Mar del Plata 38: Cinema and Democracy

A first encounter with the pearl of South American festivals: Mar del Plata, which celebrated its 38th edition, dedicated to both cinema and its role in shaping the free, democratic spirit of citizens – taking place during a tumultuous period in Argentine history.

I have never, in any of my cinephile excursions, witnessed a moment that touched me so much as the one that took place during the Argentine premiere of La Practica, the first film to be released in over a decade by the godfather of the New Argentine Cinema, Martin Rejtman (a moral comedy about modern alienation, as seen through the story of an apathetic yoga teacher whose life slowly, but surely goes off the rails). The massive Astor Piazolla hall of the Teatro Auditorio – an impressive palace of culture built right on the cusp of the Atlantic Ocean – was full of spectators, most of them in their twenties, and all of them started to applaud and cheer in a complete frenzy when the trailer of the Mar del Plata film festival came on the screen: in particular, when its motto came on, “Cine y democracia” (Cinema and democracy). Their sentiments reached an even higher intensity when the next still came on: „Cultura, Memoria, Verdad y Justicia” (Culture, Memory, Truth and Justice).

Feelings that only gained further traction throughout the festival, like a magnetic wave, becoming almost unstoppable by the time the closing night came around: when the vast majority of those who took part in the ceremony, whether they were the festival’s directors or the filmmakers that had won awards across its five competitions, they all used their speeches as a platform to underline the enormous importance of freedom (not just of expression, or creation) in society and, thus, cinema, about how fragile it is in a world that is so polarized, about how it’s important to keep the flame of memory alive in a present where dark specters of the past haunt all corners of the world.

These moments would’ve been overwhelming even in the absence of such a complicated context; and that took place at all the public screenings that I attended during this edition, while certain projections were accompanied by short clips that featured fragments from some of the 700+ films that were censored by the junta in the seventies („Esto es lo que la censura no te dejas ver” / „This is what censorship didn’t allow you to see”). After all, this year, Argentina celebrates 40 years since the end of the extremely repressive military dictatorship that took hold of the country for almost a decade, between 1976 and 1983 (following other military coups). A dictatorship that, amongst many other tragedies, also caused the festival in Mar del Plata (which was founded in 1954 as a Latin American equivalent to Cannes – just see the list of auteurs and actors that participated in its first years, illustrious and intimidating), which could only be reprised in 1996.

But there’s another reason why this motto was so stringent: namely, the presidential elections taking place this year in Argentina, at the end of four years that have seen the annual inflation rate hit 138% (!), which, along with the crises brought on by the pandemic, has led to the rise of one Javier Milei, a far-right libertarian with an extremist agenda, and who has made it to the second round of voting, alongside Peronist candidate Sergio Massa (who is the current Minister of Economy, so not exactly the best choice; his speech at the festival’s opening ceremony was not without controversy). Many compare Milei to Trump and Bolsonaro: a very fair comparison, but to a Romanian eye, he is much more reminiscent of Vadim Tudor (all the more so as the scenario of this election seems to be extremely similar to that of the Romanian elections in the year 2000).

I’m making this parenthesis because it’s not, in fact, a parenthesis: it’s a preface, a very necessary explanation that allows one to gauge the vital pulse of the festival. Of course, one could write at length about how young the city is; how its inhabitants are spending the beginning of summertime outdoors (especially at the beach); how one out of two people is going around holding a cup of mate in one hand and a hot water thermos in another; how people dance to tango in the Plazoleta Almirante Brown and listen to the matches of Boca Juniors over the radio; how the Argentine accent has its particular inflections (ll – read as dj or dz); about how delicious the country’s two most popular deserts are: alfajores and medialunas. But that would mean refusing to see reality for what it is, or substituting it with a more convenient version; a gesture that would contradict any imaginable ethos of cinema.

*

I came to Mar del Plata to serve on the jury of the Estados Alterados section (named after Ken Russel’s 1980 body horror, Altered States). Curated by programmers Marcelo Alderete and Paola Buontempo, the section is dedicated not so much to cinematic experimentation as it is to exploring a way of making cinema that lies outside of the norm, beyond the narrative and aesthetic reflexes that can be found in the vast majority of modern cinema: an eclectic selection of features and shorts from around the world (with a strong focus on Latin American cinema, as it should be), operating in various formal registers – from structuralism and found-footage to adaptations and dramas with atypical approaches. A few of the films I wrote about at the time of their release (such as Orlando. Ma biographie politique by Paul B. Preciado, or Wang Bing’s Youth – Spring); so, I’ll devote a few lines to the titles that impressed me most in the competition (which is not to say that the titles I won’t discuss at length aren’t deserving).

I’ll start with one of the highlights of this year – Eduardo Willams’ The Human Suge 3 (which was also screened at this year’s BIEFF), which had its world premiere this summer, at the Locarno Film Festival. As I was watching it on the big screen, a playful thought crossed my mind: this film would cause an orgasm to Manny Farber, a heart attack to Gilles Deleuze, and a sweet realization for André Bazin – that his concept of “total cinema” has finally been rendered concrete. What Williams does here (expanding on his bi-camera structure in his 2019 short, Parsi) is to create a device that, at its core, is profoundly realistic (through his use of a 360-degree camera, through the way he records his performers amid situations and conversations that are oftentimes mundane, yet infused with a certain feeling of angst and escapism). And, like any device of the sort, it becomes the perfect grounds for it to be destroyed from within: from a certain point onwards, the characters (initially spread across three countries: Sri Lanka, Peru, and Taiwan) begin to intersect, their actions begin to reverberate in echoes and to spontaneously repeat themselves, the urban environment gives way to the (super-)natural – in short, all the conventional rules that govern time and space are not just destabilized, or broken, but outright reset by Williams, in a film that turns the queer concept of fluidity into its fundamental tenet.

Lying at what is seemingly the opposite pole of the experimental spectrum, Sohn Koo-Yong’s meditative Night Walk is a splendid demonstration of how an extremely simple construction – a series of nighttime shots filmed in Seoul, with occasional overlays of either watercolor drawings or poems and haikus – becomes a fertile ground for both relaxation and transcendence, as well as sheer freedom of interpretation. This is a film in which “nothing happens” – it’s pure observation and contemplation, heavily steeped in Taoist concepts (harmony, the balance between earthly beings, the mysterious and enigmatic ways of existence). At the same time, it’s a film with absolutely no soundtrack whatsoever – what accompanies the screening is the sound of the spectators’ breaths, the rustle of their armchairs and clothes, and some little other sounds here and there, which is something that I believe is superb. And like any work functions like a balm, it works only, and only if one manages to chase away the intrusive, anxiety-inducing thoughts of everyday life, allowing yourself be to carried away by the delicate thoughts and frames in Koo-Yong’s careful weave. (This was very easy to observe in the cinema: those who stayed to the very end were spectators who managed to either focus or enter a meditative state; the anxious, the restless, the impatient and the hurried walked out, one by one.)

One could say that Maryam Tafakory’s latest short film, Mast-del, is also a meditation – but not one of tranquility: instead, it arises from a searing fusion of the personal and the political, which deals directly with the violence faced by women who are forced to live under the Khamenei regime. As in her previous film, Nazarbazi (2022), Tafakory uses found footage (either from historic Iranian films, or anonymized personal archives) onto which she operates textual superimpositions, constructed a narrative intimately bound with the idea of desire – and the impossibility of its affirmation (both literally, and as representation – and especially when it concerns women) under the dictatorship. A desperate scream, drowned out by the jaded nature of habit, and the need to survive a system that dominates and suppresses even the most innocent aspects of everyday life – Mast-del exposes all these feelings in a much more poetic, percussive and enduring way than any narrative film ever could.

The edition’s biggest surprise, to me – and was the film that we quickly, and unanimously agreed to award our main prize – was Malqueridas, the debut feature of young Chilean filmmaker Tana Gilbert: an extraordinary found footage film constructed from images that were shot in secret (and therefore illegally) by the inmates of a women’s prison. Beyond its main narrative – a collage of testimonies from several women, collected within a single character, that explores the tragedies of these lives, along with the moments of solidarity, sorority, love, and relative freedom that are born in the community of the penitentiary –, what is striking about this film is its imagery: shot on cheap mobile phones, their tiny, pixelated lenses also capture the drive of these women to document, preserve moments that one would imagine they would have wanted to forget.

See, for example, this extremely touching footage of fireworks on New Year’s Eve, shot from behind bars – everyone has the impulse to conserve their ephemeral image, no matter where they are, no matter the circumstances they face; on the opposite side, we have images of moments that cannot be allowed to go forgotten: candid photos from the first months in the lives of babies who were born by incarcerated mothers. But, what is even more striking is the act of saving these images – not just through the mere gesture of making this film, but also by transposing the materials onto film stock (the supreme act of preservation): shot on telephones that shouldn’t have been there, that could have been confiscated and destroyed at any time, or lost as a consequence of technological degradation, or due to disposability of their format (see, especially, the footage culled from video calls, eminently ephemeral). And from here onwards, one can easily trace a parallel with the way that the authorities treat these women and their destinies. Malqueridas is yet another revelation of the Latin American found footage scene – one of the most interesting ones in contemporary cinema.

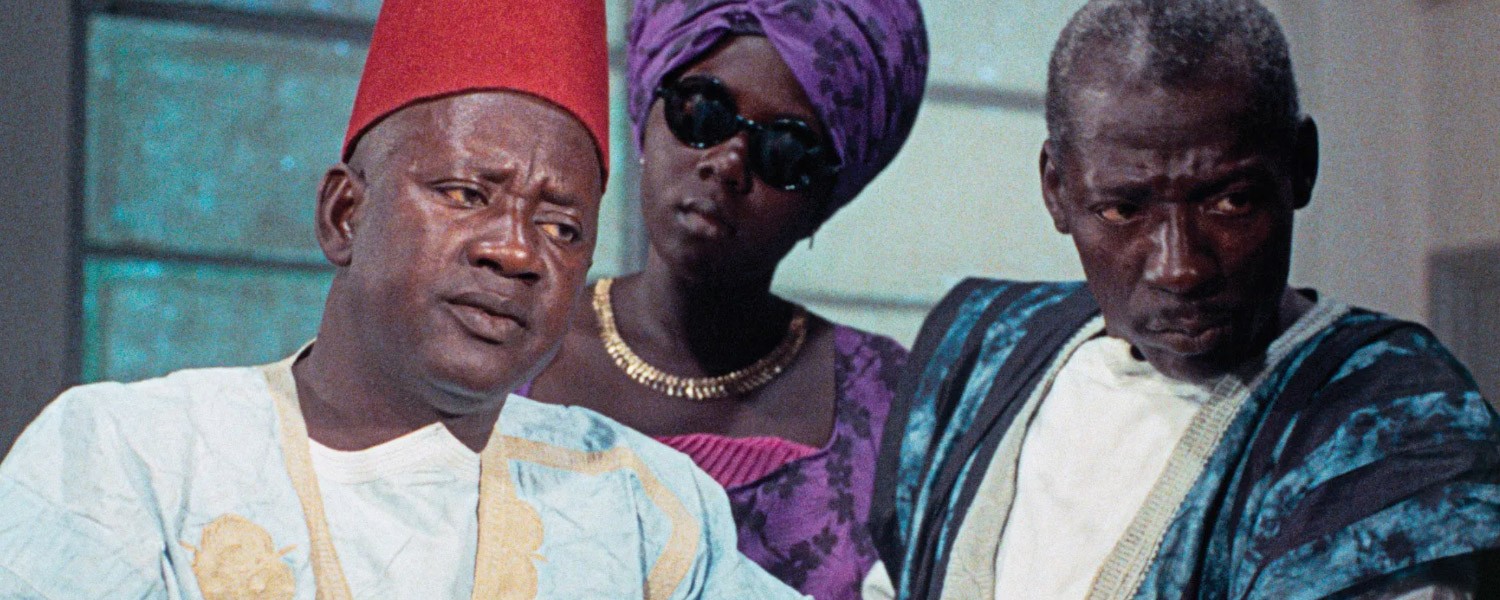

At the same time, I also took a small dive into the rest of the sections presented at Mar del Plata – as usual, keeping a close eye on the festival’s two retrospectives. The first, and largest of the two, was dedicated to the classics of French cinema – from Jean Vigo and Jean Renoir to Agnes Varda and Marguerite Duras, via Alain Resnais and Jean Rouch; from this section, I chose to see the third film by iconic Senegalese-French filmmaker Ousmane Sembène, Mandrabi (1968). I knew much too little of his filmography, to my shame, and that is his masterpiece, Black Girl (1966), one of the greatest anti-colonialist films in the history of cinema – and Mandrabi, his following feature, is the first in history shot in a West African language (Wolof, which is spoken in Senegal, Mauritania, and Gambia).

A comedy of manners that critiques every imaginable front: both traditionalism, which is portrayed as eminently patriarchal and backward, and modernism, which is colonial and capitalistic. A combination that breeds corruption, theft, exploitation, and fraud – but in a manner that is perhaps too heavy-handed, too caricaturesque, too hopeless; it certainly remains an interesting object, but in this respect I prefer Djibril Diop Mambéty’s adaptation of Dürrenmatt’s The Visit (Hyènes, 1992), which is a much more successful social fresco, both politically and artistically speaking. (Another important screening in this section was the restored version of Man Ray’s short films, collected under the title Retour a la Raison and accompanied by a live soundtrack composed by SQÜRL, the post-rock outfit led by Jim Jarmusch – an impeccable restoration that used nitrate reels, which give an incredible intensity to the black and grey hues, especially in the case of the auteur’s signature rayographs).

The second retrospective consisted of a focus consisting of three Georgian heritage films shot during the Soviet occupation, curated by Alexandre Koberidze (What Do We See When We Look at The Sky?), the brightest light to shine on the sky of contemporary Georgian cinema. His selection takes into account both the films’ historicity, as well as the influence they had on himself, as a filmmaker. Whereas the first two films – Merab Kokochashvili’s Great Green Valley (1967) and Aleksandre Rekhviashvili’s The Georgian Chronicle of the 19th Century (1979) – are slowly unfurling dramas that deal with land conflicts (that is, the tension between the natural and the modern, which also doubles as criticism of Soviet collectivization and its exploitative policies), filmed in long, splendid takes in black-and-white, the third of the bunch is wildly different – and clearly, the one that left the strongest impression on the young filmmaker: Rezo Esadze’s Love at First Sight (1975). A Technicolor frenzy about a young Azeri boy, living in a multi-ethnic community clustered around an inner courtyard, who falls hopelessly in love with a Georgian girl from the intellectual class, jumping back and forth between the madness of the streets and the hidden poetry of everyday life – see both the interventions of its omnipotent narrator, as well as its aphoristic intertitles, so playful they verge on the meta-cinematic, that Esadze uses. Love at First Sight has the most beautiful closing scene that I’ve seen this year – this timid, yet extremely free dance of the two lovers, substituting reality with piercing tenderness. (Also: it’s quite interesting to notice that all three films in this focus have “non-endings”; as if to say – there is no such thing as an actual ending.)

To conclude – I experienced this edition (one that, as far as I understand, was much smaller compared to past ones – which only makes me even more amazed at the festival!) of Mar del Plata as a triumph: both of cinema, of the festival’s tireless team, but especially of an inextinguishable desire for culture and freedom. A true miracle – and a feeling that has all the power to erase the fatigue and jadedness that the European circuit often produces, with their line-up full of mediocre films, with their markets full of sell-outs and illusions, with the feeling that they often only seem to be functioning out of inertia. I hope I will have the chance, the privilege to return, at one point: which is something that I wish onto all those who made it to the end of this piece.

Film critic & journalist. Collaborates with local and international outlets, programs a short film festival - BIEFF, does occasional moderating gigs and is working on a PhD thesis about home movies. At Films in Frame, she writes the monthly editorial - The State of Cinema and is the magazine's main festival reporter.