Echoes of the recent past: on “Maidan” and “Close Relations”

All across the post-war years, non-fictional cinema proved, time and time again, that it was not only useful towards capturing the immanent semblance of the countless sociopolitical events that marred the past eight decades, but also its role as a means to understand the present through the lens of the past – a role all the more vital when major contemporary events are highly traumatic and complex. Yesterday, the war in Ukraine entered its second month – a dark milestone, that seems just as unreal as the 24th of February felt, signifying the short time frame in which tens of millions of lives have been irrevocably altered. Now that a new phase of the conflict seems to loom – that of a stalemate, as the advance of the Russian invasion has been fiercely fought off by the Ukrainian resistance –, one that might be even bloodier, it’s paramount fur us to understand what has happened in Ukraine since 2013, until we once more accommodate, for the second time in the last couple of years, to a horrific “new normal”. Maidan (dir. Sergei Loznitsa) and Close Relations (dir. Vitaly Mansky), two films screening in the „DAFilms for Ukraine”, are of the kind that is capable to give pertinent answers to the question of how we arrived here. In a certain sense, both of the filmmakers behind these works are controversial right now: born in Soviet Ukraine, Mansky became a Russian citizen after the fall of the USSR, and is, as such, implicitly affected by the blanket bans of Russian films that various festivals and cinematic forums have implemented in the past weeks; and Loznitsa has just been expelled from the Ukrainian Film Academy by opposing said blanket bans, a scandal which my colleague Victor Morozov discussed in-depth in his editorial on the images of the war. This gives me an even more compelling argument to discuss these films.

Maidan (dir. Sergei Loznitsa, 2014, Cannes Special)

Maidan – meaning Town Square in Ukrainian – had a very enthusiastic reception upon its world premiere at Cannes, less than three months after pro-Russian president Viktor Yanukovych fled the country, two after the annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation, and one after the start of the war in Donbas. Now, almost exactly eight years after the events portrayed in the film, named after the eponymous wave of protests that swept Ukraine from late 2013 to early 2014, it becomes more than just a simple document – it’s equally a prediction of the current times, whose echoes are, at times, bone-chilling. The documentary opens on the image of a mass of protestors chanting Ukraine’s national anthem, followed by „Slava Ukraini! Heroiam slava!” [Glory to Ukraine! Glory to the heroes!] – an anthem and slogan that have now turned into anti-war rallying cries across the globe. A couple of months that Loznitsa captures grow in intensity, anger, and, lastly, in violence – from a peaceful movement familiar to those of us that were protesting at the same time in Romania, against the mining project that would have destroyed Roșia Montană, or against then-Prime Minister Victor Ponta, it turns into one that is marred by bloodshed and destruction, bringing to mind another famous protest square from the early 2010s – Istanbul’s Taksim Square.

The film arrives just as its director was seemingly reinventing his career – releasing two fiction features, My Joy (2008) and In the Fog (2012) after a lengthy run of documentaries, mostly found footage films, of which I would highlight Blockade (2006) in particular, a medium-length film on the Siege of Leningrad during World War II. This time, Loznitsa’s gaze is quite literally in the midst of the events, acting as one of the film’s three camera operators (together with Serhii Stetsenko and Mykhailo Yelchev) and, armed with the training of these previous forays, it knows how to masterfully glide between the protest’s central and marginal events. On the one hand, we have the stage that was raised in the middle of the square, where an entire diorama of society – ranging from activists and politicians to Orthodox priests and traditional choirs – passes through. On the other, we have the smaller movements – volunteers handing out hot teas to the protesters, people warming themselves up with make-shift fires, or raising rice-paper lanterns, all the way to those who occupied public buildings to turn them into makeshift aid centers, and then to those ripping out pieces of the pavement to arm themselves against the police. Of course, in classical Loznitsa style – a master when it comes to reconstructing the soundtrack of the masses –, Maidan has a polyphonic soundscape, which reaches beyond the borders of what is visible in the footage, already the source of strong noises – explosions, blasts –, to which he adds the protest’s various voices: if in the first part, we can eavesdrop on the protesters’ small chats and songs, at its culminating point, we hear desperate pleas for a ceasefire and calls for medics coming in from the stage.

Few explanations are given for what we are witnessing – there are a handful of intertitles, the first of which appears 21 minutes in, that explain a couple of the ongoing developments: Yanukovych’s refusal to sign Ukraine up for the EU membership process, the introduction of new repressive laws, and so on – and so, we are firmly in the territory of observational cinema, priding on long, static shots. That is, until the one-hour mark is hit when, all of a sudden, the imperturbable camera suddenly jolts, then records the flight of its operator: the state’s counter-offensive has just begun, and coughing journalists are trying to escape the fumes of the teargas grenades. The portrait is a collective one, there are no central characters here – a choice which Loznitsa claims was the best way to represent a revolt that had no clear figureheads, a revolt of the (heterogeneous) masses.

But the rhetoric that we witness on the ground already contains the seeds of what we have heard at a global level in the past weeks: already, we hear the first Muscovite manipulations of Nazism (“The president of Russia says that the Maidan is a pogrom!”, we hear from the stage) and the first warlike expressions (“We must liberate Ukraine!”, “If necessary, we will all wear helmets and defend our Ukraine!”, “Let those [gendarmes] who surrendered pass!”, “You have forgotten your humanity!”). It’s not just the arguments bearing the sensation of war, but also the actions themselves, and, as such, their resulting images: we witness burning buildings and barricades fortified with tires and sandbags. It’s outright uncanny at times: the volunteers preparing meals for protesters are wearing sanitary facemasks, their storage rooms packed with imperishable food; at one point, we hear a plea for calm coming from boxing world champion Vitaly Klitschko; at one point, women are called to urgently evacuate, after the start of the violent repression; at one point, we see a graffiti bearing the words “Free Ukraine!”, at one point, we hear that someone is unable to find their brother; at one point, Molotov cocktails start to fly. By the time Maidan is over, one feels the overwhelming sensation that they have witnessed a micro-version of the war that is now engulfing the entire country; its final image, of an altar of flowers and candles raised in the memory of the dozens of people that have lost their lives, now comes across as a sinister premonition.

Close Relations (r. Vitaly Mansky, 2016, in competition – Karlovy Vary IFF’s documentary film competition)

If Maidan offered an immanent, yet simultaneously distant gaze on the turmoil in Ukraine, fixated on a particular historical event unfurling in front of the camera, Close Relations (or, in its original, Rodnye – Relatives) is the opposite, in a certain sense. This family journal directed by master documentarian Vitaly Mansky offers both a multi-faceted perspective of what transpired in 2014 Ukraine, while echoing both small and capital-h History, as they intersect one another with the sort of frenzy that is only possible in lands that lie at the borders of multiple empires – an, of course, like in any film born in the family, it’s a highly intimate perspective. An intimacy that reveals itself mostly in the houses of Mansky’s extended family, where he successively interviews his relatives from around the country. Far from Maidan’s fly-on-the-wall perspective, one that Mansky himself had masterfully wielded previously, in Pipeline (2013) and Under the Sun (2015), Close Relations is operating with full awareness of the inherent subjectivity of any such endeavor: the director is more than a simple interviewer, he is both a narrator and, in some scenes, a character.

„I never thought that I’d be making this film”: by super-imposing these words over the image of a typical communist-era block of flats, Mansky begins his chronicle, spread between May 2014 and 2015, across all cardinal (and central) points of Ukraine, from the west, in Lviv, to the east, in Donetsk, from the north, in Kyiv, to the south, in Odesa and Sevastopol; closing with Moscow, the town that the filmmaker used to call home, but is now about to leave behind, as he decides to live in exile. A particularly striking element in Close Relations had so to do with how regional geographic lines trace not just the lines across which so many families are split (especially ones in the East, still manifesting the effects of the old repartition politics of the communist era), families that oftentimes have complex multi-ethnic backgrounds (in this case, one with Polish, Lithuanian, and Russian lineage), they also trace a deep ideological divide.

This is not a home movie: Mansky’s family is as divided as it is spread out through the land, in terms of both politics and lifestyles. The ones residing in Lviv are, quite naturally, horrified by the war: “Why should people from Western Ukraine die because they decided to shoot each other in Donbas?”, the director’s mother wonders; an aunt that was a one-time fervent pro-Russian supporter reveals that she has just thrown her Nikita Mikhalkov poster in the (recycling!) bin; another is petrified because her nephew is about to be drafted into the army. The ones in Odessa are living the high life – the patriarch is the boss of a local firm that cashes in on public construction contracts –, claiming that the war’s going to be over in the blink of an eye, anticipating the hefty checks of the East’s reconstruction. But the aunt in Sevastopol, a supporter of the annexation, has almost been cut off from the rest of the family (“What do they want from us [Crimean Russians], that we kneel and beg for forgiveness, and to let us back in [in Ukraine]?”), and the grandpa living in a modest home in Donetsk, despite his son’s immense fortunes, is a stalwart supporter of the Russian army.

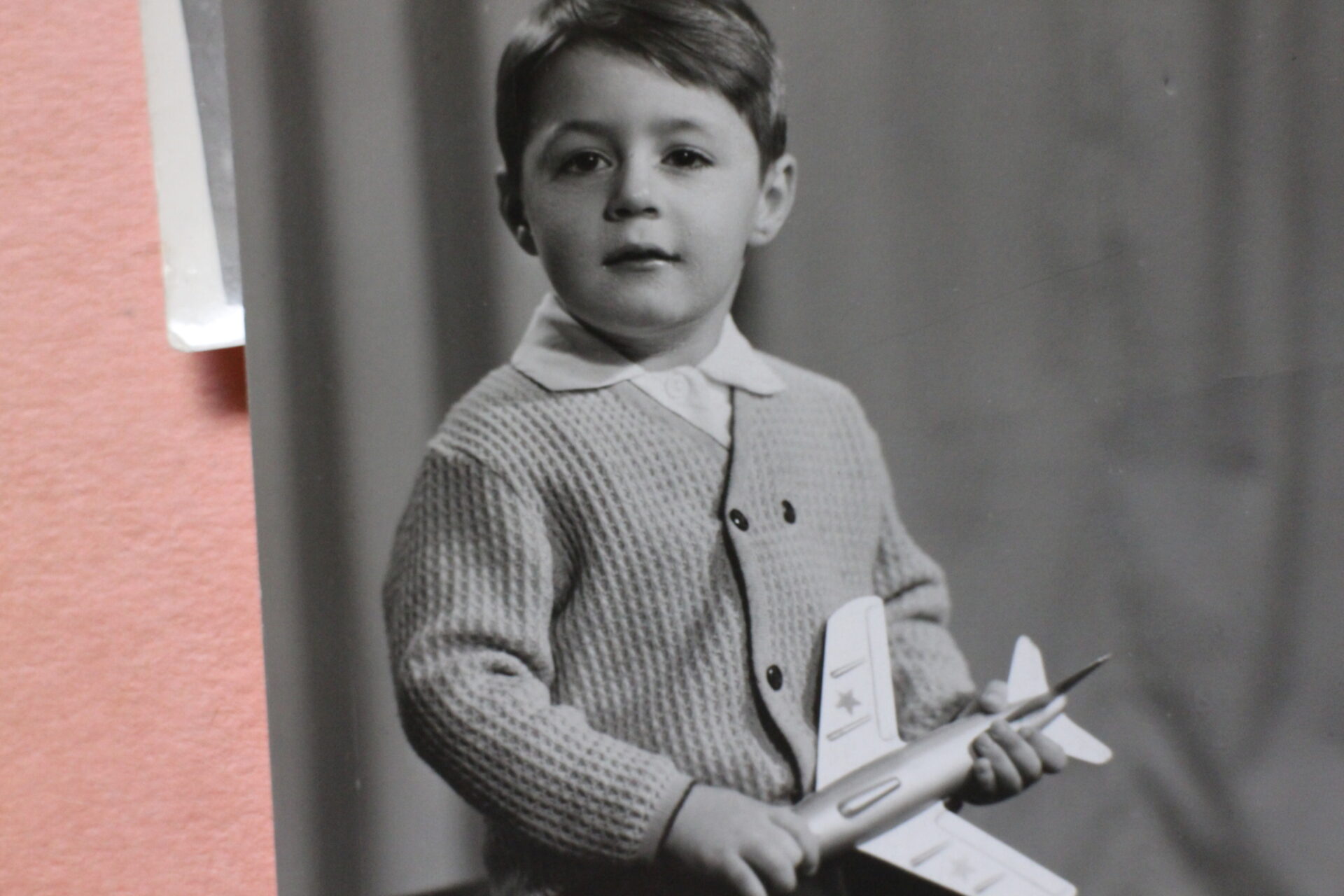

Director of photography Alexandra Ivanova, who’d previously manned the camera for Mansky’s two previous films, points her lens from time to time at the streets of Ukraine, capturing both its architectural variety (from the Austro-Hungarian style of the West, through the Soviet brutalism of the center and down to the impoverished East) and various public moments – how frightful these images of occupied Donetsk seem, strikingly similar to the images that flow nowadays out of Kherson. But Close Relations is mostly a film of interiors. In each of the many apartments that we step in together with the filmmaker, the camera, bearing a slight vignette effect that reminds of old film slides, methodically sweeps across the same few corners – the display cabinets bearing old black-and-white family photos, the television rooms, the kitchens. These recurrent shots of domestic images have several aims: first, and most obviously, it shows how the border between the West and the East is reinforced on television (in a scene set in the flat of Mansky’s cousin in Sevastopol, we witness his family watching two consecutive New Year’s shows: the Russian one, and then the Ukrainian one, one hour later), thus influencing the rifts within the family. On the other hand, the photos are akin to testaments of a family unity that has now irredeemably broken down, a souvenir of times when their faces bore no shadows of fear, nor of pain.

Maybe the word that best encapsulates the sensation of this film is “anthological”: mostly constructed from the various conversations, either between the filmmaker and his relatives or between the members of the family, Close Relations is abundant not only in its multitude of perspectives but also in completely memorable lines, showcasing Eastern Europe’s typical dark humor. “What kind of soldier do you want him to be! All he does is sit all day at the computer!”, says the great-grandma whose nephew is waiting to be drafted; at another point, we find out that another granny passed away while clutching her portrait of Stalin. But even in the most light-hearted of discussions, we can feel the specter of the war, which now shines a light on just how much the West was ignorant of Ukraine’s inner turmoil across the last eight years. We discover many of the main themes and preoccupations of the current war – in the streets and on the television, we can already notice the famous graphical rendering of Putin sporting the haircut and mustache of another infamous dictator, which has become viral in past weeks; we also hear discussions about the Ukrainian far-right, inspired by extremist paramilitary leader Stephan Bandera, waged along the same lines – from complete denial to total over-estimation -; we also see some of the same figures (Zelensky – still an actor at the time – briefly appears on one of the TV sets); we also witness people drawing the same kind dreary conclusions.

Two women who have taken refuge from the Donbas, now living with the filmmaker’s family, claim that they’re feeling stigmatized because of their origins; we hear a cousin, who is working as a nail technician, says that all she ever talks about with her clients nowadays is “the war, the ones going there, this and that, and that we wish that Putin croaks”, but that some Carpathian wizards claim that the war will be over by April; we hear of prisoner exchanges, of common graves, of dead young men, of the fact that it’s the hardest year since 1945, of the fact that it’s all the Americans’ fault, of the fact that NATO is the evilest organization on earth. “We knew who died during Maidan, but now, during the war, everyone is just a statistic”, says another cousin from Lviv, as she’s gazing at a military funeral pass by through the windowpane of a café – unaware of the fact that, just a few years later, many, way too many zeroes will be added to those numbers.

Film critic & journalist. Collaborates with local and international outlets, programs a short film festival - BIEFF, does occasional moderating gigs and is working on a PhD thesis about home movies. At Films in Frame, she writes the monthly editorial - The State of Cinema and is the magazine's main festival reporter.