The Short Path to Forgetfulness: Four films by Paul Călinescu

Between March 29 and April 25, 12 documentaries directed by Paul Călinescu between 1934-1948 are available online for free, on the platform of the Sahia Vintage Cineclub.

It’s important to create archives, but it’s all for naught if you don’t open their seals.

For some time now, some individuals have been stealing crumbs off the tables of Romania’s few film archives. They stuff in whatever fits in their pockets, run off with them to the streets, giving demonstrations on how to eat them – and that is, enthusiastically – and then serve us some. It’s a mighty mission, to return cinema to the hands of film history.

Well, after returning (to varying degrees), the works of the Segalls, Márta Mészáros, Petre Sirin, Slavomir Popovici, and Florina Holban, amongst many others, One World Romania is back, this time with Paul Calinescu, a filmmaker who was part of the trade for about fifty years. In fact, Calinescu started making films before the local trade even existed in the proper sense, at a time when amateur filmmaking was a chic hobby for the rich (“In contrast to other cine-amateurs, whose sole preoccupation was to shoot scenes from their families, we were trying… to make short, topical films”[1], while the professional branch was created with the primary support of the petty bourgeoisie. This brand of patronage couldn’t deliver in the long-term, and Calinescu was a visionary when, using his job at the Ministry of Finance, he proposed that the state should get involved in the production of cinema. That is what led to the founding of the National Office of Cinematography in 1936, a precursor of the modern Romanian Film Center (CNC), an organism which was successively assimilated and then disassociated with various other National Services and Directorates, under various names, up until it ended up as an independent institution. Calinescu was aiming at institutions, to whom he tried to sell cinema as a tool for advertising, a trick he had learned back from the time when he was selling his amateur films (for example, the Ministry of Industry had bought his short, The Industrial Fair of 1934.) A handful of the films which OWR is offering are advertisements, others are informative propaganda films that were commissioned by the legionary regime, and then by the communist one. Of course, Paul Calinescu’s place in film history is, first and foremost, that of the filmmaker that directed the first fiction film to be created during the communist regime (The Song of the Valley / Răsună valea, 1949); but he was proving himself to be a pioneer ever since he was working as a documentarian. In the vein of the fascist friendship that Romania was entertaining with the Axis, two of his documentaries were presented and even awarded at the Venice Film Festival, the very first prestigious awards to be brought home by Romanian cinema – The Country of the Motzi / Ţara moţilor in 1939 and Romania in The Fight Against Bolshevism / România în lupta contra bolşevismului in 1941.

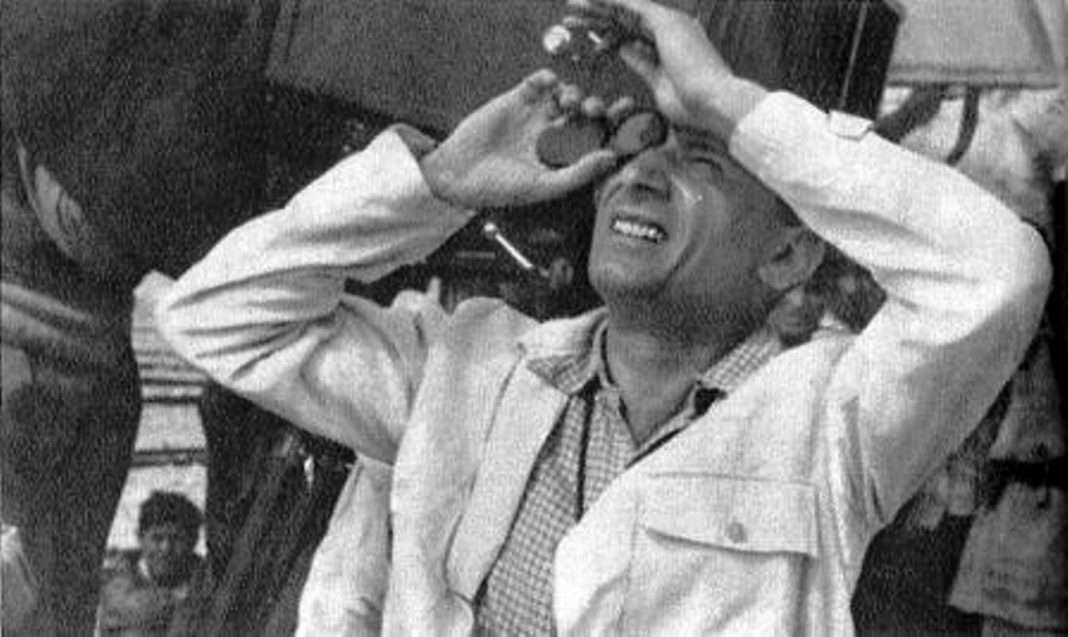

But let us not hastily go for the awards, since OWR’s selection also has one of Calinescu’s early films, the aforementioned The Industrial Fair of 1934 / Expoziția industrială 1934. Set on shooting show-stopping advertisements for cars, cigarettes, locomotives, glassware and, well, whatever the industry men had to offer, the filmmaker’s eyes wander at times at the visitors’ arrogant strutting, at coffee shops and zeppelins, a chance which he takes to wonder in amazement at the view – what a light show!, look, a swan!, what a good-looking woman!. How much enthusiasm does one need to muster the courage of climbing into a hot air balloon, not to mention a roller coaster, with your little treasure of a 9,5 mm camera?

It’s a kind of fervor that withered up until 1940, when Calinescu started to make, this time with an aplomb that was much more formal in nature, an advertisement for the Malaxa Factories. This time around, the need to persuade is tangible, as the images are assaulted by the rocky language of the omniscient publicity voice-over – “faultless”, “fine”, “distinguished”, “vast”, and so on. Haig Acterian, the writer behind the commentary, is not the one to blame; after all, nobody is capable of breathing with a plastic bag around their heads. But one can take a drag of smoke and like it, something that Calinescu indulges in from time to time. How his camera crosses over the molten iron, electrified like a lightning bolt, over the workers’ machinery, just as the pile of cylindrical rockets (bombs?) it shoots seem a dark creature with hundreds of eyes – all of which cannot come from any other place than a marked constructivist sensibility, even if it appears diluted by formalities (alas, formalism versus formalities).

With an even clearer formal aplomb comes Bucharest / București (1940), the selection’s main attraction. And what else could it be – with its modern and cosmopolitan interbellum Bucharest, lying at the intersection of the fleeting kisses between old-age cars and horse-drawn carriages, which continues to irradiate our 21st-century gazes, like a tiny piece of uranium on the footpath of history. And even if we are told that every single photogram is a demonstration of wilderness and that this sumptuous image of Bucharest only stretches for a few measly square kilometers, only for it to give way to grinding poverty, it would still be difficult not to stare in awe at the city of contrasts. Because this is a fabulous document, an album of summertime postcards, but also a documentary at the same time – an introductory shot from the interior of a building, whose windows are turned towards the city center, which almost seems to burst from the imposing architecture that is to be seen outside, says everything. All the more so that the new ’40s-era Bucharest, which was in the process of eradicating the traces of its past (hence its contrast), is the same Bucharest that we behold nowadays, which is also on the brink of eradication; its buildings are collapsing, its parks stunted, its alleyways fattened up by parked cars. However, something seems to remain untouched – the pornographic image of the unruly poverty which is ejected from within the walls of the city.

The capacity of filmmakers such as Calinescu and Ion Cantacuzino[2] to continue their work during communism after being active during the legionary era is something that still lies beyond my grasp. But what I’m sure of is that the relative obscurity of Calinescu’s two Venice award-winning documentaries, which can be extended to the entirety of legionary propaganda films, is mostly because they were stashed away from the public eye, most probably in 1946. Pages from Our Holy War / Pagini din războiul nostru sfânt (1942) is a spectacular arrangement of images shot by Romanian and German camera operators during various fights against the Bolsheviks. Which, after all, is nothing new, since that was the standard type of propaganda film during the Second World War. But Calinescu spends time grooming his film, weaving it after the pattern of spectacular films, even that of fiction. The edges of a rough found footage film are rounded up – a soldier hidden in a trench fires a shot into nothingness, and immediately afterward, in a different shot, we see the sparks of a gunshot; similarly, a handful of wounded soldiers are seen walking onto the balcony of a hospital, a chance which Calinescu takes to follow up with a shot of a snowy path, the same which the soldiers hope to trek across again soon, returning to defend their homeland. The fact that these cuts were stowed away was a great loss. These films don’t bite if you know how to properly domesticate them, not now, not then – by firmly making light of their context.

I remember the words of Jonas Mekas, who once said that everything should be kept. It’s a tricky task, for sure. But we are capable of taming them – everything that has been kept must also be shown.

[1] From „Screenings in time” / „Proiecții în timp”, Calinescu’s memoir, published by the Sports and Tourism Publishing House in 1982, p. 19.

[2] Film critic, as well as director of the found-footage documentary Our Holy War / Războiul nostru sfânt (1942).

Film curator, writer and editor, member of the selection committees of BIEFF and Woche der Kritik, FIPRESCI member and alumnus of the film criticism workshops organized by the Sarajevo, Warsaw and Locarno film festivals. Teaches a course on film criticism and analysis at UNATC. He has curated programs for Cinemateca Română, Short Waves, V-F-X Ljubljana, Trieste Film Festival, as well as the Bucharest retrospective of Il Cinema Ritrovato on Tour in 2024 and 2025.