Aloners. On solitude | San Sebastian 2021

Of all the East-Asian national cinemas that have attracted the most attention across the last decade, South Korea’s is certainly the most visible one. With an industry that has a massive output and a constant presence in the world’s biggest festivals, where it has constantly won the industry’s top awards (from the historic Palme d’Or won by Bong Joon-Ho in 2019 with Parasite, to Kim Ki-Duk’s 2021 Golden Lion winner Pietà, to the small zoo composed of bears, leopards and tigers won by Hong Sang-soo), Korean cinema seems to be living its most successful age since the sixties. But one must acknowledge the fact that, for the most part, the Korean films that arrive onto the international circuit are directed by men – and so, the release of a film such as Aloners, the feature-length debut of young female filmmaker Hong Sung-eun, is more than welcome in this context. However, her film is marred by formal indecisiveness and a series of facile narrative choices which distract from the weight of its main topic: that of contemporary loneliness and alienation.

Loneliness is a topic which arthouse cinema has approached oftentimes across its history, frequently stitching it together with the condition of modernity – from Michelangelo Antonioni’s masterful trilogy of alienation (and especially so in his 1962 L’eclisse) to a fair share of Eric Rohmer’s Comedies and Proverbs, particularly in Le Rayon Vert (1986). And it’s not a coincidence that contemporary East-Asian cinema also often explores this topic, given that the phenomenon of social isolation is much more frequent in this region – starting with Tsai Ming-liang’s early masterpiece, Vive L’amour (1997), and closing off with Wong Kar-Wai’s Chungking Express (1994) and Happy Together (1997). In Aloners, what is particular about the representation of its protagonist, Jina’s (Gong Seung-yeon) loneliness, is the fact that it’s finally shaken free of its connection to her love life, one of the main reasons which are given to explain the solitude of a female (or queer) character. In the tradition of arthouse cinema, and heavily referencing Hong Sang-Soo’s narratives, Hong Sung-eun denies the viewers too many details about her characters’ backgrounds, leaving the approximately two-week-long span of the story to speak for itself.

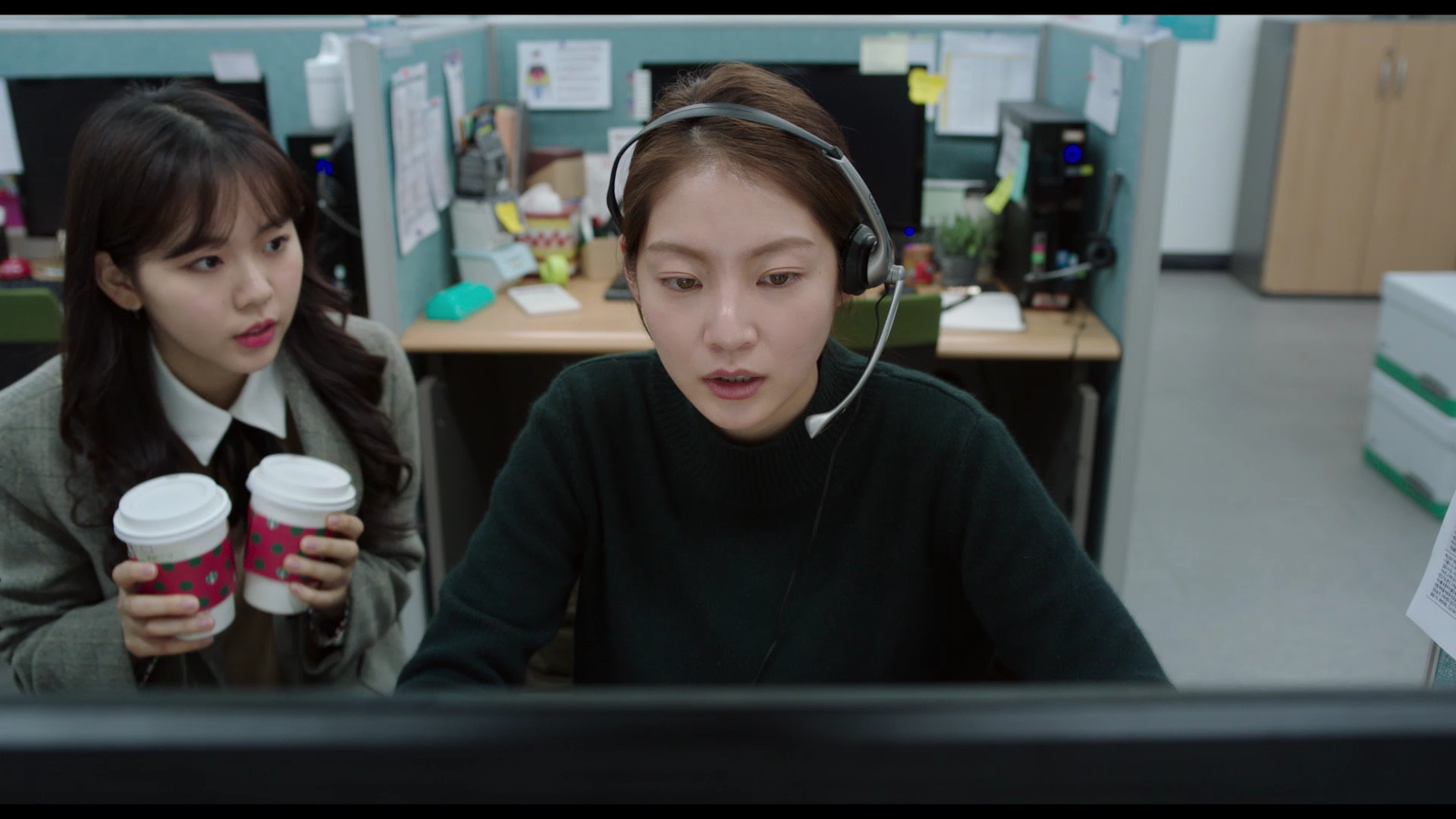

For the better part, Jina’s life is defined by her job, but the problem is that its very nature forces her to be a neutral and depersonalized presence: she works at a call center that takes clients from a local bank, where we discover that she is the most productive employee, although her mother has recently passed away. Aside from her daily commute to work and her solitary lunch and cigarette breaks, all done while staring at her cellphone, watching inconsequential videos (ASMRs or Mukbangs), she sometimes meets her estranged father, but only due to her obligations following her mother’s death. A series of events forces Jina to leave the comfort zone in which she has isolated herself – first of all, her boss tasks her with training a new employee, the kind and friendly Sujin. Second of all, her NEET neighbor dies in a freak accident, crushed by a tower of porn magazines, and makes the national news, making Jina believe that her final interactions with him had, in fact, taken place with his ghost. Last but not least, the protagonist steals the SD card from her parents’ surveillance camera and starts to obsessively watch the last recording of her mother, but also peeks at her father’s grieving, going so far as to even start watching him on a live stream as she’s rejecting his calls.

As I mentioned earlier, Hong Sung-eun avoids the reasons why Jina has decided to almost completely cut herself off from society (but, from the few pieces of evidence that we have, it seems that she took this decision long before her mother passed away). The fact that her work implies working directly with a large number of people offers the filmmaker a chance to outline the sketch of a hostile society – the majority of clients who call in are abrasive and entitled – while also underlining Jina’s complete emotional detachment, as she answers all of them on the same impassive tone, hidden beneath the depersonalized politeness she is asked of in her line of work. Of course, Sujin acts as a counterweight – naive and clumsy, not only is she shaken up after a client manhandles her during a call, but she’s also the call center’s only employee to respond empathetically to a mentally ill man who routinely calls their company.

Jina rejects her younger colleague, just as she rejects her father and her neighbors, keeping her interactions with them at a bare minimum, and appearing defensive whenever someone seems to be getting too close. Unfortunately, even though she seems perfectly content with this lifestyle, however austere and cold it may be, the narration still ends up gearing towards a pretty clichéd happy ending, even if Hong Sung-eun avoids pulling the levers of melodrama as hard as they would’ve been pulled in a traditional, mainstream drama – but it’s more than enough to dissipate much of the emancipatory feeling I described in the beginning.

And for a film centered on a woman who spends much of her life in front of the screen, there are way too few moments in which it explores her relationship with it, let alone question it in a larger, meta-cinematographic sense, a chance that is mostly missed, even in moments in which the notion of voyeurism is at hand (a topic that is much better exhibited in a film such as Edward Yang’s 1986 The Terrorizers). A few shots have Jina staring straight into the camera as if she would stare back at the audience, just as she sees her dead neighbor as he’s having a smoke in front of his apartment; even so, these shots are not tied together by any red threads and have no importance in the film’s endgame, thus never leading to a more substantial questioning of the act of looking or of the cinematic apparatus, rather coming across as simple, momentary artifices.

Although it remains a strong and novel character study, underpinned by social critique and reflection, Aloners is, unfortunately, unable to transcend the status of a mere drama – almost seemingly self-sabotaging the very occasions it opens up for itself.

The European premiere of “Aloners” took place this morning, at the San Sebastian Film Festival, in the “New Directors” competition.

Title

Aloners

Director/ Screenwriter

Hong Sung-eun

Actors

Gong Seung-yeon, Jung Da-eun, Seo Hyun-woo, Park Jeong-hak, Kim Hannah, Kim Mo-beom

Country

South Korea

Year

2021

Distributor

M-LINE Distribution

Synopsys

Jina is the best employee at a credit card company call center. She avoids building close relationships, choosing instead to live and work alone. Jina maintains her solitary lifestyle well until her irritating neighbor, who would attempt to strike up conversations with her, is discovered dead a few days after his lonely death.

Film critic & journalist. Collaborates with local and international outlets, programs a short film festival - BIEFF, does occasional moderating gigs and is working on a PhD thesis about home movies. At Films in Frame, she writes the monthly editorial - The State of Cinema and is the magazine's main festival reporter.