Charles Tesson, film critic: “What I like about a film is feeling the necessity that brought it into being”

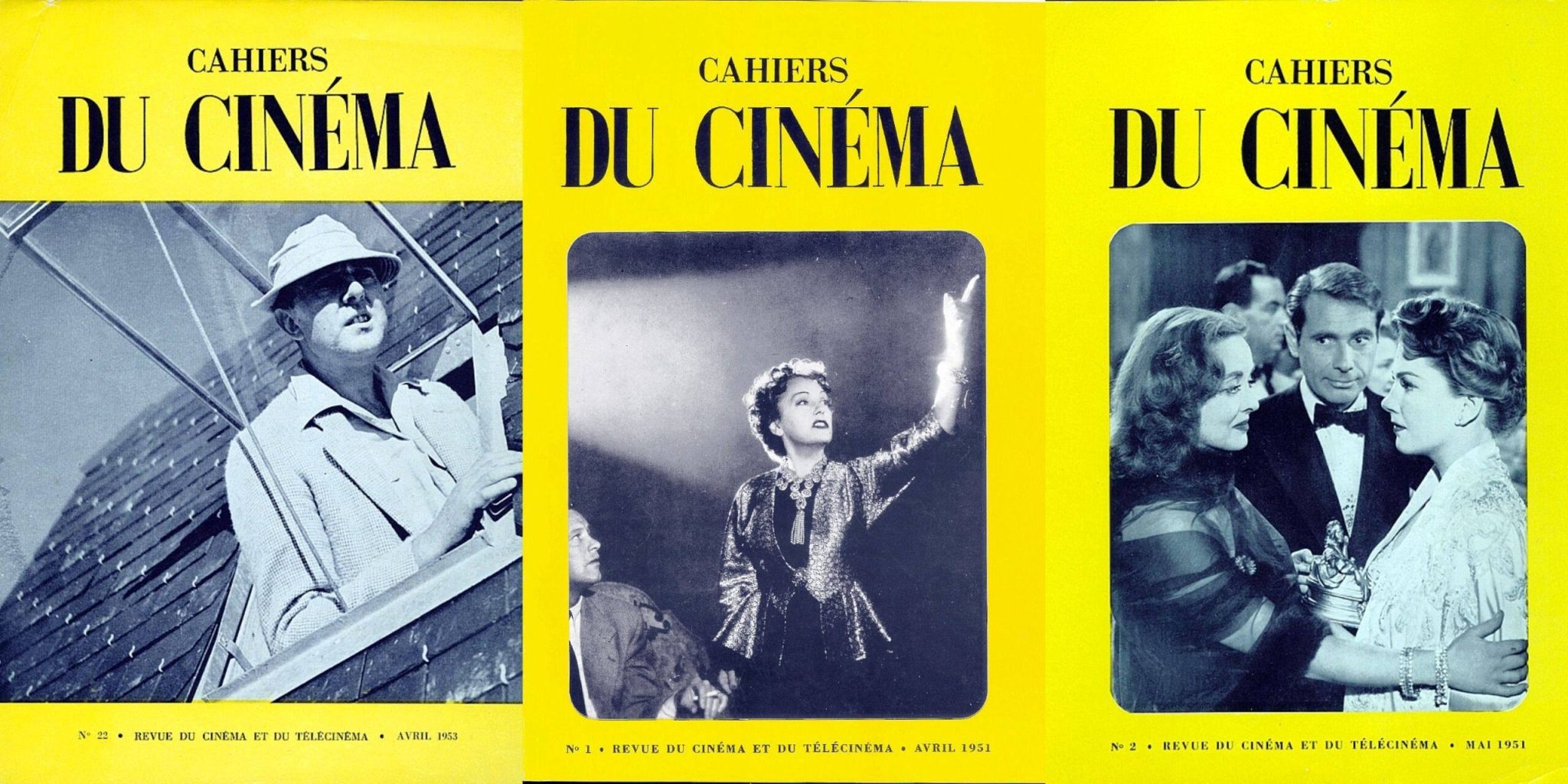

In the world of debates about cinema and the moving image, Charles Tesson (b. 1954) is a landmark figure. He is part of the ’80s generation, those film critics who thrived under the tutelage of Serge Daney and who have taken us, until the emergence of TikTok, on a journey into an increasingly complex audiovisual world. He started, of course, at the influential French film magazine “Cahiers du cinéma”, where he served as its editor from 1998 to 2003. There he cultivated his interest in remote cinemas and sports telecasts. From 2012 to 2021, he was the artistic director of Critic’s Week at the Cannes Film Festival.

About all of this and more, I had the opportunity to talk with Charles Tesson at this year’s edition of the Transilvania International Film Festival, where he was part of the “Romanian Film Days” jury. Needless to say, I was eager to meet in person one of the writers that inspired me early on to become a film critic.

***

I would like to invite you to a conversation about the moving image. A broad topic, closely related to your career, which has taken you through several professional environments. I will start start right away by asking you, why writing about cinema? Where does this desire for cinema come from, which above all, as far as you are concerned, transpires through the act of writing about films?

It is true that we can love cinema and make it a part of our lives without writing about it. That’s the very definition of a cinephile. But writing is probably the point of balance between oneself, the film, and the idea of sharing it with others, those who will read what we write. I have come to realise that being a critic means not only evaluating a film, “criticising” it, but also the desire to pass it on. And then, writing – as many have noted – is an exercise that takes place in a different temporality (either we watch the film, take notes, and write about it immediately, or things come later, etc.): when I started, there were no DVDs, one could only revisit scenes by memory.

Writing is a strange thing because it involves both evoking a film, telling its story (or not), and saying what we think about it – but most importantly, it is this temporality in which I, personally, have felt at home, because it suddenly involved the pleasure of writing. Is it a literary exercise? Certainly to some extent, but not exclusively. It was only by writing that I understood the difference between being a “film critic” and being a “cinema critic”. I mean, we can discuss a film – I believe anyone can do that, talk about a film, evaluate it, and even do something that I’m not particularly fond of, that is, a sort of self-assessment, a checking of one’s own health. But it can also be the other way around, meaning watching a film and letting that experience influence the idea we have on cinema. We grow up with a somewhat absolutist concept of cinema, but ideally, we should reconcile contradictory ideas about cinema. At least that’s how I evolved. Initially, I thought that cinema was only Bresson, Dreyer… I hated Bergman because it was supposed to be Dreyer and not Bergman, the vampire film was Dreyer’s Vampyr and not Murnau’s Nosferatu, things like that…

So you’re right to say that I got to cinema through writing. When I don’t watch films, I feel like something is missing, but when I don’t write about films, it’s even worse. It is simultaneously a personal reflection, an attempt to answer the question, “What is cinema to you?” or “What has cinema made of you?”, and a way of sharing. We can write for ourselves, engage in a personal dialogue with the film, we can write to be read by filmmakers… I, too, read reviews, and when I happen to discover something new in a film thanks to a review, it’s a great joy. To me, being a critic means not wanting to be alone with the films you love.

I’ve always wanted to go where the images come from, as if I were sneaking in behind the screen.

Charles Tesson, film critic

You started writing regularly for Cahiers du cinéma in the 80s, alongside the likes of Olivier Assayas, Alain Bergala, and others. And right from the beginning, we can identify in your work as a critic a desire to shift away from the center of cinephilia (Eurocentric and American cinema) towards the periphery (other continents, other types of images). You have dedicated monographs to names like Akira Kurosawa, Satyajit Ray, and even in the most recent issue of Cahiers, you have an article about 1950s Mexican cinema. It is something that characterises, I would say, a Francophile way of relating to the art of moving images – especially under the influence of Serge Daney – which makes you travel, literally, inside cinema, and beyond it.

There are several things to consider in what you have said. I know many people who are cinephiles, who watch a lot of films, and yet they always remain in Paris or only go to Cannes – and receive the films. I think Daney had this metaphor referring to tennis: they are “on the receiving end”. We can receive a film on a TV screen in our bedroom, write about it, and live through that experience. I, on the other hand, saw things a little differently. I was interested in answering the question, “Where do the images come from?”. Where does a film that talks about Bengal, like Ray’s Pater Panchali, come from? If writing about a film means receiving it and translating it into words, I’ve always wanted to go where the images come from. That is, to travel. As if I were sneaking in behind the screen.

It’s true that Daney influenced me a lot in this regard. And then, I should say that I am part of a generation that was marked by traveling. Cinephilia, as you said, was very Euro-American in the beginning, maybe a bit Japanese starting in the 50s. But there was this very Rohmerian idea that cinema is an art that comes right after Greek and Roman art: Florence was made by Hollywood, not by Europe. I arrived after the ’68 generation, which had a very close relationship with the so-called Third World cinema, connected to the struggle for independence; it was something very political. Suddenly, the relationship became more cinephilic, more curious to discover the places where cinema is made. When I joined Cahiers, I had this baggage of impressive texts by Daney, Oudart, Bonitzer – oh là là! – but I found that I enjoyed being a film journalist. I mean, for example, going to Hong Kong for a month to see how things work there. Between pure criticism and film journalism, there are two very different writing regimes.

For me, the love of cinema began to translate into receiving films and writing about them, but also being a journalist. Going back to tennis, after “receiving”, returning the ball is like writing the text dedicated to the film. But sometimes it’s also important to know who served the ball and how things are going on the other side of the net.

As for the image, like many others, I have inherited the Bazinian concept of “impure cinema”. I’m quite bothered by this phrase, “It is pure cinema”; I avoid people who use it. I find it ridiculous and dangerous, something very absolutist. Wherever an image – any type of image – was at play, I was interested.

“In sports, there is a certain dramaturgy, there is always a script”

You use many metaphors borrowed from the world of sports. You have even taught courses at university about the relationship between sports and TV, sports and cinema. How did you get to this idea of examining the sports image?

I have always been interested in sports. And how sports are depicted in film. Martial arts movies were the best in this sense. Bruce Lee was amazing, without question… In The Matrix, there are special effects, but back in the day, Jackie Chan trained on his own. It was clear that, no matter how cinematic everything was by nature, a very high level of athleticism was required to produce such action. Or how in the middle of the narrative comes a moment of dancing, with Fred Astaire, for example, and suddenly everything is dazzling.

I always wondered about several things: first of all, what is the body capable of? And then, how can cinema reproduce that properly?

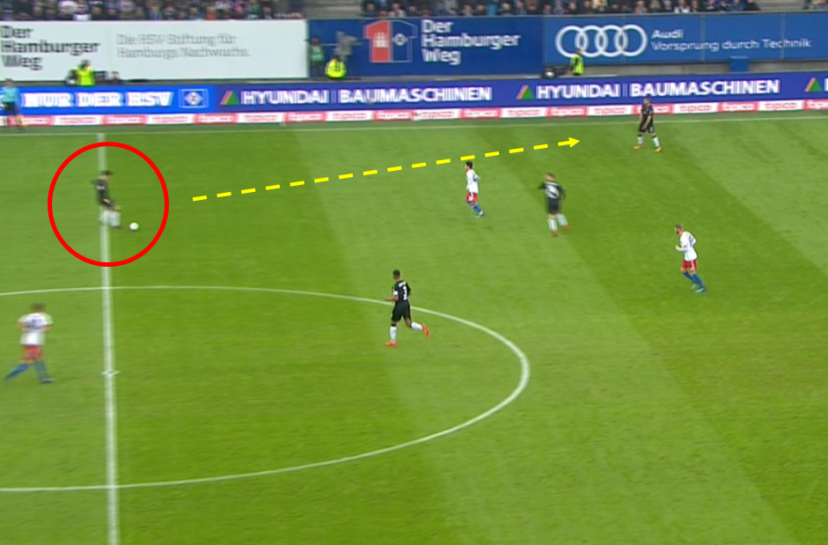

In the 80s, I used to go to the stadium to watch football matches, and then I would (re)watch them on TV. People took televised broadcasts as a genuine replay of reality. Sure, I also believe that the image can serve as proof, or as a “true record”, as we used to call it – but it was necessary to say: no, there is editing, montage, different angles and shots… It’s not as it really is, it’s an interpretation, a perception. For example, when there is a foul, there is always the one who committed the foul and the one who was the victim, you can edit the footage to present the events in a certain way. Plus the idea that in every sport there are staging issues that need to be resolved, whether related to the technical plan or the dramaturgical intent.

It’s interesting that all these debates were long present in Cahiers, which in its early days was called Revue du cinéma et du télécinéma before the television part was gradually abandoned. And then, when you started, television began to regain the attention of critics.

Yes, there is a Cahiers anthology called Le Goût de la télévision (i.e. A Taste of Television) where you can find articles from the 50s about TV shows, political debates, etc. Even Bazin wrote a lot about television, about literary programs. I think that was one of Cahiers‘ distinctive features, compared to other magazines that only discuss cinema and nothing else. But it is also about the things that cinema – which emerged after painting, literature, photography – owes to other arts, as well as the moment when it begins to inspire and nourish other fields. Live broadcasting began with the Tour de France. In fact, most technical inventions – lighter cameras, helicopter shots, etc. – found their place in cinema after appearing in other areas.

I have always been against conflicting positions between audiovisual sectors, and always in favor of porosity. I was a reader of Cahiers when the famous round table took place during the 1978 World Cup in Argentina, in the midst of dictatorship [where the main editors of the magazine, Serge Daney, Serge Toubiana, Pascal Bonitzer, together with other experts, like Jean Hatzfeld from Libération, thoroughly dissected the mise-en-scene of the matches seen on TV] – so these things already existed. But it’s true that I was always allowed, even encouraged, to write about topics outside the sphere of cinema.

That’s what I wanted to ask you. So you didn’t see this break out of the “cinematic paradigm” as a transgression of certain dictates…

Not at all. Not at all. That’s what’s so great. On the contrary, in six, eight, ten-page texts, this story was part of a wider reflection on the image. And that’s because in sports there is a certain dramaturgy, there is always a script. You see coaches and sports directors writing a script beforehand about how the game is going to play out, and that script can change in very unpredictable ways once the game starts. Plus, there’s the concept of the live broadcast, about which philosopher Paul Virilio has written extensively: the live as “tele-presence”. Not to mention the volume of editing and televisual writing, which is exciting in sports like football, for example. The way live coverage of football matches has evolved in recent decades tells us a lot about the entire universe of moving images. Here, we can see that the way things are filmed is connected to what we expect from the viewer. At one point, the aim was to film the match as a stand-alone show, then the focus was on highlighting the stars, the club’s main players, then we turned the viewer into a referee who judges whether there was a foul or not, and now we are all viewers-potential coaches. We reserve a certain place for the viewer that evolves over time.

Probably the generation you belong to is the first to bring to the fore the idea that cinema, even when it’s not the focus of the discussion, can be the best school for learning how to watch images.

Absolutely. Whether we watch a movie or a sports event – it’s pretty much the same thing. Take the Tour de France, for example: the fact that we can capture the pain on a player’s or competitor’s face during a sporting event is extraordinary, and very cinematic. Suddenly we discover a formidable power in the image. What strikes me the most about today’s cinema is that Bazin’s ideas are less and less adopted. The idea of forbidden editing, the necessity of having the human and the animal in the same frame for us to believe what we see, has been replaced by a green screen where everything is possible. But a remnant of Bazin’s philosophy still persists in sports: the body-physical medium unity.

“Daney had this idea of speaking to a film just like you would speak to a person”

I would like to go back to Serge Daney for a minute, since you knew him closely. In the Trafic (i.e. Trafic: Revue de cinéma) issue dedicated to him, you wrote a beautiful piece about his relationship with sports. Could you please briefly evoke this unique figure who opened many, many paths?

I first met him as a reader, when I was still living in Nantes. In the 1970s, there was no official degree in film studies in France, but there were some film courses. And I saw that Daney, Bonitzer, and other people from Cahiers were teaching. So I set out to write a paper on the opening scene of Dreyer’s Vampyr at the University of Paris III, and that’s how I was able to attend Daney’s classes as an auditor. He was very convivial, he would stay to chat after class. And I gave him my paper, and he thought it was good and said right away, “Come and write for Cahiers.” He is the one who brought me to Cahiers and took me under his wing in a way. During that time, he and Serge Toubiana wanted to open the magazine to other writers, and that’s how Toubiana found Assayas at Tolbiac, and then Leos Carax… The university was full of possibilities.

Daney reacted to whatever was happening. I called him an “MDI”, a Monster of Ideas (laughs). Because he had a theory about everything, he was a thinking machine, truly fascinating and quite astonishing. He drew inspiration from everything he encountered. He would notice a small detail and make use of everything presented to him. He wasn’t someone who would say, “I watched a film and I’m talking about this film and nothing else,” not at all. You could sense that everything around him constantly motivated his reflections. You could tell he had built a view of cinema that was enriched by the surrounding reality.

He had this very simple idea of speaking to a film just like you would speak to a person: “Oh, long time no see!”, “How are you?”, “You haven’t changed at all.” He didn’t like to say whether a film was good or not; instead, he would ask questions: “What do you expect from me as a viewer?”, “What are you doing here, in today’s cinema?” For me, this is a fundamental exercise in film criticism. He would often say, “This film doesn’t want anything from me” or “This film wants to be admired,” and he couldn’t stand that at all. He wanted to play with the film, to be surprised by it. As Georges Franju said, “I love films that make me dream, but I hate films that dream for me.” I took this idea from Daney, that a film is an experience in time that establishes its own time.

You have successfully applied the tools learned through film criticism to another branch of the industry, as you were responsible for the selection of the “Semaine de la critique” at the Cannes Film Festival until recently.

It wasn’t necessarily an obvious transition. It should be said that there are different types of critics. There are critics who are remarkable analysts of filmmakers discovered by others. For example, Jean Douchet, who was not a great discoverer of films. When he went to festivals, he was often wrong, and I say that without any reproach. Instead, he was an extraordinary commentator on Fritz Lang, Hitchcock, names discovered by the previous generation. And there are critics who are great forward-thinkers, who bring new names to the table. That was my jam. For example, when I became editor-in-chief of Cahiers, I went to South Korea in 1998 to interview Hong Sang-soo, who was completely unknown in Europe. It’s like in Westerns, where there is always a character who will go to test the ground, and based on what they find there, it is decided whether the expedition continues in that direction or not.

What I like about a film is feeling the necessity that brought it into being: why the director made that film and not something else. The film may even be mediocre, but I have to feel that it needs to express itself through cinema, through framing. There are films that I think could have been a discourse, a manifesto, and it would have been enough.

What I see today in festivals, and I admit it’s a bit snide, I call it the “theory of street lamps”. When dogs want to mark their territory, they urinate on a lamppost. And there are directors who make copycat cinema – they don’t make the film because of the inherent need to make it, but so that the others can say, “He’s one of us, he made the film as we would have made it.” So that they can say, “I belong to camp X.” But of course, in camp X, there are very talented people and less talented people.

What I like about a film is feeling the necessity that brought it into being: why the director made that film and not something else. The film may even be mediocre, but I have to feel that it needs to express itself through cinema, through framing. There are films that I think could have been a discourse, a manifesto, and it would have been enough.

Charles Tesson, film critic

The experience of being an artistic director has given me an exciting perspective on young cinema. It was a challenge. I had to watch almost 400 films a year from at least 60 different countries. But it’s a different position from being a film critic. Sometimes you have to forget the critic within you because you’re not there to please your fellow colleagues or show off how much good taste you have. Rather, you have to think about the life of the film, its potential course. It is the place where you can realise most deeply that cinema is in constant change. But the contact with the young cinemas and the new voices discovered in the “Semaine de la critique” makes me rather optimistic. The need for cinema – for the experience that cinema continues to offer in relation to the world, to time, to life – will always persist.

Film critic and journalist; writes regularly for Dilema Veche and Scena9. Doing a MA film theory programme in Paris.