Ryusuke Hamaguchi: Introductory Words for a Filmmaker of Words

This year at TIFF, the 3×3 section was dedicated to Japanese director Ryusuke Hamaguchi and features his films Drive My Car (2021), Evil Does Not Exist (2023), and Passion (2008).

I’ve often been asked why I find Ryusuke Hamaguchi one of the most important contemporary Japanese directors. On one hand, he seems very apolitical, although he claims not to be, and an excellent essay by Emerson Goo on disability in the director’s films astutely observes some political undercurrents. On the other hand, a director celebrated more by film festivals than by local audiences (like it happens here, in Romania) always raises suspicions. “Isn’t he just a festival craze?”

Hamaguchi is no Cannes darling, like Hirokazu Koreeda and Naomi Kawase, who have been making very accessible art cinema for the past 20 years or so. It’s not that he is inaccessible (the Oscar nominations for Drive My Car perhaps prove it best), but Hamaguchi makes a completely different type of cinema, drawn from the independent film scene, difficult to finance – especially in the Japanese context – and one that challenges conventions. It’s a very cinephile cinema, one might say, more attentive to the history of cinema and its language resources than to delivering messages or box-office hits. Although his graduation film, Passion (2008), received much appreciation, including from his master’s professor Kiyoshi Kurosawa, until his international and festival breakthrough with Happy Hour (2015), most of his films struggled to find distribution. A charming scene in Following the Sound (2023), by his colleague and friend Kiyoshi Sugita, shows a movie theatre in Tokyo where only about 5 people are watching a scene from Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy (2021).

“The greatest location in the world is the human face” – John Cassavetes

The answer to why I give Hamaguchi a front row seat is very simple. His characters talk and act like people I know, like real people. Saying this might seem counterintuitive because Hamaguchi creates a cinema strongly anchored in theatricality and leaning towards the literary, with focal points and references belonging to other arts. Intimacies (2012), like Drive My Car, follows the intricate staging of a play on multiple levels. In Touching the Skin of Eeriness (which, if I may digress, features one of Japan’s most versatile young actors, Shota Sometani), the story and camera are dedicated to dance. In Asako I & II (2018) and The Depths (2010), photography plays an important role – in the former more subtly, with a work by Shigeo Gocho featuring a pair of twin girls heralding the doubles in the film, and in the latter more obviously, with the story following a photographer who finds a muse in a male escort.

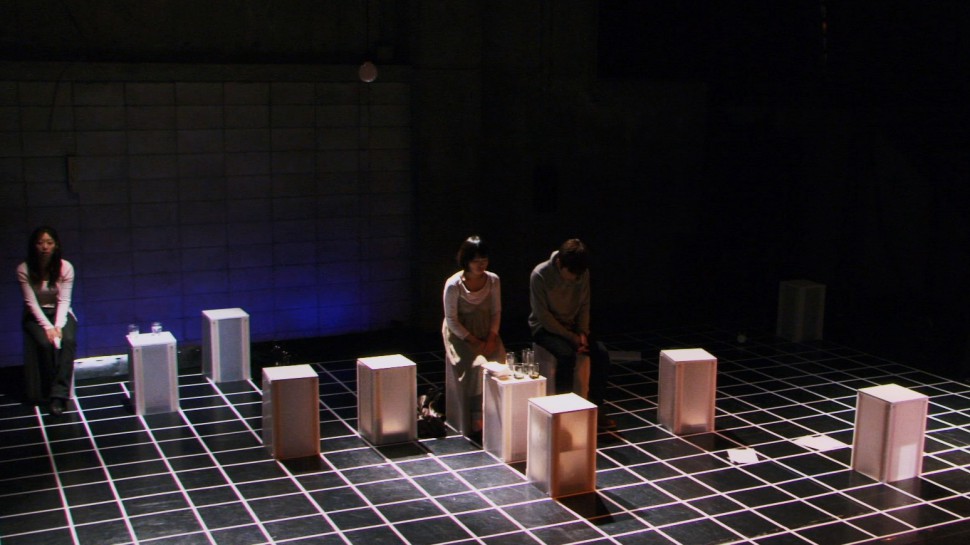

But beyond these elements, Hamaguchi’s cinema always returns to people, to a kind of Cassavetes-like sublimation of the human soul in film, to a screen filled with gestures and words that the camera exposes and renders vulnerable. The comparison to Cassavetes is not unfounded – the director himself cites him as an important influence, always fascinated by the naturalness with which Cassavetes’ characters express their emotions – words and actions often marked by contradictions and whims that never seem artificial. Like Cassavetes, but also like Rohmer and perhaps Hong Sang-soo, Hamaguchi is an artist of conversation and human relationships, of communication and miscommunication that either circumstances or we ourselves create. Proof of that is the long (sometimes up to 15 minutes) and nuanced conversations in Intimacies, between playwright couple Reiko and Ryohei, between them and the actors, and among the secondary characters, all capturing with finesse – and no shortcuts – the challenging act of communication: from micro-expressions to the search for the right word, to misunderstandings, to pauses. In a review of Drive My Car, I highlighted the centrality of the word itself and the act of storytelling, which emphasise the manner and physical act first and only then the message. In both Intimacies and Drive My Car, the reading of the play’s lines matters more than the final artistic product.

Also like Rohmer, Cassavetes and Hong Sang-soo, Hamaguchi is what you might call an actor’s director: he has incredible talent for both working with actors and finding the right actors, sometimes preferring non-professional ones, as shown by the four protagonists in Happy Hour and his latest project, Evil Does Not Exist, where the so-called “forester” Takumi (Hitoshi Omika) is played by the former production manager for Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy. The acting space easily becomes one of improvisation, where reality and fiction intertwine and influence each other – Intimacies provides the perfect example in its first half, where the reading of the text and the staging of the play Intimacy (which Hamaguchi himself wrote) are watched as if it were a documentary; only gradually do you begin to identify the fiction.

Hamaguchi’s interest in documentary is evident in how he very concretely anchors his characters in the generally urban reality they belong to or in his long, unmediated durations that resist essentialization and contraction. Time is allowed to flow, and the world outside the frame continues to exist within it. But this interest in documentary is also present in his work as a very approach – see the film trilogy co-directed with Ko Sakai, about the Tohoku region and the effects of the March 2011 earthquake. Here, too, the emphasis is on interviews and people, with the documentaries focusing mainly on people and their memories of the region.

The New Hamaguchi? “Evil Does Not Exist”

Documentary and ecological disaster linger in Hamaguchi’s filmography: Happy Hour follows the region’s coastline and the tsunami debris in the background, while Touching the Skin of Eeriness contains several references to biology, fish, and natural oddities to describe human relationships and identity issues. His latest film, Evil Does Not Exist, which many have called an ecological parable, perhaps reactivates most strongly the connection to nature, as the story follows a talent company that decides to make a glamping site (“glam camping”) in a picturesque village on the outskirts of Tokyo. Its representatives clash with the villagers, who rightly reproach them for disregarding sanitary measures and their wishes.

Evil Does Not Exist is, however, quite an atypical project for Hamaguchi. It starts not from a script, but from an invitation by musician Eiko Ishibashi – who also composed the score for Drive My Car – to imagine a filmed material for one of her compositions. The collaboration resulted in two films, Evil Does Not Exist and Gift, the latter being a cine-concert that reuses and re-edits the same material, no sound, featuring only intertitles. For a filmmaker who values language and the spoken word so much, the use of intertitles might seem strange, but it’s just another facet of exploring the act of communication and its expressive limits.

What is striking about Evil Does Not Exist is rather its bleak tone and an ending many have cited as more fitting for a Kiyoshi Kurosawa film. Hamaguchi is usually not a dark filmmaker; he belongs more to the Rivettian tradition where paranoia meets playfulness and hazard. Whether it’s the bizarre appearance of a man who looks identical to the former lover in Asako I & II, or the games and chance encounters in Wheel of Fortune of Fantasy, although peppered with tragedy and dark places of the human soul, the filmmaker’s oeuvre is marked by nonchalance, the whimsical nature of fate, and unusual coincidences. Hamaguchi is a director of drama much like Rohmer – drama and intense emotions are present, but dark thoughts never cross into horror or crime territory.

Evil Does Not Exist, along with its companion Gift, changes the course slightly but doesn’t deviate completely. The taciturn Takumi is more opaque than the taciturn Kafuku in Drive My Car, but both demonstrate Hamaguchi’s knack for capturing silence. After all, silence is also a form of language, for it communicates the very absence of communication.

Language is the focus of Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s filmography, whether we are talking about verbal language or the cinematic medium. The Japanese filmmaker tests the boundaries of both, blending fiction with reality and exploring the fictional within the real, making the camera an eternal witness to the performative act. What is the performative act? Sometimes, as Asako I & II suggests, it pertains to the roles we assume in society and towards each other. Other times, as Hamaguchi’s films about theatre speculate, it exists in more concrete terms as an artistic exercise. Metacinematically, it exists in every frame, as Hamaguchi’s camera is always interested in observing how language is articulated – in time and space, cinematically and verbally, heard and unheard.

Hamaguchi’s fame also seems to be linked to the long duration of his films. Drive My Car caused a stir with its three-hour runtime, although Happy Hour surpasses it, being five hours long. It begged the question of why you’d need that many hours for a film. In Hamaguchi’s work, beauty comes from digression, from what others might accuse as rambling. His filmography is a cinema of patience, committed to looking at the non-essential aspects of human life, in which, paradoxically, lurk the microscopic elements that make us who we are.

Graduated with a BA in film directing and a MA in film studies from UNATC; she's also studied history of art. Also collaborates with the Acoperisul de Sticla film magazine and is a former coordinator of FILM MENU. She's dedicated herself to '60-'70s Japanese cinema and Irish post-punk music bands. Still keeps a picture of Leslie Cheung in her wallet.