The Mother and the Whore – Blackstar

We’ve all seen it in poor copies, with their increasingly approximate cinematography, as if painted in muddy oils. We knew that, after being exposed to its blackstar radiation, we had to bid goodbye to art’s infancy. „La Maman et la Putain” is now back, fifty years after its release, together with its creator, Jean Eustache, the lodestar of the “cinephile” generation, the one who turned desperation into one of the fundamental reasons why you should conceive to a film.

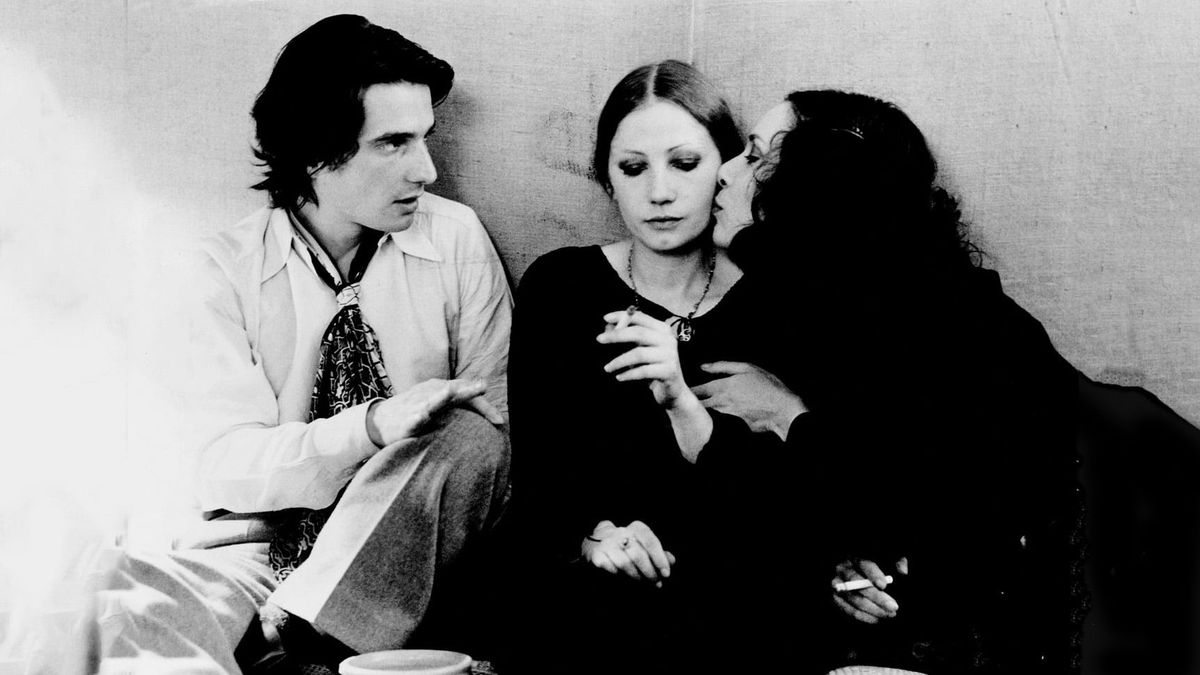

There’s a story in La Maman et la Putain, one without any heads or tails, without any “positive” or “negative” emotions (while still replenished with toxic intrigues), the kind that makes “profession professionals” frown. It’s the story of a man who feels that stories are no longer possible, that we have entered a world where no story can be told any more, because everything is to be sold. La Maman et la Putain is not the first film that begins upon its ending – the break-up of Alexandre (Jean-Pierre Léaud) has already been consummated for quite some time –, but it’s one of the most striking observations about the inability to invent another story as a replacement: three hours and a little while later, Alexandre is stuck once more in the same rut, one that’s even worse. A woman takes the place of another, while a third is there as a simple backup plan; an hour of screening follows the other; a sequence shows us three jokes told by Alexandre in rapid succession, without us having the time to fully enjoy them. The film lets itself sway to the frenzy of accumulation, a sign of creative and social mechanisms that have gone missing in the meantime. Its mute desperation, shielded by the script’s soft cynicism, is provoked by the fear that old structures are no longer functional, and that their replacements are failing to show up: two women are altogether no longer fulfilling of love (one even less); four hour of screening time are no longer the guarantee of a film. And so on.

Ever since Jean Eustache, nobody has ever turned a camera on while feeling animated by the same level of directorial intensity, save for Philippe Garrel. Shot in 1979 and released later, in 1983, L’Enfant secret is the correspondent of Eustache’s film yet in opposite fashion, incessant dialogue ousted by stares weighed down by the unspeakable, its false relational equilibrium of the sexes replaced by an excess guilty of sentiment. It’s no secret that a film like La Maman et la Putain, one even more cutthroat than Jacques Rivette’s Out 1, has been claimed by almost everyone as the greatest chronicle on the aftermath of May ’68, with its aimless youth hiding behind challenges (they “jokingly” indulge in reading Nazi propaganda) and café chit-chat, in the hopes that they will be able to fend off the oncoming onslaught of reality. Fifty years later, the quality of the dim light that envelops each of the film’s frames, wrapping it into a palette of darkened grays – a true case of chromatic sore throat that muffles the cinematography –, reaches its zenith in the 4k restoration, wandering about like a cold sun on a sky of tepid, throwaway audiovisual samples. Eustache’s film, with an amplitude that is simply improbable nowadays, no longer belongs to a world like ours, and hasn’t belonged to it in ages; while at the same time it’s impossible not to see a rigorous contemporary filmmaker within it, one who throws uncomfortable truths to our faces under the shape of broad conclusions: the ending had only just begun.

It’s hard to speak about La Maman et la Putain while avoiding the eulogic atmosphere of things that have been lost in the meantime. It’s all the more difficult, given the fact that the film, an uncompromising gaze at “our” world (the languid bohemians that cite anecdotes of Sacha Guitry and who read Proust in their coffee shops), was already describing a decline, a forceful return of anti-social policies, camouflaged under the seductive avatar of publicity. Yet, it was still possible for Eustache to set his film on mediocre-intellectuals-performing-in-sore-sheets smack in the middle of the Latin Quarter, seated at the tables of Les Deux Magots and Café de Flore (they even discuss “the drunkard” Sartre, a regular client), currently the most touristic pocket of postcard-Paris, invaded by city breakers that cheer on the world’s capitalistic acceleration of and the depopulation of its human depth. Nowadays, films about Paris are forced to run away from Paris, to distort its image.

La Maman et la Putain is a myth. And like any myth, it has its part of truth while also having a fair share of pumped-up mercantilism – and one must surely see something both hopeful and detestable (due to obvious reasons) about the masses of spectators that will now flock to see it. There are bits of genius in it – I’m dying for the sequences shared by Jean-Pierre Léaud and Jacques Renard, with their wholly immoral voluptuousness, which puts things into motion through small, sarcastic machinations that are inconsequential, aware of the fact that all is in vain – and there’s bits that lie at the limits, such as Veronika’s (Françoise Lebrun) final monologue: in its overt megalomania, I feel that it announces a wave of “grand moments” in cinema that are grand only to the extent that, through them, their creator can flex their artistic muscles. Eustache is ahead of his time here, too: preceding so many bothersome units of mannerism, the teary face of this woman who describes, while facing the camera, her sexual appetite as a body that abandons itself to the will of the males is still one of the strongest sequences in all the history of cinema – the kind of epiphany that persists when all else is forgotten. The film’s sickly fiber, capable of going deep within the recesses of excess, is what saves it from the process of mummification.

The sculptural beauty of the faces, coupled with this almost viscous length of the shots – cvazi-Tarkovskian strikes of the chisel – is all the more foreboding, given the fact that it doesn’t “open up” towards any savior perspective culled from self-help books. What’s radical is exactly this feeling that things are not right – that something majorly backfired at one point –, but the cause is unclear, a diffuse symptom in the atmosphere of passing time. Alexandre is an unscrupulous bastard, his women are chronically unhappy, and this sweet inferno that retains none of the recognizable marks of hell is, in itself, inescapable. Everything is possible within the world’s neoliberal world, and everything is sad. Escape is a perpetual thought that is impossible to put into practice. Just like its protagonists, La Maman et la Putain has no illusions left. The first have gotten old – poor Léaud, the great old Léaud, attending the premiere, stiff like a wax figurine while the audience thunderously applauds him –, the latter has never gotten bored of looking back at us.

Title

The Mother and the Whore

Director/ Screenwriter

Jean Eustache

Actors

Jean-Pierre Léaud, Françoise Lebrun, Bernadette Lafont

Film critic and journalist; writes regularly for Dilema Veche and Scena9. Doing a MA film theory programme in Paris.