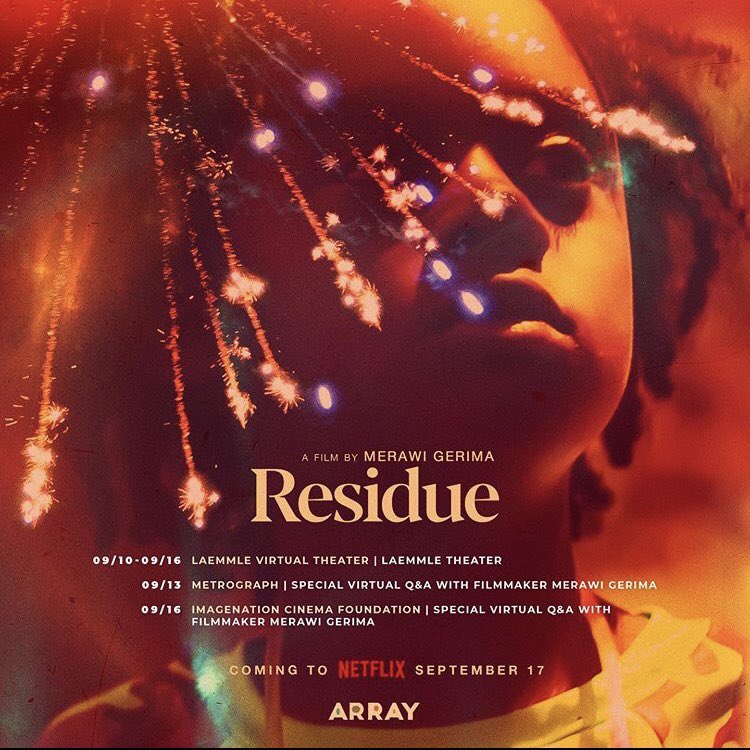

AIFF.4. Residue – Home, on the Field of Armageddon

A young man returns home after a long time. We already can infer – because we’ve seen movies before – that, as in the case of any return, in this case, too, everything will be complicated. The life of the neighborhood has pushed forward, people – be it family or old friends – are the same, but somehow different. Onto the difference between the one that left and those that stayed behind which has, in time, transformed into a deep chasm, director Merwai Gerima constructs an urgent film, which at times is either pugnacious or melancholic, speaking of times that resist passage. I’ll just add that everything transpires in a Black community, and the people that we see are young, angry, and snappy: to play upon a famous slogan of ’68, this film has something to say and it knows precisely what that is. It’s enough for it to become a topical hit, which pushes the right buttons at the right time. Is it however enough for it to be a truly grand film?

Cinephiles are aware that “Gerima” is not an obscure name. You’ve guessed it – Merawi is the son of the great Haile, a theoretician, and practitioner of the so-called Third Cinema, which in the seventies and eighties was blowing up the usual models of representation (of race, class, gender) used by mainstream cinema, showing us facets of Los Angeles that had never been seen before. In Ashes and Embers (1982), for example, we could see how the veterans of the Vietnam War were not all white, and that these people of color, who had yet to have been in the eye of the camera, were living a life that was filled with twists and turns, hidden, suffering, which then had to be mapped out all the way to its darkest corners. Since then – meaning, the peak of the L.A. Rebellion movement, spearheaded by Gerima, Charles Burnett, and Billy Woodberry – things seem to have stagnated, from a social and cinematic point of view. In regards to social issues, this hot and confusing summer has fully demonstrated it, while still achieving to impose the figure of George Floyd as a post-mortem icon that embodied a popular uprising that has yet to quell. Cinematically, with very few exceptions – such as Spike Lee, Jordan Peele, or Boots Riley – one has the impression that the films of the L.A. Rebellion, brimming with sheer life, unpolished and unscriptable, remain a peak that has yet to have been surmounted.

Merawi Gerima seems to choose the middle path between two possible directions: one that is keenly aware of the vicissitudes of living in America as a regular person of color, who is forced to confront “interracial tensions” and the latent racism of society as a whole; and one that captures the need to raise one’s fist and fight to a more just alternative to our current world. That’s why his film has the atmosphere of a mix between emotionally charged moments, which firmly set the plot in the area of topics that have a lot at stake, with parts that ring a sour, dissonant note, which seem to be heavy-handed in restaging prior trailblazing films. The film’s charms and limits have, in fact, something to do with the sensation that the entire project has been written by a hand that is not yet steady and is thus overwhelmed by the massive scope of the problems that it raises. In this vulnerability, which hints at the image of a young man who’s dedicated to addressing everything, to fully exorcise an inexhaustible topic, we may possibly find the key to this film.

To give an example – to burden protagonist Jay (Obina Nwachukwu), who has just graduated and has a plan to shoot a film about Q Street, that place in which he spent his childhood years together with his newly rediscovered comrades, is, if not an idea that is painfully contrived, one that is at the very least naive on part of someone who seems to be much too attached to his own biography for his own good. A drier film would have been preferable, constructed on the exchanges of mostly hostile glances between white people and Black people, in order to enter a fundamentally identitarian experience from the get-go. When the film limits itself to these aspects, the result is impeccable: just take a look at the short sequence in which Jay discusses with one of his friends at night, next to his home, as the image slowly starts to turn blue (indicating approaching police lights) and his friend preemptively takes off his hoodie, even though there was nothing in the situation to warrant such a gesture. In such detail, which is unexplained and barely noticeable, we can see a wound that is deep and hard to discuss, which is doubled by his ability as a writer to take a step backward and to look to the outside. It’s literally what we see in the scene in which Jay is escaping the police after an altercation: the camera slowly runs backward, revealing two white young men who are watching the entire situation unfold from the terrace of an apartment, as if they would be watching a show and were just about to „reach for the popcorn”. Is this little directorial gimmick a bit too explicit and didactic? It could be, but what I can say is that, surprisingly enough, it works. It’s as if, in these moments, Merawi Gerima would become conscious of the fact that this might be the only price one must pay in order to let politics seep into art, nowadays: with the price of being „in-your-face”, which assures us that we can no longer pretend that nothing is happening. Such fragile moments, in which fiction also delivers its residual callouts and anger, are all the best that a militant form of political art, which desires the good of all people, has to offer.

Residue has screened at the 4th edition of American Independent Film Festival.

Title

Residue

Director/ Screenwriter

Merawi Gerima

Actors

Obinna Nwachukwu, Dennis Lindsey, Taline Stewart

Country

USA

Year

2020

Distributor

Netflix

Film critic and journalist; writes regularly for Dilema Veche and Scena9. Doing a MA film theory programme in Paris.