Entranced Earth – Three miserable politicians | Kinostalgia

“Kinostalgia” is the title of a monthly column dedicated to repertory cinema, in which critic Victor Morozov picks well-known or undiscovered samples from the history of film and analyzes them from a fresh perspective. Today you can read about Cinema Novo pioneer Glauber Rocha’s third feature, “Terra em transe”.

“[…] Furthermore, Cinema Novo is a phenomenon of colonized peoples everywhere and not a privilege of Brazil. Wherever there is a filmmaker prepared to film the truth and oppose the hypocrisy and repression of censorship, there will be the living spirit of Cinema Novo. Wherever there is a filmmaker prepared to stand up against commercialism, exploitation, pornography, and the tyranny of technique, there will be the living spirit of Cinema Novo. Wherever there is a filmmaker, of any age or background, ready to place his cinema and his profession at the service of the great causes of his time, there will be the living spirit of Cinema Novo.” (Glauber Rocha, “The Aesthetics of Hunger”)

He was the standard-bearer of Third-Worldism for a long time, and the entire would greet him with open arms. He was the first to resuscitate a cinephilia that was increasingly threatened by sclerosis, one that was incapable to comprehend the path that was to follow after the dissolution of Hollywood studios. He was the one to help entire masses regain their faith that cinema is more than just illusion and glamour, simple shapes tumbling in the void. For those who knew him, he was life fireworks; for others, he was a name that gathered within itself all the contradictions and frustrations of an era, and who ultimately bet everything – by the time he ended up abandoned and sick – on the side of cinema. Glauber Rocha (1939–1981): wunderkind and wayward son of Brazil, the precursor of the movement that was to be called Cinema Novo, a junction between guerilla cinema and the great festival markets, a man that was inexhaustible, like very few are. To resume his riotous life in just a few lines is an exercise in futility. It’s better to start (re)visiting his films because they are great – real tourbillons of telluric force, primitive magic, hypnotic ritual, and epic theater. Amongst them, Entranced Earth / Terra em transe (1967) might be the greatest.

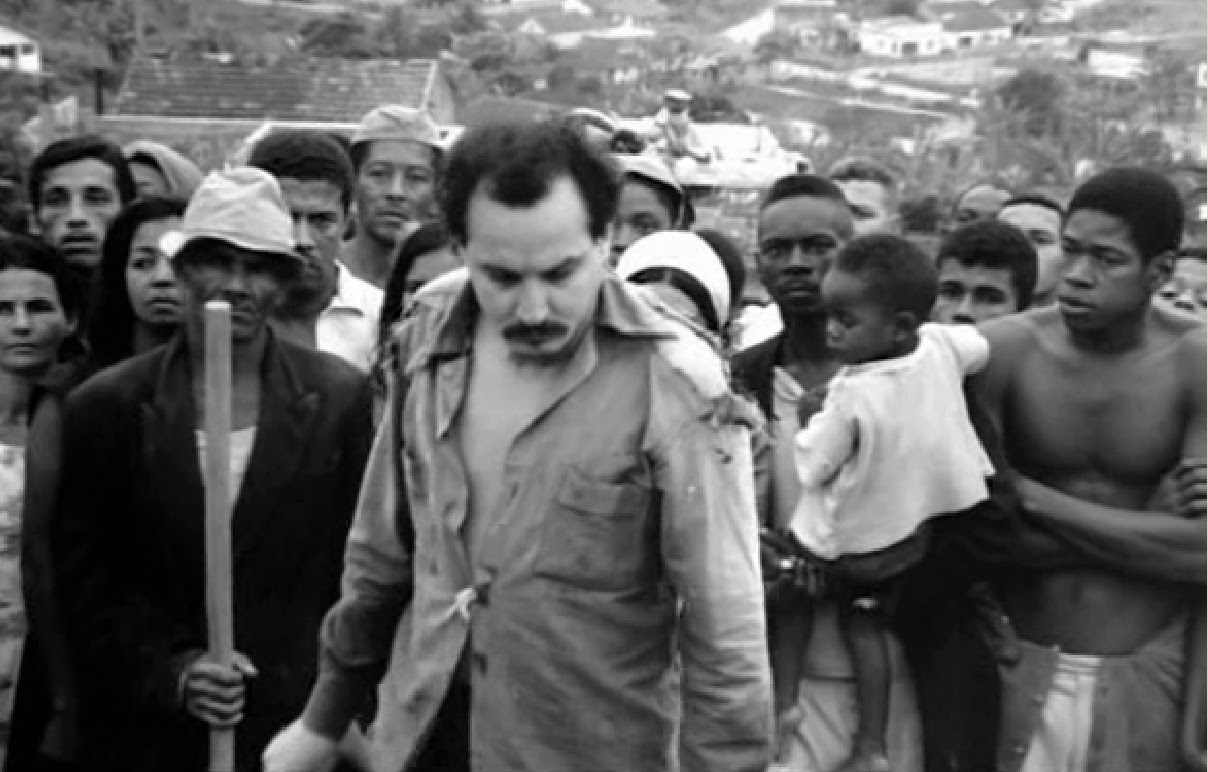

Following an incursion into the mythological, quasi-Western-like past of Brazil, Rocha’s third feature film returns to the present, but in a somehow roundabout way, under the form of an on-the-nose allegory. We are in Eldorado, a land consumed by political turmoil, in which two men are seen fighting for supremacy, from a distance: one is a fascist who is parading around with a cross in one hand and a black flag in the other, isolated from the outside world in his aristocratic palace; the other is a populist who promises nothing short of the stare to the starving peasants, holding ardent speeches within their midst, but who ultimately ends up betraying all of them across the spectrum, and is now threatening with political repression. What unites these two men, both of them lost within their respective air-tight worlds, is poet Paulo Martins (Jardel Filho), a man of intrigue who lies behind the scenes, an engaged artist who dreams of greatness, yet who finishes mired in the dirty waters of corruption and doubt. His rise and fall, both steep, both undeserving, both the fruit of a free-wheeling change of alliances that is bogged down by remorse, are the topic of this film that is ravaged from all sides by unsolvable contradictions and prophetic paradoxes. Rocha’s purely Wellesian awareness, which he shares with the film’s protagonist, compelled him to always probe into the moment’s burning kernel, seemingly forcing him to adopt a similar path to the shaman-filmmaker that was Welles. Something which Serge Daney likened to a rocket: the same whirlwind beginnings, with Welles creating Citizen Kane at 26, and Rocha creating Barravento at almost 24, followed by a momentary silence – both reach the respective peaks of their celebrity quite quickly –, and then an unrelenting dissolution, when both lose mastery over their auxiliary engines, their fuel reserves, pilots, everything. But for those who are willing to believe in them, following in their steps all the way to a Saturnian empire, their incandescence is more than enough. Both of them also show the same fascination for Dionysian destinies – with the distinction that, in Welles’ case, Kane was a megalomaniacal mogul who dreamed to control information, while Rocha’s Paulo Martins is an idealistic poet who dreams of maneuvering the masses’ conscience. As we can see, there isn’t any difference in substance – only an accent whose weight is moved elsewhere.

Truffaut once said that films are similar to their own authors, and it was as if, at that moment, he had just finished watching Entranced Earth. Every time I watch and rewatch Rocha’s film, I’m always stunned by the rigorousness with which each individual shot develops in itself an unstoppable poetic surge. It’s like Rocha, beyond the narrative utility of these images, would have cared only for an imperative view of the mise-en-scene as a reservoir for poetic fuel. Few films come to mind that allow themselves to go along the flow of an all-encompassing exaltation, yet still manage to keep the compass of their obligatory lucidity intact. Rocha seems to have imprinted his very way of being onto this film: easily inflammable and sharp, dreaming yet disillusioned, ravaged by contradictory currents coming in from all four horizons. In an important book that is dedicated to the filmmaker, Sylvie Pierre writes: “His entire oeuvre is thus split between two ways of seeing cinema. The first, which is voluntarist and undoubtedly political, entails practicing cinema «as it should be», for the Third World, for an incensed Latin America, for an affirmation of the importance of Brazilian cinema in the world at large. The other, which corresponds to a passion for cinema that is akin to that felt by a poet, and which only regards himself, yet without ceasing to capture the contradictions that are inherent to an oppressed culture.”

Rocha invents too little in this allegory – it’s more than enough for him to look to here and there, beyond the “goats” and bloodthirsty generals who have ravaged an entire continent across entire restless decades: the traces of the past and the threats of the future are omnipresent. This is maybe why, although none of the names in the story are revealed, that everything – from the tragic figures of the peasants to the gluttonous mugs of the politicians, all the way to the cigars that are always hanging from the corners of their mouths, their bulging stomachs that peak from beneath their ill-fitted coats -, everything has a vaguely familiar air to it, like an anchor that keeps the film tied to a dialectical vision of history. One must see the almost comedic sequences in which the film off-handedly parodies the format of reportages meant to smear political adversaries, powered by a clunky and propagandistic voice-over, that is none the wiser than the machinations of its adversaries. That doesn’t prevent Rocha from losing himself in a series of superb intimate digressions, in which the violence of politics makes space for the violence of love and the immersion in the depths of the era’s social and cultural climate, due to a few liberating sequences shot in a jazz club, that are on the very level of Cassavetes. By letting us accompany a tortured conscience, that is stuck in a constant back and forth from one political leader to another, one woman to another, one wall of his mind to another, Rocha will have affirmed his belief in a cinema that, without sacrificing anything that belongs to the turmoil of subjectivity, can still articulate, record and accelerate the need of a collective popular struggle for emancipation. From an unstoppable urge for utopia, Rocha weaves his film as a poem meant to favor the masses, like a bullet against imperialism, like an image that contains within itself both the traces of subversion and those of self-critique. As Paolo Martin said, in a muted roar of sorts, “When beauty is overcome by reality, we can finally feel how death is converging, even under the guise of life, aggressive.”

Entranced Earth / Terra em transe is available on MUBI.

Title

Terra em transe

Director/ Screenwriter

Glauber Rocha

Actors

Jardel Filho, Paulo Autran, Jose Lewgoy

Country

Brazilia

Year

1967

Film critic and journalist; writes regularly for Dilema Veche and Scena9. Doing a MA film theory programme in Paris.