly Mansky and Yevhen Titarenko – and plenty of people to see afterwards, during the screening I feel that a cold is starting to set in. Oh well, an anticlimactic ending for today’s diary entry – I hop onto the S-Bahn and arrive home by 10 PM, something I don’t think I’ve ever done at this festival. Bummer.

***

21 February: Day 6

A Greek tragedy, a Finnish comedy and a special part of the soul

The big day’s here: this morning we’re watching Music, the new film by Angela Schanelec, and tonight’s the screening for In Water, the new Hong Sang-Soo. So we get up at 7 am in order to get to the Palast on time – and, my esteemed audience, just to point out how important this is to me, I must begin by saying that there’s not a lot of things in this world that are capable of getting me out of bed this early.

Like many of Angela Schanelec’s recent films, Music is simultaneously very simple and very difficult to portray in descriptive terms: it’s a companion piece to her 2016 gem, The Dreamed Path, and it’s not just because of the fact that both films traverse both Greece and Germany over the span of several decades, without giving any specific details about the temporal setting of the narrative. Rather, it’s a correspondent that has an uplifting final message, in contrast to the fatalism of the previous film, though it contains within it a great deal of tragedy. Tragedy that is rendered in Schanelec’s distinctive allusive manner, one heavily influenced by Bresson, a filmmaker whose only true contemporary heirs are herself and Pedro Costa – an affirmation of the (f)act of living, of deciding upon it in its favor. The titular music takes its time to arrive (just like the dialogue: the its second line is heard about 30 minutes into the film, not long before the first musical moment), but what an incredibly cathartic role it plays here: from Händel to modern folk in the vein of Nick Drake and Elliott Smith, hinting upon the film’s major themes while also rendering them even more elusive. A very free film – like all of her films. I think that it has a good chance at winning the best direction award; but it really depends a lot on the jury.

After the screening, we grab a coffee with Cristina Iliescu and Dora Leu, who is participating in this year’s Berlinale Talents. Then we run over to Cubix, not before stopping at a Georgian food truck for a Khachapuri, one of the best dishes in the world. Having nothing to see, we go in to see the Finnish film in Encounters, Mummola – a dry comedy about a family that spends Christmas together (and, of course, it’s a disaster), the kind where grandpa gets extremely drunk (but he’s the only actual human in the entire picture, including the kids). It’s an okay movie, but I’ll probably forget that I ever saw it in a week or so. Maybe except for one scene that made me split my sides laughing: at one point, the family’s teenager storms out and goes for a night ride, while blasting on full volume the number one anthem of teens that want to force themselves to feel sad, The Cranberries’ Zombie. Absolutely magnificent.

Then I enter the third shorts program with Oana Ghera – nothing to see here, as was the case with program five, which I even forgot to mention in my diary two days ago. (Save for Back, by Yazan Rabee, which explores the continual trauma of Syrian refugees, more than a decade after the Arab Spring – a film without the unnecessary meanderings that I witnessed in most of the shorts presented in competition, both highly topical and well-contained from a formal perspective.) We catch a gorgeous sunset as we leave the screening, and then I head back to Potsdamer for some Forum shorts at the Kino Arsenal.

Before the last film of the day, we run into our new friend from the States, Edo, at The Barn – we discuss the festival landscape in our respective countries, and the work of festival curators and critics; at one point, Christopher and Daniela join us, and we all set together for the screening of In Water. By the end, I get the feeling that not many people liked it – quite a number of walk-outs, outside, some say that it’s his worst film, and others make some concessions while agreeing. made concessions and say they liked it a bit even so, others that they didn’t like it at all. (The only one who seems to see eye to eye with me is Dora.) This leaves me a bit perplexed – clearly, I’m extremely fond of Hong Sang-Soo’s body of work, which I also associate with some of my happiest moments in the last 5 years, so maybe I’m not capable of being impartial.

It’s certainly his most minimalist film, which is the natural result of the process of this filmmaker who has distilled, narrowed down, and refined a highly distinctive auctorial method and system over the past decade. And of his films about artists, this one is the most explicit in discussing their creative process: we witness the shooting of a short film, in a very free manner, by three young people (an actress, an actor turned director, and a director turned cinematographer). Yet a deeply autobiographical offering – not just in terms of said free manner, based on spontaneity and trust in the organicity of the process, nor in terms of the soundtrack (composed and performed on guitar by Sang-Soo himself, joined by his partner Kim Min-Hee on vocalis), but also of image: rumor has it that the filmmaker has gradually begun to lose his sight, and most of the film’s shots are blurry, to a lesser or higher degree.

To me, however, this blur also contains within itself a different meaning: a message about an immediate reality whose perception is beginning to fade, like a slowly disappearing memory of youth, its simultaneous vitality and melancholy. I’ll definitely want to see the film again, but I feel that this really DIY film (directed, written, edited, produced, etc. by the same man) has already nestled itself in a special place in my soul.

***

22 February: Day 7

A morning in bed, a change of face and an invasion

My cold is back with a vengeance. I melodramatically tell Pedro to go on without me [to the screening of Petzold’s Roter Himmel]. I’ll see how today goes, and how much I’ll be able to get done, but all I know for the moment is that I just wanna lie in bed with our host’s black labrador, Guy.

I manage to get some sleep, write a few thoughts about yesterday and get out of bed to go to El Rostro de la Medusa, the second feature film by Melissa Liebthal, one of the most prominent figures of a new, young generation of Argentine filmmakers that has taken the festival sphere by storm with its experimental-minded, archivistic approach. This is her first fiction feature – admittedly one that’s deeply self-referential: at the center of the film we have Marina, a young woman who one day wakes up with a different face. A Gregor Samsa-like transformation that triggers an identity crisis (including a legal one), but that is treated on a comedic, light-hearted tone – and on the fringes of the main narrative (in which Marina either tries to recover her old face or, conversely, uses her new face to create another existence), Liebthal weaves in animations and archival footage that explore concepts such as the faces of animals, biometric identity, and generational traits.

What is interesting here is that this lost face, which we only see in photographs (some of which also appear in her previous film, Las Lindas, 2016), is the filmmaker’s own, thus creating a reflection about cinematic self-fiction and how it can be used in speculative ways: after all, in an age of imagery in which many filmmakers use the means of cinema to stage their own lives and anxieties (Ivana Mladenovici, Sofia Bohdanowicz), it is fascinating to see how said means can be put in the service of a premise that can be more than just simply realistic.

I’m still feeling pretty sick, so I cancel a ticket (for Luke Fowler’s film – already scheduled at other international festivals, so I’m hoping for another opportunity to see it) and go looking for Pedro at Potsdamer. We take it easy. We grab a farewell coffee with our good friend Sasha G., who’s heading back to Prague, then go for a Käsespätzle with a filmmaker P. met in Mar del Plata. I’m still recovering from the dizziness of the cold, so we go for a screening of Art College 1994 (dir. Liu Jian) at Cubix – one of the two animations in the official competition. Using rotoscope, the film follows a handful of students that discuss everything from their dating lives and Kurt Cobain’s death to the tension between traditional Chinese art and modern conceptual art – but without much substance. It really comes across like one of those Newgrounds flash animations from the 2000s, in a way.

So there’s not much to regret when we leave the screening half-way into the film and cross the street over to the Arsenal, where the world premiere of Graeme Arnfield’s essay-film Home Invasion is about to begin. I met Graeme last fall at BIEFF, where he presented his latest short film, Pervading Animal – about the history of computer viruses and their conceptualization; this notion of historicizing modern technology also permeates this new film, which, in five chapters, traces the rise of modern doorbell systems that have built-in cameras and microphones, as well as the Luddite movement that tried to resist industrialization in the 19th century. A genealogical and generative piece, structured around five historical figures (including D.W. Griffith), using the same narrative structure as a binding force: a character waking in the night from a nightmare, facing paranoia and fear in relation to their private property and the outside world.

We see the images in the film as if through a viewfinder: in a circle, with a vague fish-eye-like distortion, showing diagrams from technical patents, found footage from networks where doorbell users users upload their material, fragments from horror films and etchings, all woven together through text-over. At the Q&A afterward, Arnfield (with much humor) says that “It’s the old story about documentaries: I wish this film didn’t have to exist”; though existentially dreadful, Home Invasion is an exemplary deconstruction of all the technologies that promise users more safety, but only deliver more horror in return.

After the film, I stay behind for another beer with Oana while I wait for Pedro to come out of the premiere of João Canijo’s Mal Viver – which he says is very good. Maybe I’ll catch it tomorrow – our last day already, which is absolutely surreal.

***

23rd of February: Day 8

Two films from the retrospective, a final walk, and an early flight

We catch up on some sleep in the morning – after I finish writing yesterday’s entry, we head to Alexanderplatz for one last round at the Berlinale, with only heritage films. I didn’t catch a ticket for Suzume or for any of the films I missed these past days, the festival is already starting wind down (the market in Alexander Gropius Bau, which I didn’t manage to visit this year, has already closed down) and I’ve pretty much seen most of what I set out to see, anyways.

So we’re off to a screening of the freshly-restored A Rainha Diaba (1974, dir. Antonio Carlos da Fontoura), an insane Brazilian B-movie, like Mean Streets on acid – it features a queer drug-dealing mafia gang that is looking for a scapegoat that would go to jail in their stead, while facing internal power struggles. Subversive in the way it represents hippie culture and the queer community of that era, yet extremely weak when it comes to its action movie aspect (people falling backwards awkwardly and histrionically after being shot, women getting served corrective beatings, seventies TV show imagery). Inside the cinema, I catch a glimpse of Irina Margareta Nistor and amuse myself at the thought of her dubbing a clandestine tape of this film in the eighties.

After the screening, one last lunch where we can take advantage of the fact that Berlin is quite probably the culinary capital of Europe – we settle on grabbing a Bánh Mì from a small Vietnamese place. We have coffee with a filmmaker friend of Pedro’s, who urges us to visit the Pro Qm bookstore, which he tells us is the best in town, so we follow suit: it has a huge and specific offering of tomes on cultural theory, film books and architecture. The kind of place you don’t want to leave, but we have to go back to Cubix for Dick Fontaine’s I Heard it Through The Grapevine (1982).

What promises to be a portrait-film of the great novelist and civil rights activist James Baldwin (one of my favorite writers) and a visit he took to the South of the United States in the early eighties is, in fact, a stark and very painful landscape of an America in which the desegregation of people of color was done only on paper, with a mythology of the movement that covered up the brutal realities of ghettos, prisons and public spaces. Baldwin is much more of a liaison: mostly between the camera and various black community leaders who express their reservations, even disenchantments (“In a way, it’s actually much worse now,” someone says at one point), whom the writer listens to with eagerness, using his stature to give them visibility. A shocking moment in the film shows a public conference where he is a keynote speaker, and a racist hijacks the frequency of the loudspeaker frequency to threaten him: Baldwin is initially stunned, and then makes a spectacular comeback – “whoever you are, even if you were to assassinate me in the next two minutes, the truth is that it doesn’t matter what you say, because the doctrine of white supremacy has had it’s hour, it’s over!”.

What a film to end my Berlinale – we say goodbye to Danny and Darren in front of the cinema, stop to pick up some last gifts and to bid our farewell from the Palast at Potsdamer, and one last dinner at Lon Men, then we run back home. We thank Christi and Alex for hosting us, and nap for about an hour or so, before heading off to the airport for our plane, which should take off at 6:15 AM. Exhausting, but totally worth it.

24-26 February: Epilogue in Bucharest

I get little sleep on the plane – some turbulences, the pilot makes a lot of announcements, etc. Upon arrival, the shuttle bus accidentally drops us off at a boarding gate instead of border control. We have a good laugh, get back on the buss, pass quickly through passports and go to grab the airport bus, where we see around half of the Romanian representatives at this year’s Berlinale – the team of Mammalia, actress Ioana Chițu (present in Talents), some other people. We grab some merdenele from the cornerstore for breakfast. And then we fall asleep.

*

I wake up. I have an online editorial meeting. We order food. Some laundry. We catch up with some screeners. And then we fall asleep.

*

I wake up. I clean the kitchen and bathroom. A screener of Disco Boy. It’s a bad remake of Beau Travail. I fall asleep.

*

I wake up. I dreamt that there was been a fire in the basement of Cinemateca Eforie, killing many firefighters died, and that we had to take shelter in an apartment in the block of flats above, looking exactly like in the seventies, and seemingly inhabited by the ghost of its past owner, a former movie theater worker. What the fuck. We order food.

We watch the closing ceremony of the Berlinale. It looks like it’s snowing in Berlin. Radu Jude wraps a freezing Kirsten Stewart in his coat on the red carpet. The short film I liked the least wins the Golden Bear, alas. Great results in Encounters – prizes for Samsara and Here, amongst others. The results of the Official Competition look very good, as well – obviously enough, the grand winner is a film that screened after we left, Nicolas Philibert’s Sur L’Adamant, a documentary: the visible results of a jury that didn’t cave in to commercial pressures (see the Silver Bear for Best Script, which went to Music). I’m very pleased. And then we fall asleep.

Film critic & journalist. Collaborates with local and international outlets, programs a short film festival - BIEFF, does occasional moderating gigs and is working on a PhD thesis about home movies. At Films in Frame, she writes the monthly editorial - The State of Cinema and is the magazine's main festival reporter.