Jessica Woodworth: “I am inevitably asking myself where we are going”

After directing shorts and documentaries and co-directing several other acclaimed titles such as King of the Belgians (2016), and The Barefoot Emperor (2019), Luka is Jessica’s Woodworth first solo fiction feature. Here is an interview with the director, after being premiered at IFFR’s Big Screen Competition (International Film Festival Rotterdam).

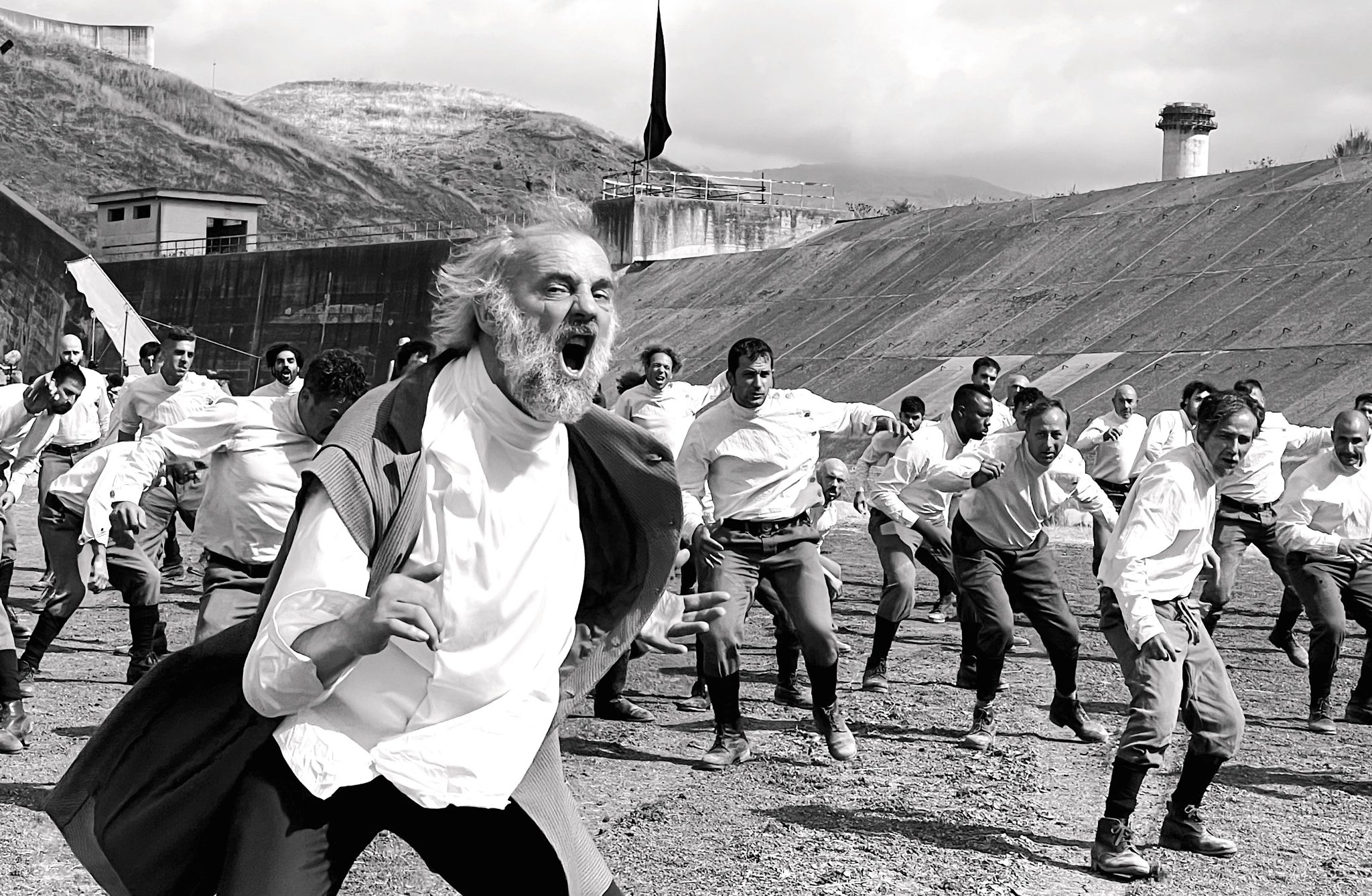

Men trapped in an isolated environment, immersed in propagandistic rhetoric and preparing for a clash with a mystic imaginary enemy beyond the borders of their hierarchic world. That’s how Jessica Woodworth’s atmospheric military parable Luka which just premiered at IFFR’s Big Screen Competition could be briefly described. However, this sentence could as well potentially apply to any anti-utopia that deals with social control and contradictions. „Obedience, endurance, sacrifice“ is the proclaimed motto in the military camp while what we actually observe in the characters’ portraits is emotional individualism and an urge for free expression beyond the shackles of discipline.

After directing shorts and documentaries and co-directing several other acclaimed titles such as King of the Belgians (2016), and The Barefoot Emperor (2019), Luka is Jessica’s first solo fiction feature. She gladly shares for Films in Frame insights around the concept and working process behind this unusual film that resonates startlingly adequate with the current global apocalyptic mood.

Luka is not based on Dino Buzzati’s 1940 novel The Tartar Steppe, it is rather inspired by it. What did you find particularly inspirational?

The based-on and very faithful to the original source version was already done by Valerio Zurlini in 1976, titled The Desert of the Tartars. But I found other dimensions of the book deeply inspiring for being exposed on screen: the mirrored by nature angst, the absurdist humor, and this innate sensuality – the unspoken hunger and desires that inhabit the characters. However, what captivated me most is the arena of the future. I have two daughters and I am inevitably asking myself where we are going. Because of the multiple emergences of our time, the most compelling choice seemed to move the action to the future in a world where a cataclysm such as the lack of water has manifested. Putting it there I wanted to quietly lay on the ground something that would resonate without being addressed literally. When I met an heiress of Buzzati in Italy and told her that I will take this premise, shake it all up and change the names, she asked me about the ending. And I said that the way it is in the book does not interest me at all as the main character there dies. In my loose adaptation, I knew from the very beginning what exactly will happen in the end. Everything was built up towards that moment. The only original line from the book ending that I kept is “We are the north”.

And this line actually brings hope for a possible opposition to the status quo. Luka is determined to be a warrior but the character of Konstantin throws doubt on the heroic side of the plot from the very beginning. Also, you chose very handsome actors for these military roles, they almost look feminine which somewhat undermines heroism. Was it intentional?

I did not aim to make a cynical film, and this is not an endeavour to make a mockery of men. The most important in the building of the ensemble was the order. The first challenge was to find Jonas Smulders for the role of Luka and then from there find the right Geronimo who is sort of a butterfly figure. Geraldine Chaplin was also cast very early into the process but I never looked for a type. I was not concerned at all with accents as well – the film is a coproduction, so I looked for actors in all the participating countries. Beauty is a powerful thing and it’s true that the main actors look very handsome but I was probably more sensitive to their voice timbers. All happened as per intuition.

The film recreates an exclusively male environment with Geraldine Chaplin as the only woman on screen, however in the role of a male general. But females are behind the camera and I think that you and the cinematographer Virginie Surdej somewhat break the typical masculine tension of the military environment. What is your perspective?

War belongs to all of us, males and females throughout time.

While it is predominantly initiated by men…

This is true, absolutely. I have many military men in my family.

Which is probably your personal connection to the story?

I guess so. My father was a nuclear disarmament expert in the Cold War, so I come from an environment where I witnessed men gambling with the fate of nations. I’ve never smelled the battlefield and have never been drawn to wars but I am completely entitled to imagine those worlds without placing the gender border as an issue. I wanted to work with Geraldine because she is beyond gender, just a volcano of talent, intelligence, and experience. I told her I could not make the film without her but she had to play a man and she agreed.

By the way, I did an experiment a few years ago by writing Luka as a female character, just out of curiosity. I populated the plot with a number of female soldiers and named Luka Helena but it turned out a completely different story because it disrupted all the dynamics in the fort. Live-giving bodies simply have different values and power and it was not interesting. So, I returned to the purist concept of these guys hoping for salvation. I also wanted to keep it all very accessible.

However, perhaps namely your female perspective is what made that military film accessible, and conceived this clean environment without burdening the viewer with too specific details. You left behind practicalities and focused on the essence with an emphasis on human interactions.

This effect is also due to the filming locations, these vast landscapes in Sicily and the underground caves around Siracusa. In the process of committing to the spaces, the production design team could not add much, and could not really “dress” them because every element we would try to put was belittled by the scale of things around. I wanted to keep it as simple as possible in order to allow the primary events to take place. The point of interest is actually the landscape of the characters faces.

The black-and-white image also helps create such an uncontaminated environment.

There was never doubt about the black-and-white, as well as the 16mm film stock. We did not need more than the 16 mm can offer. I was looking for sharp contrasts and dense dark but everything beyond that disappears because one cannot grasp the ephemeral. It is part of the story. Also, the lightness of the 16 mm camera helped to accent the dance between the protagonists – the cinematographer was following them, not the other way around, and their choreography was mostly improvised. The instruction was to get into the breathing of the men and follow them. The color in this case would have been deeply distracting.

I was looking for sharp contrasts and dense dark but everything beyond that disappears because one cannot grasp the ephemeral. It is part of the story.

Virginie Surdej’s camera transmits masterfully the tension and angst in the air. Did you work purposefully for achieving this effect or it was a natural result?

We spent a lot of time on the locations and their nature required us to sit and listen. Before we started shooting, we were already charged with the emotion of the place. We did not storyboard a single episode because that would have crippled our process. Sometimes we would hit a wall in the sense that a filmed scene was not really breathing. So, we would clear the set and just walk in circles in order to find the right path. And if we didn’t feel it, we didn’t shoot it.

Luka tackles the subject of propaganda. In this current alarming situation in which the world seems to be threatened by a third world war, how do you think it could be interpreted?

The idea was conceived before the war in Ukraine but yes, the meaning alters in today’s context. The situation, however, did not influence the post-production decisions. It’s tragic that the world can repeat this scenario. Reflecting on the events through the course of a movie helps to dislodge certain conclusions and open up to cross-references. One of the challenges was to keep things away from tropes and simplification.

The idea was conceived before the war in Ukraine but yes, the meaning alters in today’s context. The situation, however, did not influence the post-production decisions. It’s tragic that the world can repeat this scenario.

Mariana Hristova is a Bulgarian film critic, cultural journalist, and programmer, with a special interest in the cinema of the Balkan countries and Eastern Europe as well as avant-garde, amateur, and underrepresented cinema. She is a regular contributor to Cineuropa, Talking Shorts, East European Film Bulletin and Filmsociety.bg, holder of the Balkan film website Altcine.com's film critic award, and member of FIPRESCI. She currently lives in Barcelona, Spain where she programs for various festivals and institutions. She also works as an indexer at FIAF - the International Federation of film archives.