Magda Mihăilescu: “The Critic – neither mummy, nor sentinel”

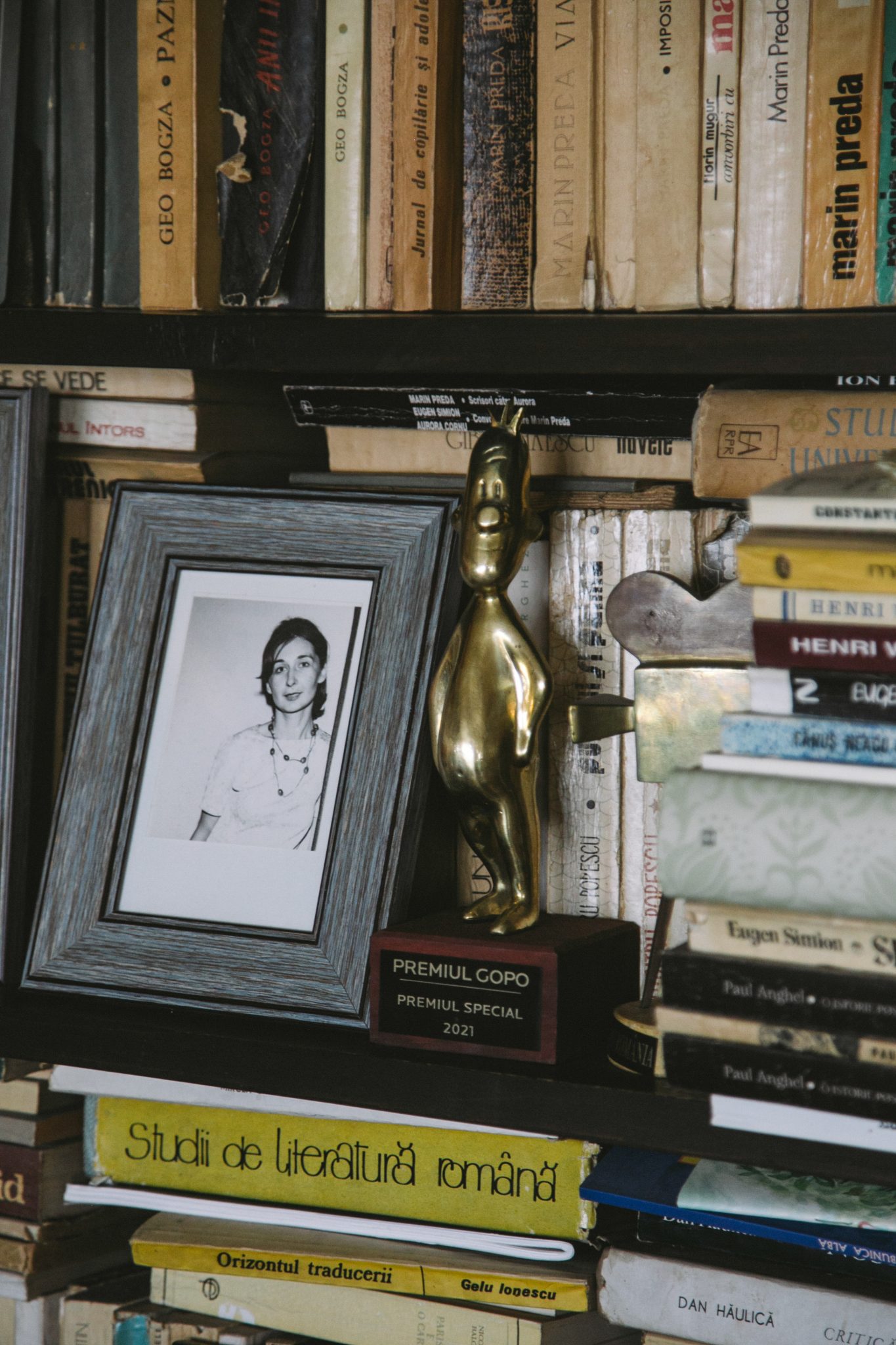

Magda Mihăilescu is one of the most important Romanian film critics, with an activity spanning over five decades. Born on Jun 13th 1937 in Ploiești, she graduated from the Faculty of Journalism (University of Bucharest) in 1960, after which she wrote in the cinema rubric of the Flacăra newspaper (19161-1976) and Informația Bucureștiului (1976-1982), while also collaborating, before the Revolution, with magazines such as Cinema, Contemporanul, România Literară, Luceafărul or Familia. After 1990, for many years she was in charge of the film page of the newspaper Adevărul and the weekly supplement Adevărul Literar și Artistic while collaborating with the magazines Noul Cinema and ProCinema. She contributed to the books The Contemporary Romanian Cinema. 1949-1975 (1976) and Lucian Pintilie. Guardare in faccia il male (2004) and she published Sophia Loren (1969), These Giocondas without a Smile – Conversations with Malvina Urșianu (2006), Truffaut, the Man who Loved Films (2009) and My Sister from Australia. Passed Reminiscences with Irina Petrescu (20019). Alongside Cristina Corciovescu, she coordinated the collective books The Ten Best Romanian Films of All Time (2010) and The New Romanian Cinema. From Comrade Ceaușescu to Mr. Lăzărescu (2011). Over the Years she has been a member of some of the most important juries from festivals across the country and overseas. She has been awarded numerous awards from The Romanian Filmmakers’ Guild and The Film Critics Association, and in 2021, to acknowledge her exceptional career, she was awarded a Special Prize at the Gopo Gala.

You said in a 2009 interview given to the literary critic Mihai Iovănel for the Cultura magazine that you would have liked to study film studies, only that they had just suspended the department so you went on to study journalism. Do you have any regrets from this point of view?

No, none. I am going to quote Serge Daney, a favorite critic, one of the very last great stylists of film criticism, at least in France: “The exercise has been lucrative, gentlemen.” He was referring to critique, I – to college. I have never regretted it. On the contrary, as time goes on, I grow prouder. Even if the there have been some gaps of the aforementioned faculty, the very first institution founded to study journalism at the University of Bucharest, I have had the privilege to have some great professors. I was part of the last of the alumni. Those before us had the chance to study world literature with Tudor Vianu, but we couldn’t complain, as we had Zoe Dumitrescu-Bușulenga, Vera Călin, Edgar Papu. I will never forget the latter’s lessons on Goethe’s Faust.

How could I abandon such an institution? Luckily, at the Students’ Center, which had been newly opened, they organized cinema classes. One of the classes was held by Suchianu, another was held by Ion Barna, who had been ignored for a long time in Romania. He was an excellent film connoisseur and he had such a great capacity for expressivity. I attended these two classes, and for the rest I recuperated. Which, to use one of De Gaulle’s questions, meant ‘a vast program.’

You are referring to cinephilia.

My cinephilia was candid and a bit puzzled. I was a child born at the onset of war. My first memory of a film is that of a scare to death, when I was about four years old, when I still struggled with Romanian and I used the third person to talk. I was just flabbergasted just by looking at the big screen and I started yelling in the cinema: “I want to go at his house!” Not even to this day do I know and, unfortunately, I did not ask my mother what film were we about to watch and why did we enter the cinema room when the Journal had begun. Of course, it had war images. I thought that the plane that was free falling was headed towards me. I was reliving, just like so many other people, the experience of the first spectators unsettled by the film Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat Afterwards, what cinephilia could one talk about during the ’50s, during my preadolescence, when I would only Soviet films? I knew by heart Ballad of Siberia, Six P.M. I also know the songs from the Cossacks of the Kuban film. To my mother’s despair, I used to see each film six-seven times. Of course, I did not know the truth about the films – life in the kolkhoz, socialist races, I was interested only in the mysterious cloth that was set in motion. I was under the impression that behind the screen something, too, was happening.

These were my innocent cinephile beginnings which I lived through on my own and I had not confessed, for I did not have whom to confess to. Until a moment in time. A professor was to initiate me in true cinephilia, Umberto Domenico Ferrari, better known as Umberto D. I did not know how many people have gone through such a moment in which they would feel that a mystical fire surrounds them, that something is happening, that the screen can tell a story differently than a book could. I was coming, just like everyone else my age, from books and I felt this strange feeling that the movie can humble the words. Of course, at twelve I didn’t think like that, this came later, when I reconstituted my past. Why did it shock me professor Umberto’s gesture of taking out his hand, opening the palm to ask for money, but, when seeing a colleague closing in, turning his around, as if he wanted to check if it’s raining or not? That was the moment when I discovered that there is something which, later on, I would come to learn that it is called the cinematographer’s gaze. It was an epiphany of sorts, if you will.

Then, slowly, many other Neorealist or poetic realist movies came in the movie theaters. At the beginning of the ’60s there were embryos of cinematographic education began occurring, embryos that were building a cinematographic culture through nights called ‘Friends of Films’ that had been initiated by the critics Ana Maria Narti and Tudor Caranfil, the nucleus of what would become Cinemateca. Then, very early on, I entered an editing room, at the Flacăra magazine, where I had come across a great luck, for the chief-editor was a former professor, an avid cinephile and connoisseur of film theories, Henri Dona (with whom Magda Mihăilescu was to get married some years later – author’s note). I had the advantage of working in a place where I would the great magazines of foreign cinema, which weren’t available not even at the Cinema magazine: Sight & Sound, Bianco et Nero, Les Cahiers du cinema, of course.

The ’60s were also the period of a great opening of Romania towards the West.

Those had been the years of a great explosion of cinephilia. When I launched my book on Truffaut, I reminded people that our generation, born either at the beginning or during the war, did not enter the life touched by an angel’s wings. But, if I had had any luck, it was that of being 20 during the ’60s. I don’t know how to say this, but it was a sort of divine compensation for us, those who loved cinema. 1960 meant La dolce vita, Aventura, Jules and Jim. The boogeyman of television had not yet scared us. This did not mean that we had filled with one breath all the gaps of our cinematographic culture. It is difficult to recuperate this much. I will give you one single reason. Godard had been seen integrally in Romania only after the ’90s. I felt the gaps when I sometimes couldn’t write, when I knew that something should lead me to a reference, but I did not have it fully. Afterwards, lest you forget, we did not have the advantage of the Internet. We did not have all the dictionaries that one could have during those years. At the same time, I think that this the charm of true cinephilia, to know that you managed to overcome a certain resistance, that you managed to make your own way, that you zigzagged through some potentialities. Cinephilia, the one we inherited via the French, as part of history and culture, presupposed a mysterious path, erased today from the map. Cinephilia has since built other practices, for, purely and simply, others are the ways through which you can hit the mark. This is the evolution of life. We cannot stay stuck with what was.

You began work as a journalist, then, steadily, you became a critic. Do you consider that it is a journey that has more benefits than that when you start from the get-go with critique, essays and hard-to-digest texts?

I am not saying that this path is mandatory or ineluctable, but there are some benefits to be had, because you get impregnated by a certain film atmosphere. It does not answer your questions, but it brings up questions to which you will find the answer later. Then, it induces a certain humbleness. Today, many critics, starting with Andrei Gorzo, show their immense admiration for André Bazin, but I do not know how many of them have his humbleness. The humility of the ‘Saint with the velvet cap,’ as Truffaut had named him. I begin a bit lower than that. In fact, I have always considered myself to be a sort of foot soldier who was working on his small patch of land without waiting for any public reward. At the time we are discussing we did not take into account traveling, and I did not even dream of publishing a book or two. Then, slowly, of course that I had made headway in my relationship with my work. However, I go on to look with a certain uncertainty the straight dive into doctoral studies on Bergman, let’s say, without the respite of bathing into the culture of the place and time. I am giving this example because Bergman has intimidated and unsettled me more than any other creator. I love him, I have been preoccupied with him, but I went to great lengths to find the answer to a fundamental question: why did a Protestant like Bergman and an atheist like Antonioni arrive at the same conclusion, of a mute God? I do admit that I did not get a sufficient understanding of his oeuvre easily enough to be sure that I could write a book without fumbling it too bad. Maybe school gives young critics the certainty of being on high horses, but I have my doubts regarding school as an institution nowadays in our country. I think that you also need a bit of apprenticeship in terms of theoretical preparedness too, for, otherwise, there is the risk of gliding through quotes, a certain chasing after references which, I don’t know how but, seem to always be the same ones.

As a journalist and film critic from the ’60-’70s, you had the privilege of watching many movies, of which some did not make their way to the public. Did you feel frustrated by the fact that you could not write about them and could not recommend them to the public?

Of course, it was frustrating. Our profession gave us this advantage that others did not have. There were There were these famous watch sessions on Monday evening at the Studio Cinema, of the Filmmakers’ Association, as they were called then, where, indeed, we could see films others only heard of and they would never dream of seeing. Back then we did not have the video cassette circuits. Of course, it was frustrating not to be able to write, but, at the same time, the joy of being able to watch films was greater. And there is something else: we somehow had gotten used to our lives, as sad as they were. We knew what world we were living in. Atop all the other sad things of our and other generations, the fact that I was not able to express my extraordinary ideas about a Visconti film was not the biggest drama. There were other things that were much more humiliating.

I assume that at Flacăra ideological control was not as strict as compared to Bucharest Information, where you ulteriorly ended up. How did censorship work in the case of cinema magazines and how did you perceive it?

At Flacăra I was brought by my professor from faculty, the head of Journalism Studies, Henri Dona, whom I mentioned before. I had learned also learned from him a strategy for choosing titles, so that some texts might go uncensored. It was what I would call the strategy of neuter names. Of course, this would go on until scandals about one film or another would erupt, as it happened with A Film with a Charming Girl, when all the chronicles had been taken out at the last minute. After Henri Dona, our chief-editor was Adrian Păunescu, whom I worked with a few years. He’d let me be, so I could write about anything I wanted. There was one thing he couldn’t understand: why see a film six-seven times? When I told him that I had seen Ash and Diamond 11 times, he told me that this was pure madness and had me see a doctor. I left Flacăra I started disagreeing with the proportions the Literary Circle had gained. There were some frictions. Dorin Tudoran and I were responsible for the Circle’s chronicles, the very first edition, when they held it in small spaces, in an amphitheater, a cinema room. The moment it moved onto stadiums, Dorin Tudoran whispered to me that it was time to withdraw. There was no need for that. Păunescu had informed me that we could not collaborate anymore. I must be honest, I can’t say that he fired me, he made the transfer to Bucharest Information possible. This was the end of the first part of my career, in which, one way or another, I had been protected by chief-editors who understood my passion for film. Bucharest Information was then led by an activist. A nice person, but unsettled by the fact that I would laud excessively the great Soviet films of the era, such as Konchalovsky’s Siberiade. The review for Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears gave him a hard time. After the film won the Oscar, he calmed down. Then came the period when I was taken out of the press.

When and how did it happen?

In 1982, when my husband’s daughter left, legally, for Israel, to her mother’s grandparents, mother whom she had lost during childhood. I did not announce the event, I felt I had no reason to, given that it was a family matter. Then I was sent to work as an editor at the Cinematographic Factory of Bucharest Municipality. I did not write, but at least I got to watch films. That’s where December ’89 found me.

During the time you worked for Flacăra and then for Bucharest Information, and also during the ’80s, the most emblematic cinema magazine was Cinema where you also collaborated every now and then. Did you not envy those working there?

No, I knew that I was never going to work at the Cinema magazine. It’s more complicated to say why. During the years I had worked for Flacăra, and Bucharest Information respectively, I was the sole writer, the most favorable situation for a critic who wanted to put in work. When they took me out of the press and sent me, as I said, as an editor at the Cinema Factory, in ’82, someone tried talking with the head of the Cinema magazine from back then. It wasn’t a political institution’s magazine, as was the case with Bucharest Information, which was a newspaper of the Municipal Party Committee, so the rigors regarding one’s dossier were different. They’d overlook things sometimes. The answer was categorically no.

But would you have liked to be part of the editorial team?

Most likely, although I was used with the work routine of a weekly paper or a daily one, which were better suited to my character.

You spoke on several occasions about the moment when you met Federico Fellini in Italy, but I would like you to tell it one more time.

I managed very hardly to arrive to Italy. If not for the booklet I wrote on Sophia Loren, which was published in 1969, I would not have been there. There was this modest short film festival in Trento and I wanted to go there, a moment to get to see Sophia Loren. I was guessing that I would be allowed to go there, unlike the situation of a big festival, such as the Venice film festival, where you had to be invited. I had been to Italy three times before 1990. During one of these trips, I took an interview to Sophia Loren at her home, in Marino. It was precisely during those days that Fellini was shooting Amarcord. This was just the kind of luck that overcompensated everything and all else. He was shooting, as usually, in the studio, at Cinecittà. He had built places of his hometown Rimini: the high school, the Fulgor cinema, the main square. More real than any other reality.

My adventure began with Unitalia, a sort of RFC, asking those there to allow me to go on Fellini’s sets. A man named Bersani warned me: ‘Miss, recommendations don’t tell Fellini anything. Who wants to be around him must commit to a sort of hunt. We will give you a permit to enter Cinecittà and the set. Stay there. A day, a night, because he also films at night. As he is very curious when it comes to new faces, he will come and ask you who you are. The rest is up to you.’ In short, this is what I did. I sat for a day, no one noticed me. A sat another day, no one took notice. But neither did anyone come asking about my business there. I was seeing the filming and taking notes. The third day the wonder had occurred. Fellini approached me and asked me directly: ‘Good day, are you the wife of the Polish filmmaker?’ He was talking about Roman Zaluski, who also came to watch il maestro at work. I answered no, I am a Romanian journalist who’s enjoying the privilege of being there. I don’t know what else I answered, I was too excited. The next day, he approached me again: ‘Ah, yesterday I confused you. Now I know, you’re the Dutch journalist.’ I said that I am neither and that I am still the Romanian journalist. I should have guessed his game; I had read so much about his ludic spirit. During my week-long stay there, his collaborators told me much about the pleasure he took in playing. Some of his games I caught on to, others, not. I did not know how to join the fray. It was difficult not to lose yourself, to dismiss the awe of witnessing the birth of a film by Fellini. It was the great encounter of my professional life. But I wrote all about it at the time, in Flacăra. What I wasn’t able to describe then was the feeling of piety that emanated from every member of his crew, when they followed him from set to set, a sort of holiness shown to a very close and tangible being. As one who had come from very far, such as I, it was no way you wouldn’t be intimidated, but the man himself was not. A ‘goodbye’ with Fellini always ended with ‘Ci sentiamo’ (I’ll be hearing from you over the phone), his passion for talking over the phone being well-known. This ‘Ci sentiamo’ echoed in my ears for years to come, and the last day I left the set walking backwards so as to not lose any portion of the shot’s filming.

Another important moment, which you have also evoked, was meeting the actor Zbigniew Cybulski, in Poland.

I went to Poland a lot. I would say about 16 times. My first trip there was as a journalist for Flacăra, which had an exchange with the illustrated magazines in socialist countries, which was a very good thing, that’s how we managed to go to Poland and Hungary. Generally, every country I visited I insisted on meeting filmmakers more than getting to know the places. I think that there was also the ego of youth at play, much stronger then than timidity. When I first arrived in Poland, I was dead set, of course, on meeting Andrej Wajda. As he was out of the country, I moved on to number two on my list, Zbigniew Cybulski – this Polish James Dean, as he was called. It’s one of the more chilling memories I have because I met him three weeks before he died. I was at the journalists’ restaurant in Warsaw with a colleague from the Polish magazine, when Cybulski made his entrance in the room. I was under the impressions that Maciek Chelmicki himself, the hero from Ash and Diamond, had entered. He had a similar model of blue jeans suite and his ever-present black sunglasses. He was young, 38 years old, but he looked even younger. I don’t know what got into me, during my interview with him, to ask him: ‘Can you imagine how you will look over a few years, what other roles, of utter maturity, you will be playing?’ I remember he caressed his hair with his hand and said: ‘But who knows how I will end up…’ Three weeks later he died, run over by a train he was running to catch, like in one of his movies, The Generation. Because he had acted in so many plays in France, his French was impeccable. He had this phrase he kept on repeating, when he described the actor’s work: Il faut chercher la rose. I met many people in Warsaw, where I often went because I was invited at the Cracow Film Festival. In the end, I got to meet Wajda as well. If I name Skolimowski, Polanksi, Zanussi and also the theoretician Jerzy Toeplitz, I believe the family of great Polish filmmakers is complete in my notebooks. I am not less prepared when it comes to Italians, because, with the exception of Fellini and Sophia Loren, I had the chance to meet and chat for long hours with Marco Bellocchio and Enio Morricone.

I assume that the Revolution felt as a form of liberation. Right after you were given the chance to write again, and not just for any newspaper, but for one of the most known ones, Adevărul.

It was a liberation, yes, especially because my hope was wearing thin. I was 50. And yet, there is a destiny. In 1990 I was invited to be part of the grand jury of the Clermont-Ferrand Festival. They had invited me before too, but each time I had to reply that I was ill. All of a sudden, I was colleagues with André Téchiné, Jean-Pierre Léaud (Truffaut’s actor) and Suzanne Schiffman (his screenwriter). This is how I became part of the Truffaut family and the Les films du carrosse society, and also how I got to write my book on François Truffaut.

I also went to Cannes. Cristian Tudor Popescu pushed me. I was so lucky, after the hiatus when I had no cinephile chief-editor, to have met, many years later, a man who loved and understood film. I began by writing an article for Adevărul literar și artistic. From an article I ended up being responsible for an entire magazine page, Traveling, and the weekly newspaper chronicle. Then there were more, a television program and a daily TV chronicle, all this for some years. Sometimes I desperately look at how much I could write during those years (she laughs – author’s note). For me, Adevărul was truly a platform that sustained and encouraged me, professionally. I was able to write about anything I wanted, to the best of my abilities. Even when it so happened that he wouldn’t agree with some of my chronicles and the ideas put forth, Cristian Tudor Popescu never altered a single word.

The fact that I wrote for one of the main newspapers was the best recommendation that the festivals that have invited me over the years took account of. I tried to do a certain kind of film criticism, in which there was a cultural centerpiece, analogies with other arts. This is what criticism is to me – to not enclose yourself in the respective film as in a particle floating isolated, without any connection to the Zeitgeist. This is what I was able to do at Adevărul. It was an age in which journalism was deserving of its name. Now it is all in shambles. Newspapers gave up on the culture rubrics. They are called Entertainment, Lifestyle, etc. Unfortunately, many talented and hardworking young critics must now fight on their own to gain status without the consequent support of magazines, support they are well-worth deserving of.

You mentioned the Cannes Festival where you also started going to during that time.

Since 1995. I visited France every year, for the Clermont-Ferrand Festival, after which I would stay in Paris for about a month at the Les Films du carrosse society, where I worked on my book on Truffaut. As I was saying, CTP pushed me one day, asking me, out of the blue, why don’t I go to Cannes. It hadn’t even crossed my mind. Cannes was not included in my job description, even though it was not that impossible then. I had befriended Truffaut’s widow, Madeleine Morgenstern, who had a certain preference towards Romania, due to her mother having been born in Oradea. I could have brought up the subject, but I hadn’t thought about it until Cristian encouraged me to. Romanian journalists had started going to Cannes, others than those from the Cinema magazine – Tudor Caranfil, Eugenia Vodă. It was through Madeleine Morgenstern that I finally had the privilege of meeting Gilles Jacob, the one who invited me.

What is it that fascinates you most about the festival?

Now, joking a bit, some of the films screened at Cannes can be seen just before the festival’s opening day. The first years there I was living the joy of being one of the few privileged ones who could see all those marvelous films before the others. The joy of writing about them. It gave you a rush of frenzy that made you capable of facing up to the effort. That of being the correspondent of a big daily paper involves a considerable effort. I have never been a compulsive critic. I never set to bring down records, I never listed the films I watched, but it is a must to at least see four films a day and write about them. Each day, too. You start feeling the rush of urgency that makes you vigorous and, so, you outrun the fatigue, because, otherwise, Cannes, as someone said, is a killing festival. It is the only festival in the world where, for years and years, press screenings would start at 08:30. This is not easy for a person – I do confess – has their fixations, such as I have. I like to sit in a certain part of the room and, always, at the first seat of the row. As if I wouldn’t want to share that darkness of the room with the other people there. To occupy such seats, you always had to be there earlier than most. You enter a whirl that seemingly carries you. Around the middle time of the festival, you feel as if your life force is dripping out of you. You have to recharge your batteries. If you manage to get over this hillside, you are ready to go at it again. Then, at the end of it all, you almost feel sad that it’s over. This is the paradox.

How do you see the state of film criticism today? It seems to be a profession that has been going for quite some years through some major changes once the Internet and social networks set roots, and also through a drop in the force of influence and aggravation of precarity.

For a long time, this has been a profession that found itself at a crossroads. Many years ago, I would meet with Antoine de Baecque at Les films du carrosse, a well-known film critic and, from my position of critic of cultural practices, we would often discuss about what’s happening with our profession. Antoine had a wonderful saying: “We’ll either be mummies or sentinels”. The mummy-critic is a being made of parchment, so-to-say, who closes off their multi-layered knowledge, but who is not needed anymore. It is accepted because it is a part of a past landscape. The sentinel is hanging by a thread to not let any impure elements fall through the net. So that we remain what we once were, the intellectual elite. That age has, too, passed. We are neither mummies, nor sentinels anymore. I ma not saying that it is an anachronical, old-fashioned, useless profession, necessarily, as I have heard and read many times over, but it is not the same. The huge liberalization of this profession, the one that the technologization of society made possible, has blurred the borders not only between the cinema journalist, the cinema chronicler and cinema critic – the classic distinction, but between all those that speak their mind, one way or another, critics, bloggers, vloggers, podcast hosts, and, lately, influencers. In the public mind there is this amorphous mass and the university critics. It seems to me that this type of barrier never existed in our case as it does today. As if a worthy, notable critic can educate themselves in the absence of theoretical support.

What would the role of criticism be today?

Essentially, I believe that the role of criticism is the same as before. It’s just hard now to pretend that you can discover something for the public, for those who read you, because sometimes they can see the film before you can, waiting nicely for the cinema room screening. What is left for you to do is to establish a communication pact, ‘the generosity pact,’ that Sartre spoke about, to try and find what brings you closer to and what drives you apart from your audience. A critic cannot godfather a better director, but I believe that they can form a better viewer, they can teach him where to find emotion and how emotion is built in a film. Technical references are available today for everyone to grasp. If the public—critic dialogue is limited only to the egotistical use of notions, I do not know what will become of our profession. Maybe we ought to give the new generation of film critics the time to discover a new, better path.

This article was published first in the 2022 printed issue of the magazine, still available in our online shop.

Journalist and film critic. Curator for some film festivals in Romania. At "Films in Frame" publishes interviews with both young and established filmmakers.