Roxana Stroe: “I see cinema as a means of escapism”

Roxana Stroe’s “A night in Tokoriki” (2016) is probably the most popular Romanian short film in recent years. The film was awarded at the Berlinale, in the Generation 14plus section, as well as at Transilvania IFF, and was selected at several other festivals, being highly praised both by juries and the public. The story takes place at the end of the ‘90s, in a village in Romania, in an improvised nightclub called “Tokoriki”, where a girl is celebrating her 18th birthday and her boyfriend turns to be the crush of another boy. What’s special about “A Night in Tokoriki” is that it has no dialogue, the whole story is supported by a soundtrack consisting of popular songs of the era. The main cast includes Cristian Priboi, Cristian Bota and Iulia Ciochină.

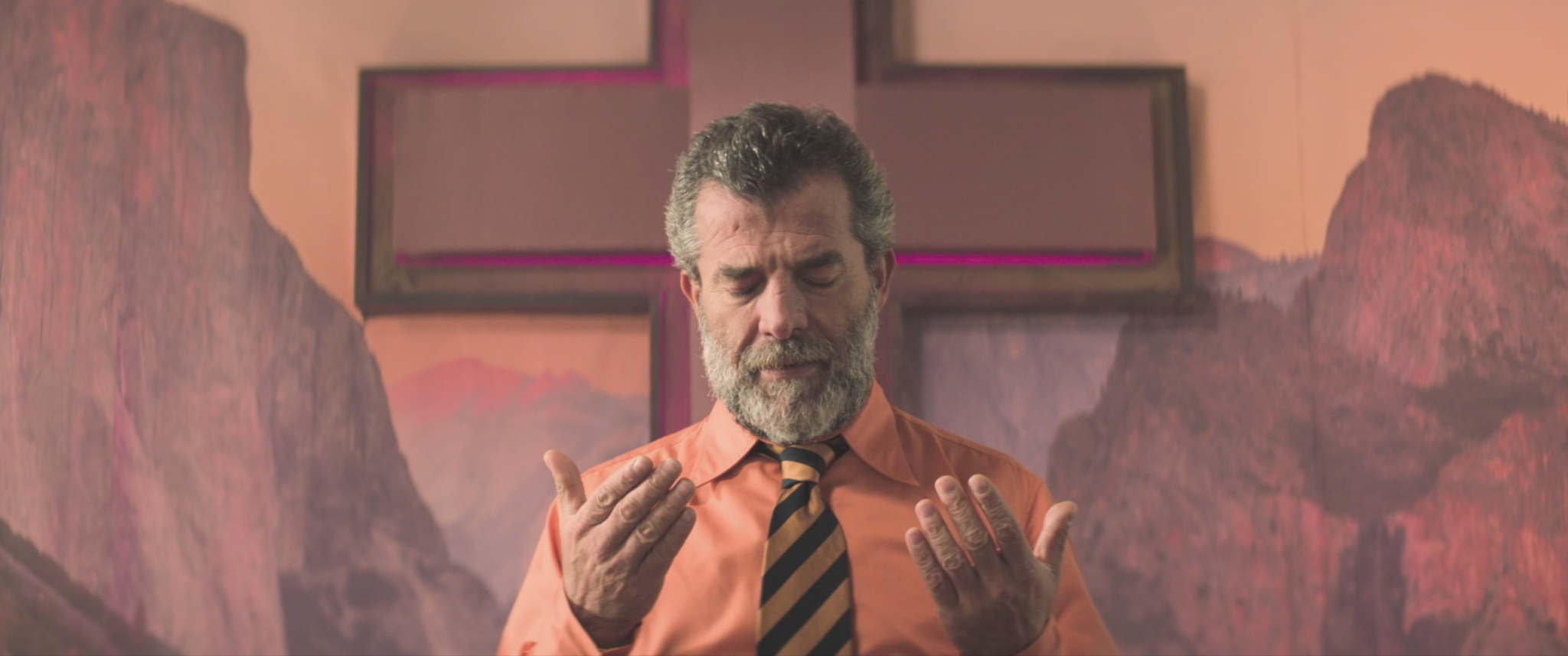

A forbidden love story, set in the 2000s and depicted in a similar way – with no dialogue and supported by music – also makes the subject of “Appalachia” (2022), Roxana Stroe’s latest short film, which recently had its world premiere at the Festival International du Film Francophone de Namur. A Romania-France-Belgium co-production, featuring a cast of French and Romanian actors, “Appalachia” revolves around a boy (Phenix Brossard) who falls in love with a girl (Zéa Duprez) whose father (Costel Caşcaval), the leader of a religious cult that uses snakes in their rituals, is against the relationship.

Both films were co-written by Roxana Stroe and Ana-Maria Gheorghe, who also collaborated on “Black Friday” (2015), a student short film set in the ‘80s, when the food queues bring a man (Gabriel Spahiu) to despair and he starts shooting people in order to get his food ration.

Born in September 1991, Roxana Stroe studied Directing at the UNATC (2010-2015) and is one of the most promising young directors, showing a unique style, different from the usual realism approached in Romanian cinema.

With the release of her newest short film, “Appalachia”, which will also be screened at Les Films de Cannes à Bucarest, I invited Roxana Stroe for an interview for our Emerging Voices column.

You’ve been off the grid for a while. Why did it take so long to come back with a new short film?

A Night in Tokoriki premiered in February 2016 at the Berlin Film Festival. That year was only about touring the festivals with the film. A Night in Tokoriki had a long festival run, about two and a half years. Even this summer, there have been requests from festivals to include it in programs dedicated to favorite short films over time. Obviously, I was glad that it had such a great run.

So it wasn’t until the end of 2016 that I started thinking about a new project. I met with Ana-Maria Gheorghe, with whom I co-wrote A Night in Tokoriki and Black Friday, my student films, and we decided it was time to make another film. That’s how we started working on Appalachia, which had a different title initially. We went through several versions of the script. The following year we applied for funding at the CNC.

But we didn’t get financing and things didn’t work out, so I put it aside and started making commercials; I entered this area because ultimately you need to make a living. I realized that things don’t come so easily together in cinema. I didn’t necessarily expect it to be easy, but I was encouraged by how well it went with A Night in Tokoriki. It’s true, I went quite far with Appalachia. For a short film, it was expensive. The feedback I got was that it’s not worth making such an expensive short film, that it costs as much as a feature film and you don’t get your money’s worth. In general, people are not interested in investing in something that brings no money. So I left it aside and we moved on.

Around the beginning of 2019, I started thinking about it again. I just couldn’t give up on it, I had to try again. I hadn’t even begun to write something else, my mind was set on this one. So I read it again to see what I could do, what I could take out, how I could rewrite it just to give it one more try.

I get demoralized quite easily. I know it’s wrong, but that’s just how I am. If I get rejected once, I won’t come knocking on the door the second time. There are people who apply six or seven times until they get financing from the CNC. If I’m rejected, I’ll think that my project is terrible, that this job is not for me. To be honest, I’m quite dramatic: I should quit and do something else, it was wrong to choose this profession. It takes me a while to get back on my feet and start again.

What about the success you had with A Night in Tokoriki, didn’t it make you more confident?

It wasn’t enough. I thought that what happened with A Night in Tokoriki was just a happy accident, a one-time thing. It’s not okay to be like that, it’s rather harmful. You need to hold your ground, to struggle, and if one door closes, you enter through the window. That’s the mindset you need to survive in this industry. It’s a jungle. Instead of wasting time dramatizing that the selection board didn’t like your script, you should look at what they didn’t like or realize that maybe the board wasn’t the best fit for this kind of project, and just keep going. You need to look at the situation from every angle. It just took a while to decide to rewrite it. I rewrote some scenes. I removed some characters. I made it more simple.

In the fall of 2019, I worked with Gabi Suciu on a commercial. It was late at night, we had just finished shooting the commercial and we started talking. I told her that I have a project and asked her if she could look over it and tell me if there was any chance to do something with it. She read the script by the next day and told me that what I wanted to do was difficult, that it was quite a struggle production-wise, that it entailed a lot of work, but that we should take it step by step and see what can we do. She made a list of pitching programs, where you can find co-producers, and the first one we applied to was the Euro Connection program from Clermont-Ferrand. A month or two later we got the answer that it was selected. In February 2020, we presented the project there. We found a French co-producer who we thought could make things happen in France. The first positive response was from the French CNC, which was very encouraging. Then there was the Wallonie-Bruxelles fund in Belgium, where we also had a co-producer. It was only in 2021 that we were able to apply to the Romanian CNC because no funding session was organized in 2020.

Appalachia, just like A Night in Tokoriki, has no dialogue but instead features a lot of music, especially extra-diegetic songs, which helps to portray the characters and push the story forward. Why are you fond of this type of cinema?

I’m interested in this type of cinema as far as my own films are concerned. But I do like films with dialogue. In fact, I have several favorite movies, which I consider masterpieces, that have dialogue from start to end, such as 12 Angry Men or Sunset Boulevard. Indeed, music plays an important role in my films, but I’m sure that in the future I will try different approaches, where there won’t be so much music. Still, the visual aspect will continue to be just as important. The idea of trying to tell a story using only images was the first thing that attracted me to this type of cinema.

In Appalachia, the music is called on by the characters. In A Night in Tokoriki, it’s the other way around, it all starts from the music. I remember that I was in the second year of my master’s and I had to make my graduation film. Up to that point, you think that the world is yours; you are a student, you have no worries. But then I started to get a little choked up: I finish film school and then what? I became nostalgic, I was searching for something. I started listening to the songs of my childhood and made a playlist that I put on repeat. And one evening, I thought how cool it would be to make a film that takes place in a disco club and only features these songs. That’s how it started. With Appalachia, I think subconsciously I was influenced by A Night in Tokoriki and its course, so it’s like a follow-up.

Do you feel you’ve defined a style of your own?

I don’t know. I’m still searching. But what I can say for sure is that the focus on the visual aspect will remain. That is definitely part of my style. I don’t even know exactly why it attracts me so much. I can’t really explain it. I recently discovered Yann Gonzalez and I’m fascinated by his aesthetics. I even saw some videos he made. I see myself in his approaches in terms of chromatics and light. I find him outstanding in this sense.

I think what attracted me to cinema is that it’s a complete art. If you do not use lights, music, or chromatics, I feel that you are not using this art to its full potential. That is what fascinates me. I’ve seen a lot of movies that depict incredible stories, very moving, but they’re not rendered to my liking. They don’t have that glitter that dazzles you. Something seems to be missing. For me, that is the beauty of cinema, this flamboyant detail. But I watch all types of films. I know how to appreciate a good story. Still, when it comes to my own work, I have to add some glitter, some bows and ruffles.

How do you write a screenplay that practically has no dialogue? Is it easier for you?

I have an issue with writing dialogues. When I was in development with Appalachia, I added some dialogue in the last drafts of the script, following the feedback I got from producers, but I eventually dropped it. I thought the lines sounded unnatural. Some people have a knack for writing dialogues. It really is a talent. But I lack it. Both A night in Tokoriki and Appalachia have a lot of descriptions and action.

Do you think you could make a feature film like that?

No. It’s not impossible to make, but I don’t think anyone would pay a ticket to see a video of an hour and a half. That is why I said that I’m still searching, because I want to find the balance between the visual approach, where I try to tell the story through images, and the value words could add to it.

Both A Night in Tokoriki and Appalachia are basically love stories between people from different backgrounds, which raises many obstacles in their way. Why the interest in this structure?

I think that at a subconscious level this is how I perceive the beauty of love: in its impossibility. I think that true love has certain beauty when it’s tragic. After all, the narrative in Appalachia is based on Romeo and Juliet, nothing new under the sun. I wanted to show that Romeo and Juliet can also be told only through images. That is what appealed to me. I saw it as a challenge. The film has some cheesy elements, kitsch is my guilty pleasure.

Actually, the story didn’t start from Romeo and Juliet but from a photo I came across by chance, portraying an American pastor holding snakes above his head. It’s a ritual practiced there. I saw this photo and it hit me. I thought: that’s it, I don’t know how, I don’t know the story yet, but it will start from here. The whole story revolves around the ritual. I did some research on what this ritual entails. I found out that it started in 1900 and that it’s still practiced in the USA, even if many pastors died from snake bites. I placed it in Romania but in an imaginary universe.

Your films break from the realistic convention and rather belong to an imaginary, fantasy cinema. Where does this interest come from?

Probably because I see cinema as a means of escapism. For me, that’s the appeal – building a universe. I’ve taken a lot of heat for that, starting with Black Friday. Then with A Night in Tokoriki. Even with Appalachia, the local feedback was that its universe is not believable. It’s not Romanian. But that’s exactly the point. Many have said it as if it were a flaw, a disadvantage, but I don’t see it that way. I take it as a compliment: it means I’ve reached my goal. It meets my convention. You shouldn’t see my films as slices of reality. I don’t care about that. I lose interest if I have to portray reality as it is. Give me a true story and I’ll alter it.

Where does this come from?

That is just what appeals to me. Even before deciding to pursue filmmaking, the books I was reading were going in that direction. Anaïs Nin said that reality doesn’t impress her, that she believes only in infatuation, in ecstasy, and that when the banality of everyday life imprisons her, she finds ways to escape. All walls come down.

You feel that reality is all too grim and that is why you don’t want to reproduce it in your films?

I do, especially if we look at what happens now in certain places or countries. Then again, what happens in Romania is just as awful. I’m an empathetic person, but I try to hide it because I see it as a vulnerability, and people tend to take advantage of your vulnerabilities. I only have to see some news or hear a sad story for it to affect me more than I would like to admit. I know what it’s like to lose loved ones. We all go through some stuff in life that impacts us. Do you know that bittersweet taste? That is what I feel when faced with reality and cinema offers a way of escaping.

So cinema is also a way of protecting yourself?

In a way, yes. It’s like a shield.

Do you think films can have a similar effect on the viewer?

Yes, I do. But it depends on the person. It’s true, my approach is a bit self-centered because I focus on the stories I like and I make them my way, to my heart’s content. I’ve read about directors who say they think only about the audience, how to make them laugh or cry. That is not my approach. I think about the story, and if it tells me something, I dedicate myself completely to convey it through film.

What was it like in film school?

The first years, you barely realize what filmmaking is about. I got in right after high school, I had no experience. Out of 14 colleagues, half of us had just graduated from high school. There were only a few with some experience, who had worked in television or been on set before. I was a complete outsider, didn’t have anyone working in the field.

Things get more serious when you enter the master’s program. There are fewer students, there is more competition, you start thinking about what you will do with your life after you finish. There are many who finish this school and shift to other areas because they cannot find work here.

You also need to be a bit self-taught, practice is vital. Teachers show you some films and you analyze them, but it’s not enough. You also have to do some work on your own. I think it was Truffaut who said that he could happily spend his whole life watching three films a day and reading three books a week.

Film school is important because you join a group and develop a team. And it provides everything you need, from equipment to people who can help you build a set from scratch. Making films, that’s when you learn the most. You learn the basics, which is essential. If you don’t have a basis and you don’t know the rules, how can you break them?

Fortunately, you graduated with a film that ended up being a big hit, A Night in Tokoriki. How did you feel when you finished film school and realized you were on your own?

It wasn’t easy. I took the graduation exam in the fall, in September. My teacher, Ovidiu Georgescu, supported me unconditionally, and for that, I have a great deal of respect for him. He is an extraordinary man. But the other professors on the examination board weren’t too happy about A Night in Tokoriki and dismissed my work. When the exam was over, I got up and left the room without saying goodbye. Once out of the building, I started to cry. I usually don’t manage to hide my emotions, but this time I didn’t want to give them the satisfaction to see me cry. Between September, when the exam was held, and January, when I received the answer from Berlin, I kind of lost hope during these months. I was demoralized that I might not do anything with the film.

Being selected at Berlinale must have helped you regain your confidence.

Yes. But I want to be clear. Even though they dismissed my film, I still liked how it came out. I was demoralized because my work, my concept and my approach were not appreciated, and I was thinking about what I should do next, what direction I should follow. I was afraid I would encounter the same reaction wherever I went. I was criticized for everything, from the idea of the story to the cast and soundtrack, but I didn’t see anything wrong. That was my grief. Then, there was also the pressure that I finished school, I had no job and no prospects. So the good news that the film was selected at Berlinale was all the more significant. It was an unexpected surprise.

How did you become interested in filmmaking?

What I can tell you is that I used to write poems in middle school. I used to go to olympiads, to the Romanian language and the mathematics ones. I was a nerd. I graduated with the highest grade. The idea of getting a lower grade was an outrage (laughs).

Were you also a nerd in high school?

I finished high school with a slightly lower grade because of Physics. I didn’t like it, especially the problems.

To be honest, I found out quite late what a director does. But, in school, I had another passion. There was only one shopping center at that time in Constanţa. And when I was in sixth grade, a DVD rental shop opened there. It had loads of DVDs. On weekends, I used to go there with my parents: they would stop for a coffee at the mall and I would spend a whole hour just picking DVDs. I would take ten at a time and watch them that very weekend. Don’t imagine I was renting art films, I don’t think they even had any. I was taking horror movies and thrillers. That was what I was interested in at the time, movies with throats being slashed and blood spurting. There were two girls working at that shop, and at one point, one of them said to me: “Wow, you’re so cute.” And the other replied: “Cute? Wait and see what movies she rents” (laughs). I felt very proud, very cool.

Then, in high school, I had less free time. The rental shop eventually closed. In the ninth grade, I thought about going to dentistry or medical school. My mother was a pharmacist and she would always say that she should have gone to medical school because pharmacy school was a lot harder. In the tenth grade, we all decided that I should go to the school of economics, which was rather popular then. I had chosen the Faculty of Banking and Finance. My grandmother would urge me to become a teacher because I would have three months off a year. In the 11th grade, I was still sticking to the Faculty of Banking and Finance. But that same year we had the entrepreneurial education class. By the end of it, the teacher gave us a career test, to see where we are headed. It was a multiple-choice questionnaire, but quite extensive, it took us an hour to do it. He brought us the results and mine was the artistic field: director, actor, writer, painter. So I said to him: “Teach’, you must be joking, that test was a waste of time, I’m going to the economics school”. He looked at me and said: “Ms. Stroe, I don’t care one bit about your opinion. Regardless of whether you think my test is right or not, in order to pass my class, you have to bring me an interview with someone from the fields that came out on your test”. I went home outraged. I didn’t know what to do. My mom had a friend whose daughter was studying acting. She gave me the number of a teacher at her school, whom I could talk to. I went one evening after classes. I just wanted to take the interview and be done with it. I don’t remember what that woman told me, but it stirred something in me. Maybe it was her life story or the way she spoke to me, I don’t know what it was exactly, but it completely changed my course.

I started looking for theater and film schools in Romania. I found three universities: Hyperion and UNATC in Bucharest and Babeş-Bolyai in Cluj. Cluj was too far. Hyperion was a private school. That left UNATC. I saw it had a film faculty. I didn’t say anything to my parents at first. I was aware I would get big mayhem from them. The search process took several months. I was drawn to it. I didn’t know why exactly. At the beginning of the 12th grade, I decided that this is what I want to do. I told my parents eventually. Obviously, they didn’t react very well, they believed it was just a whim. In time, they realized that wasn’t the case and that this is what I want to do.

They agreed to let me go to the training classes the school held every Saturday. The classes were very helpful. I met some of the teachers, I was told which books to read, which films to watch, what the exam involved, etc. I went for a few months. I told them I don’t have access to films in Constanţa and they lent me the titles I needed to see. They even lent me books. I also bought film books from a bookstore in Constanţa. This whole thing with cinema and filmmaking, it just hit me. It was love at first sight.

I didn’t even consider another school. Which led to a series of arguments with my parents: “What if you don’t get in? All your classmates will be students, and you will waste a year at home”. It was just before the admission exam. I told them to stop bothering me because I would get in; it wasn’t like I sat around and did nothing all those months. It was hard to get in. We had three days of examination. I got in with the highest grade (laughs). After that, my parents started to support me unconditionally. Many times, when I encountered difficulties at school or came home crying after an exam, saying that I better give up and do something else, they would encourage me and tell me that this is my path and I have to keep going.

How do you see yourself now, as a young director who has made a few short films and wants to continue in this field, in a time when women filmmakers are finally gaining more visibility?

Ever since I got into film school, I felt that things were changing for the better. In the Directing section, we were half girls and half boys. There are more and more film festivals dedicated to female directors. For example, Zilele Sofia Nădejde also has a section dedicated to film and promotes short films directed by women. Until recently, film directing was considered a job for men. Few women dared to take this path. But it’s not the case anymore and I believe that in time there will be more and more such initiatives, which support women filmmakers and give them visibility.

As for myself, I’d say that what matters a lot are the people you surround yourself with. It’s important for there to be mutual respect. If the people by your side believe in you and the project, it no longer matters that you are a beginner. Things work out on their own and collaborations come naturally because there is a common goal above obstacles and everyone’s ego.

So my fears are rather of a different nature, like waiting I don’t know how many years to get financing. When your ideas are rather expensive and harder to materialize, it can take a very long time until you to get to make the film.

It’s not easy making independent films, relying on help from friends or colleagues. Once you finish film school and step into the real world, no one comes to work for free anymore, just based on the fact that you are friends. Everyone has to be paid. It’s hard to make your dream come true, it’s hard to bring it to light. That’s the biggest bump. Then there is the fact that what you make may or may not be appreciated. You may think you have something relevant to say, but you notice that the public doesn’t relate to the message you’re sending or the questions you’re raising. And that can affect your self-confidence, even your next projects, because you start doubting your ideas. This entire hiatus taught me that it’s not enough to have success with one film. It doesn’t guarantee the success of the next film. You always have to start over.

Journalist and film critic. Curator for some film festivals in Romania. At "Films in Frame" publishes interviews with both young and established filmmakers.