On Uppercase Print, with Gianina Cărbunariu, Ioana Iacob and Șerban Lazarovici

Uppercase Print, the newest fiction feature by the prolific Radu Jude will take part in the 70th, jubilee-edition of the Berlinale as part of the Forum line-up, along with his newest documentary, The Exit of the Trains – an absolute premiere for a Romanian director. Starting from Gianina Cărbunariu’s eponymous theatre play, the film stages the story of teenaged dissident Mugur Călinescu, who, in the fall of 1981, scrawled a series of anti-system manifestos on the walls of the Communist Party Central Committee in Botoșani and who, just four years later, died of leukemia, even though some suspect that he might have been poisoned or irradiated. Between scenes based on documents and wiretaps put together by the Romanian secret police, acted out in a Brechtian manner, the film also weaves in an ample and kaleidoscopic selection of National Television archival footage shot in the same year, an entire audiovisual universe that acted as a concealer to the world that Mugur Călinescu abhorred. The film is also slated to be released in local cinemas, starting with the 21st of February.

Being a film at the crossroads of theatre, cinema, and history, we decided to talk to three of the people who were involved in Uppercase Print, who can share valuable insights on these three topics: director Gianina Cărbunariu, actress Ioana Iacob și debutante Șerban Lazarovici, who, in his day-to-day-life, studies at the same high school as Mugur Călinescu did.

Gianina Cărbunariu, on the origins of the play and script

Gianina Cărbunariu is a theatre director and the director of the Youth Theatre in Piatra Neamt.

I’d like to start out by asking you about the play that lies at the basis of Uppercase Print. What attracted you to the story of Mugur Călinescu? How did you document his case?

Before Uppercase Print I did a play starting from ten pages of a transcript that was a part of the secret police (Securitate) dossier on Dorin Tudoran, a poet and journalist. In both plays, I was interested in the mechanisms through which a secret police dossier was created, along with exploring what reading such documents nowadays might entail. I spend a couple of months in 2011 and 2012 reading different dossiers at the National Council for the Study of the Securitate Archives. Beyond particular cases, my questions were always circling the way in which a given society relates to such archives – which are, in fact, some traces of realities. For my play, X mm out of Y km, I had the chance to discuss with Dorin Tudoran, who was kind enough to answer my questions about how that specific transcript was written, while for Uppercase Print, I had the support of two local historians, Mihai Burcea and Mihai Bumbeș, who put at my disposal the „The Panel” and „The Student” dossiers, along with some documentation they had worked on in 2007: interviews of former secret police officers who had worked on the case in 1981, interviews with Mugur’s mom and with one of his former classmates. I think that recent history should be revisited, first of all, due to all of the consequences we have been living through in the past thirty years. I wasn’t interested in making a play about the past or about history, but one that would have a certain relevance for today’s world, one in which, oftentimes, surveillance, a lack of reaction, opportunism and manipulation have taken different shapes, which are much more diffuse, but probably as destructive as the old ones.

The post-modernist approach of the play is spectacular since it places at its very center the document within documentary theatre. How does this influence the process of narrativization of the text and performance, and how do you believe this has translated into its cinematic adaptation?

The entire play is a sort of invitation for the audience to read a document together with the artistic team. The text is integrally sourced to the dossier, not one single line belongs to me, as a dramaturgist. The direction and dramaturgy of the play consisted in imagining the situations in which this text was produced: written (in the case of declarations, files, action plans) or spoken (in the case of phone calls and wiretapped discussions in Mugur Călinescu’s home or at his meeting with the school inspectors and teachers). Because oftentimes the documents in the dossier were set in an order that was not chronological, I made a selection and rearranged the materials to reconstruct important moments or to focus on certain themes.

If in the case of the play, the aim was to render documents visible and to propose its interpretation by imagining a possible context for it, I think that in the case of the film, the acting style reproduces in a way that is as neutral as possible a type of language that is extremely standardized, which is a way of translating this choice of using ready-made materials (meaning, the two dossiers). Moreso, the final edit, which uses archive materials from the archives of the Romanian National Television brings together two types of language that reveal new meanings through unexpected associations.

How did you collaborate with Radu Jude on adapting the play into a film? (You also have a small cameo at the very beginning, along with some of the actors in the original production of the play, which was staged at Bucharest’s Odeon Theatre.)

With Radu, I share an interest in archives, in questions related to documents of our recent history, for ready-made materials. The expressive means of theatre are, however and quite obviously, very different to those that cinema has. The script that I used for the stage is almost identical to the one that is used in the film (which uses some more fragments in the dossier), but its concept, the usage of the dramatic text completely belongs to Radu, who is experimenting his ways of seeing the world and cinema as an art form in his own style.

There are abundant formal references in the film regarding epic theatre and the conceptual apparatus of Bertold Brecht, which elicit the V-effect (the distancing effect) in the audience. How do you see the ways in which theatre and cinema may coalesce and intersect, beyond the area of „conventional” immersive adaptations?

I believe that there are many examples of „contamination” both in the 20th century and at the beginning of the 21st. Many theatre directors of the past twenty years, especially when they have the resources to do so, use a certain kind of cinematic language onstage, which acts as a potential to the theatrical means that they already have at their disposal, which sometimes leads to spectacular results, especially if there is a strong underlying concept. Using instruments that are specific to cinema in theatre may produce this „distancing effect” which aims at catalyzing a reflective process. The same thing happens, I think, in cinema as well, when a certain convention appears which belongs more to the sphere of theatrical language. In what concerns myself, I try to enter a dialogue with artists that have different backgrounds, be it visual artists, musicians, choreographers or playwrights. These are experiences that take you out of your own comfort zone and that make you capable of reevaluating your own work, your own language. That happened now as well when I was on set for Uppercase Print, and for that, I am very grateful to Radu Jude.

Ioana Iacob, on the intersections of theatre and cinema

Ioana Iacob is an actress at the German National Theatre in Timisoara. This is her second collaboration with Radu Jude, after “I Do Not Care If We Go Down in History as Barbarians”.

How was it like to collaborate again with Radu Jude but also with Șerban Pavlu, considering this film is made in a formal key that is quite different from the one used in „… Barbarians”?

To me, the chance to meet Radu and Șerban is always a great joy, no matter what the structure of the project or the main key of the film is. Obviously, in contrast to „Barbarians”, my input here was much smaller, and by means of acting were completely different, but I am happy for every single challenge. Even more so, I am happy to work with people whom I appreciate, and that is very important to me. I’ve had projects in which, even though they’d seemed interesting in the beginning, ended up not meaning much in the end to me, precisely because I didn’t resonate with the people that were involved in them.

Even so, in a certain sense, one could see Upper Case print as a sort symbolic of a successor to Jude’s previous film, in terms of its formal and thematic project. As an actress that is principally active in theatre, how is it like to work on a film that has a strong relationship to it – either through its theme or construction? How do these aspects inform your work?

I wouldn’t call this film a successor strictly because Radu has again chosen a subject that is closely related to sociology and history – certainly, his preoccupation for such themes did not start with „Barbarians”. As for the possibility that his recent films are (or aren’t) subject to a certain artistic formula, I don’t know, I would rather let people who are more knowledgeable about this to talk about it.

I think that both theatre and film can be subject to different kinds of methods in terms of approach and construction, and the two art forms can be mutually influential – they can coalesce, they can divide themselves, they can even fight each other. Theatre can be a part of cinema and vice versa. It is true that sometimes the film’s set design made me feel like I was in a theatre, but this sensation vanished once they shouted „Action!” and I was in front of the camera. I’m happy that I could do both. The means of theatre differ in comparison to film, but I believe that both keep the possibility of experimentation open and I’m eager to do it again, both on stage and on a film set.

You play the role of a mother that (ultimately, unsuccessfully) tries to save her son, a position that is very dramatic, but in a Brechtian convention, that minimizes emotional output. How was it like to meld together these apparently antinomic positions?

Now that I’m thinking about the film, this style of acting seems very appropriate to me, even though I did have some questions in the beginning. Still, the script is mostly composed out of (official) declarations, and even though these could have been acted out differently, I think that the underlying choice of such an interpretation is to make the information that the character speaks out arrive in a clear and unaltered way to the audience. I entered this convention and concentrated on what the character had to say, not on what she had to live through. It might seem contradictory, but it’s not, it’s a matter of choice.

As an actress that has strong ties to the local German community, how do you see this mix between epic theatre and cinema that Radu Jude proposes in this film? Might Brecht and Piscator be more relevant than ever?

This approach is always interesting to me, and not just because I have connections to the German Theatre. I like it when the „sacred space” is „contaminated” and when the actor is simultaneously a god and a human, not just a character – because this is where nuance is born, plans are multiplied, the audience can have a much larger experience and isn’t condemned to just feeling. And yes, I believe that the socio-political should be strongly present in any contemporary art form, while still leaving due space for the artistes. (laughs)

Șerban Lazarovici, on his debut role and Mugur Călinescu

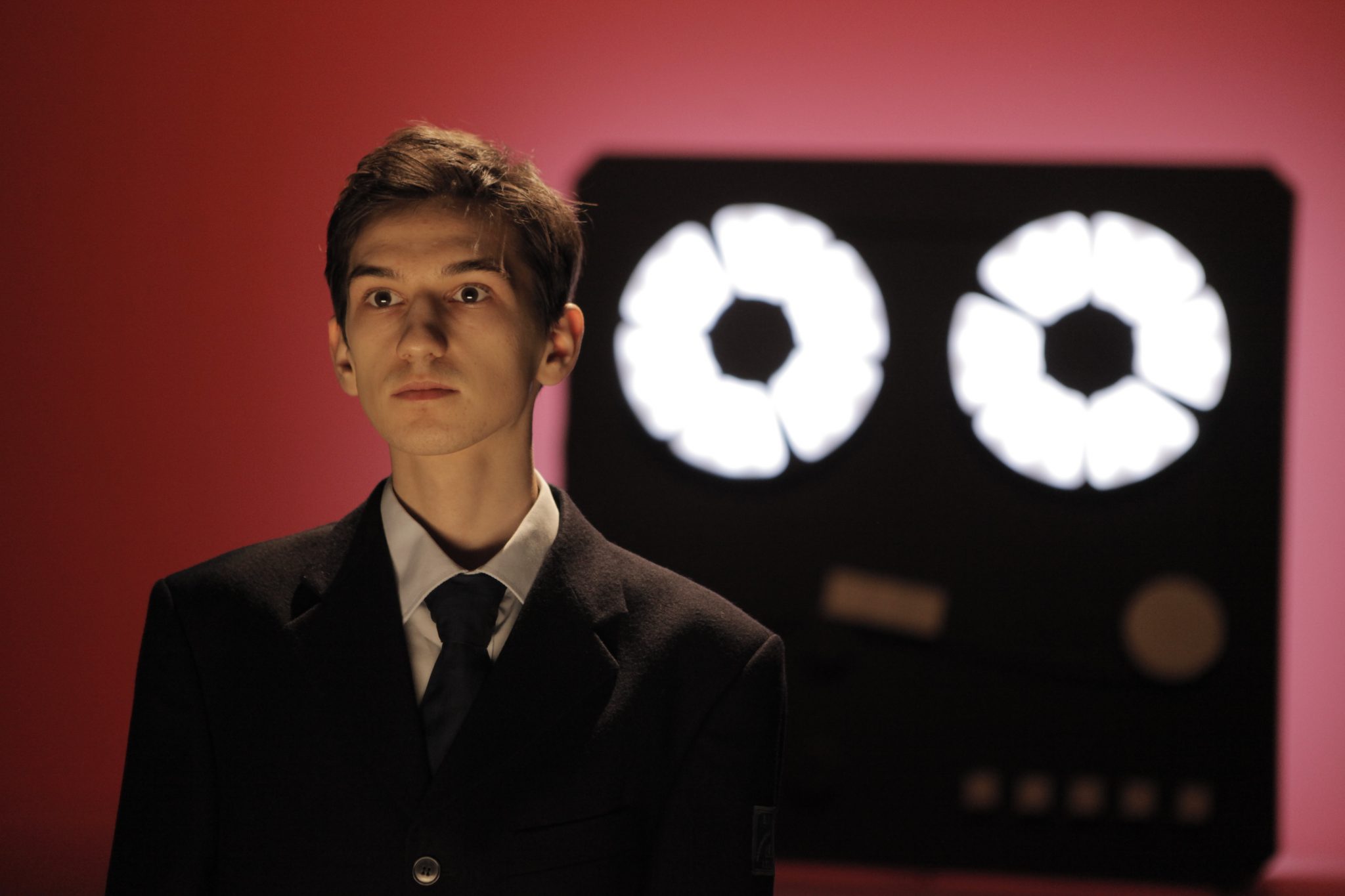

Șerban Lazarovici is a young actor and a student of the „A.T. Laurian” National Collegium in Botoșani. Uppercase Print is his first role in a film.

How was it like to act in a film for the first time? How was your time on set and what did you learn from this experience?

A film was the kind of experience that I only dreamed about when I was in high school. It was a dream that came true much faster than I thought it would, it never even crossed my mind that I would get the chance to act before I graduate. I always thought about how it must feel behind the camera. I think that the first day of shooting on set gave me the answer to that question, and I think that the thing that impressed me the most was the professionalism. That was also when I realized that this wasn’t child play anymore, to say so, but that I was part of a serious project.

How was it like to enter the skin of Mugur Călinescu? How did you prepare for the role?

Mugur Călinescu’s name is often heard in Botosani. Especially since the town is small, you always somehow meet people who were in contact with him. That’s why I also felt a slight pressure when I thought about the local audience. I don’t know how people are going to react to the film and especially how it will make them remember Mugur. When I found out that I was going to play his part, I started reading more about him, but I also tried to put myself into his shoes. A couple of times I went for a walk through the places he used to go at night so that I could imagine just how strong his feelings were about what was going on at the time.

You study at the same high school that Mugur Călinescu studied at and, while shooting, you were the same age as he was during the plot. How do you relate to his figure and his acts of civil disobedience, nearly 40 years after his protests? Are there things you empathize with directly?

Mugur is a hero to me. I don’t think that I would have had the courage that he had back then. A thing with which I do empathize, however, is his wish for a change – it’s a feeling that I also have sometimes, but which I wouldn’t be courageous enough to manifest in the way that Mugur did.

Do you think there are things about Mugur Călinescu that go beyond the specific historical and political moment in which he was living?

I think that beyond his status as an anti-communist dissident, Mugur was, though his repeated appeals for freedom, a model for our current society. His manifestos speak about human rights, about liberties and about change, aspects which are very much discussed in contemporary society – one that would like to be the exact opposite of the one in which Mugur was living.

Title

Uppercase Print

Director/ Screenwriter

Radu Jude / after a play by Gianina Cărbunariu

Actors

Șerban Lazarovici, Ioana Iacob, Șerban Pavlu, Alexandru Potocean, Constanting Dogioiu, Bogdan Zamfir, Ilinca Hărnuț

Country

Romania

Year

2020

Distributor

Hi Film Productions

Film critic & journalist. Collaborates with local and international outlets, programs a short film festival - BIEFF, does occasional moderating gigs and is working on a PhD thesis about home movies. At Films in Frame, she writes the monthly editorial - The State of Cinema and is the magazine's main festival reporter.