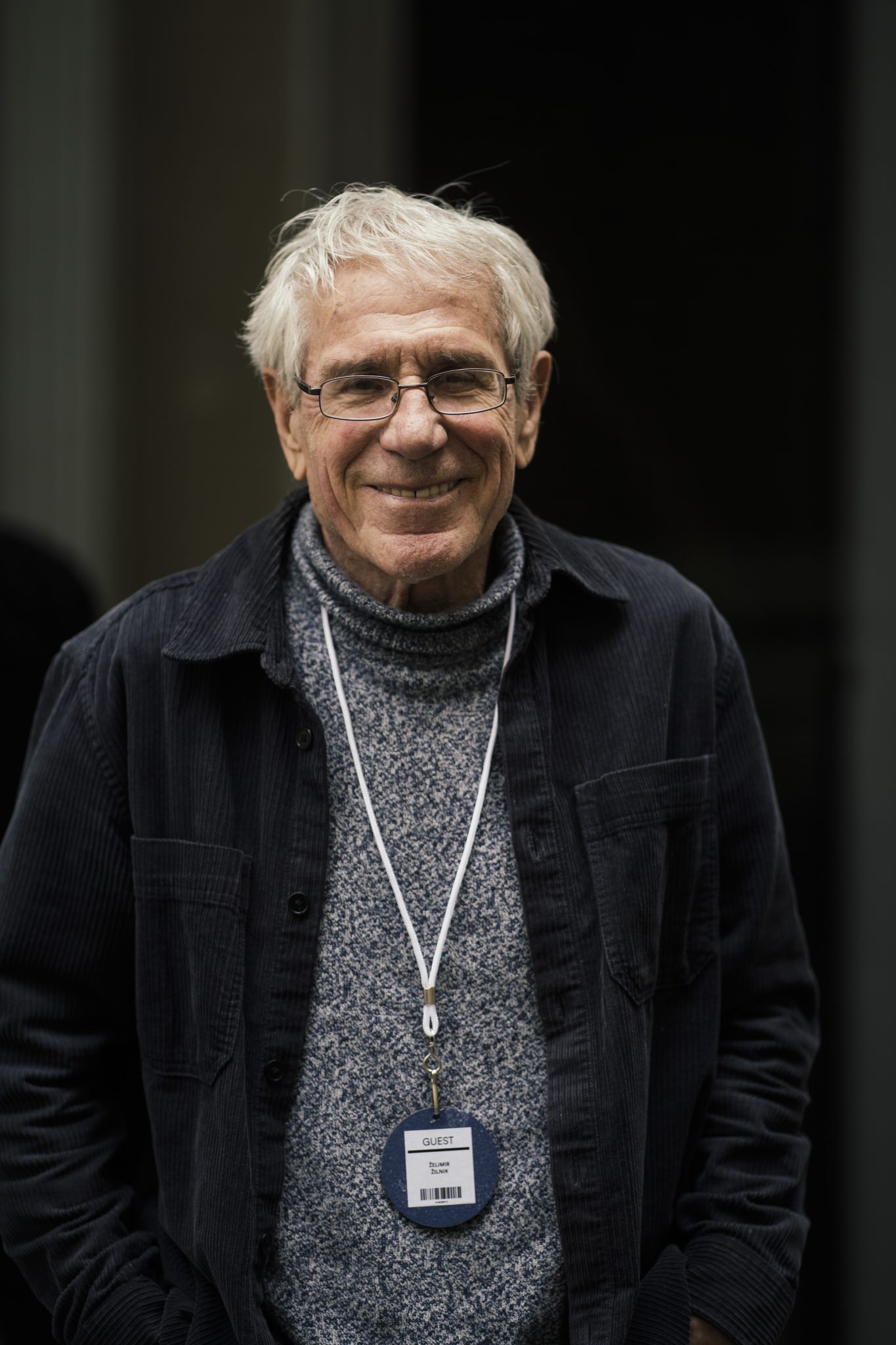

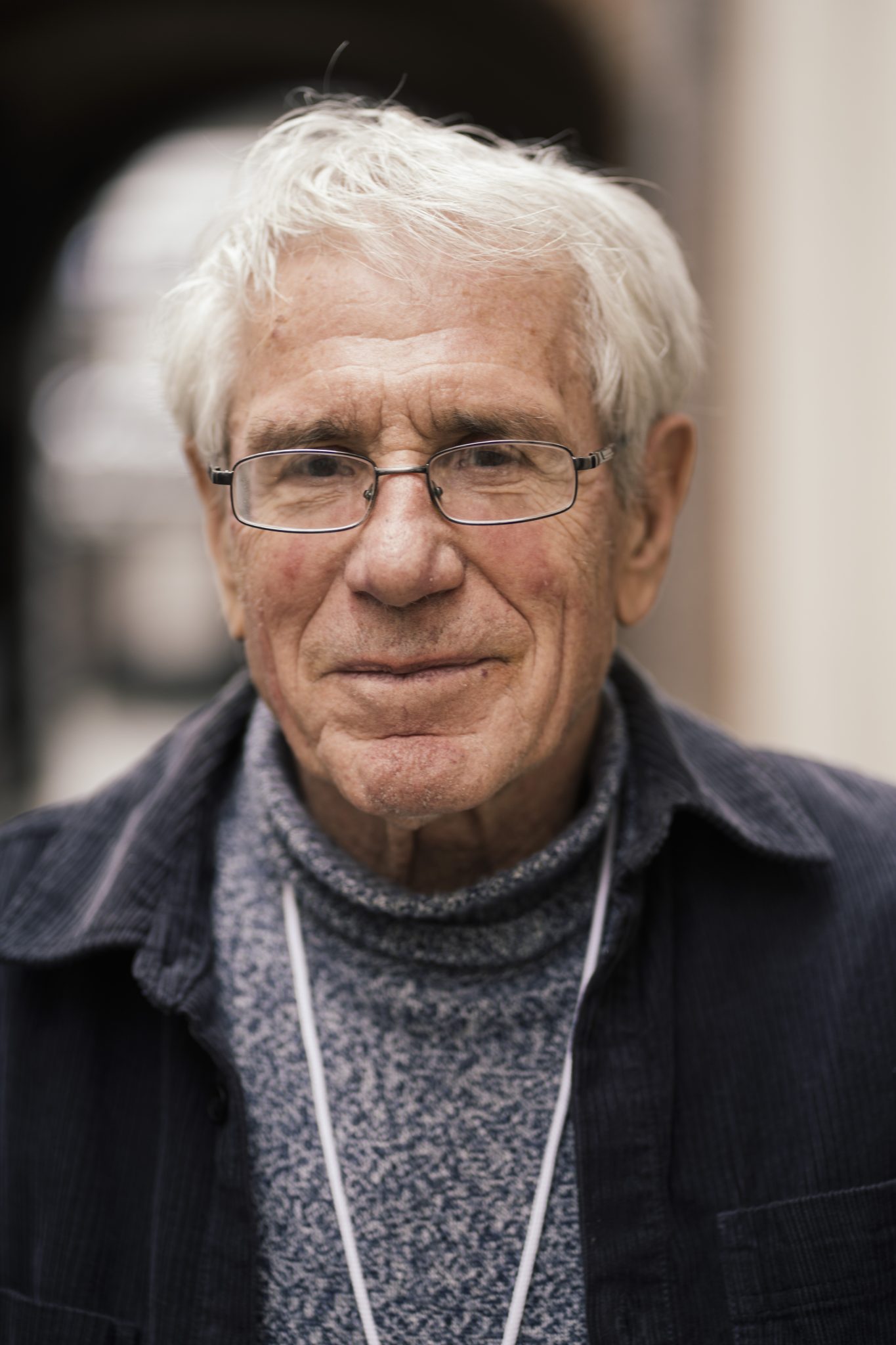

Želimir Žilnik, a filmmaker and demystifier

The 16th edition of the One World Romania International Documentary Film and Human Rights Festival (March 28 – April 9) had Želimir Žilnik, one of the most prominent and provocative directors of socio-political film and a rebel of Yugoslav and post-Yugoslav cinema, as a guest of honour.

The OWR selection included a retrospective of 14 short, medium and feature-length films from different stages of the Serbian director’s career, spanning five decades and totaling over 50 titles (fiction, documentary, docudrama).

Born in 1942, Želimir Žilnik lives and works in Novi Sad. His films have been selected at some of the biggest festivals in the world, such as Berlin, Toronto, Rotterdam, and Oberhausen. His debut feature film, Early Works (1969), about a group of young people who want to start a revolution but discover that real life is far from how is depicted in the books, was awarded the Golden Bear at the Berlinale, after being the subject of a trial in Yugoslavia.

Along with filmmakers such as Dušan Makavejev and Aleksandar Petrović, Želimir Žilnik was part of the so-called Yugoslav Black Wave, a film movement of the 1960s and early 1970s, known for its unconventional style, dark humor, and critical view of socialist realities.

After his first works were suppressed by the communist authorities, he exiled himself for a brief period, in the 1970s, in West Germany, where he made films critical of the migration system.

The power to observe and extract fascinating stories from the lives of ordinary people is a common trait of his films.

“Žilnik has been a deconstructor and a demystifier throughout his career, from his political stances to the film style(s). Žilnik’s cinema is a vast playground where he stubbornly refuses to submit to form and uses film language as a tool to serve his ideas and political questions, to which he remained loyal and consistent throughout his career,” as described by One World Romania in presenting his retrospective.

Given his presence in Bucharest, I used the opportunity to invite Želimir Žilnik for a talk for our column of in-depth interviews with established filmmakers. We started with the war in Ukraine and the incredible story behind his best-known effort, Early Works, and ended up looking into his inclination towards experimenting and low-budget films.

Because in your films you spoke, among other themes, about the traumas from this part of Europe, I want to ask you how you see the Russian invasion of Ukraine and also what the Serbian people think about this war. What we see from the media is that an important part of Serbian public opinion is pro-Russian.

Of course, everybody is trying to follow the information about this war. I think the general opinion is that actually the war in Ukraine or, more precisely, Russian occupation is a danger to the destiny of our planet and everybody’s actually very shocked. Of course, if you analyze the situation regarding political parties, you would find basically two groups. One is so-called pro-democratic and of course anti-Russian war and pro-solidarity with Ukrainians and the whole politics of the NATO and Western countries. And I would say there is only a minority of people that are actually these pro-Putin fanatics, and some of them are from the previous communist regime.

Therefore, I would say that the narrative that most Serbian people or people from ex-Yugoslavia are pro-Russian is simply not factual. Only a minority is. And one reason for this position is represented by some wounds and bad memories from the NATO bombardment of Serbia which happened in 1999. But I think that those who stand for that reason on the Russian side are somehow lying themselves. Why? Because they forget that before the NATO bombardment, there were months and months of negotiation with Serbian president Slobodan Milošević, who was told that what he is trying to do smelled like genocide. But he continued to clean Kosovo and then bombardment started.

What we see now in Serbia, a thing which is maybe not happening in other countries, is that both Ukrainians and Russians are coming as refugees. Both have made organizations of solidarity. And the number of both ethnic groups is around 80.000-100.000 people. Ukrainians and Russians are marching together on the streets of Belgrade shouting “Stop the war”. Many of the refugees, of which some are experts in digital technology, are opening businesses. So what we see is that both groups are well received. I did not read in the newspapers and I did not see any sort of hostility and anger either against Russians or Ukrainians.

Would you agree with the opinion that your cinema is political? And what do you understand by political cinema?

Well, when I plan to film some topic I do it actually to capture and to save from forgetting what is happening around me, the events that are going on, if people are either relaxed or nervous, and then also how the regime reacts. And in many situations, it reacts completely destructive or anarchistic. So, for instance, the time of transition (i.e. after the fall of communism). In some European countries, this transition to democracy was finished successfully and in a normal way, with the exception of some people from secret police violating human rights. The borders were opening, people were given the right to travel and to choose their profession. But in our country this transition was confusing.

In the power structures of the state, there were those people who had been hardcore Stalinists and who did not have the moral capacity to rule like the warriors in the Second World War, who could say they fought the fascists for four years and in the end, with the help of Russians, they won the war and pushed the fascists out of our country. So these bureaucrats, who were the third generation of bureaucrats, after Tito and his team, have been the worst dogmatics and tried to apply Stalinism directly. This insane Milošević sent a delegation to ask for help from the generals who were making the uprising against Boris Yeltsin (i.e. former/first president of Russia, from 1991 to 1999). It is not understandable to anybody normally. And, of course, in this situation, you think you are living in a very weird moment. People are in fear and confusion.

How could you react? In those times I was reacting by going with the camera in the streets and trying to make some sort of reflection with my comments. For example, in 1993, I made Tito’s Second Time Among the Serbs, in which I filmed an actor playing Tito discussing with people on the street, then I made a feature fiction, Marble Ass (1995), which was also reflecting the time, and a short documentary about the biggest demonstration against Milošević, Do jaja (1996), which was shown by the most important international news services.

You experimented your entire career, either with the subject of your films or with the form. You shot on film, on video, then on digital. You made films both for cinema and television. You made fiction and documentaries and a mixture of them. You made feature films, but also a lot of shorts. Could you explain this taste for experimentation?

It is also the question of what was the destiny of my first films. You see, I started in ‘66 as a documentary filmmaker. At that time, we had to film on 35 millimeter, which was very complicated because of the cost of negative and also because of the very small number of 35-millimeter cameras that were present in the city. At that time, a 35-millimeter simple camera cost like today’s car, and a bigger camera, with which you could also capture sound, cost like a Rolls Royce car. So there were only two or three of these cameras in Belgrad. It was very exclusive. At the same time, documentaries were something that people were watching more than today, because in commercial cinema before feature films were always documentary short films, and the regime preferred to be short films from the country.

But very soon the situation started to be different, with the changing of media, when these new cameras appeared, first of all, betas. And then these simple video cameras expanded, and that was when the whole medium exploded because filming became more accessible and easier. And, at that moment, because I could not wait to get a good camera, but also because I was interested in short films, I started to work on this new medium.

Your first feature film and the most famous one, Early Works (1969), has a spectacular background story, also because it was the subject of a trial at that time. Why was it considered so dangerous?

The film was produced by Avala Film, the biggest studio in the country. It was produced on their initiative because I was successful in documentaries. They said: “Žilnik, you should make your debut, low cost, and we will help you”. So I made it. Before distribution, the films always went to some sort of censorship and some functionaries were watching them. In the case of my film, they said it can go to the cinema. So it was run for four months in the cinema, and the producer was very happy because we already returned the investment. But one day he asked me to go to the studio. I went there and he gave me one piece of paper and told me to sign it and that it was very urgent. “What is it?” He said it is information to the media that our film, Early Works, which is now in distribution, is not the film that we finished, it is a film that was stolen, and that our premiere will be in six months. I said: “Comrade, you must have been drinking too much alcohol”. He replied: “Don’t be stupid, HE has seen the film and HE was very angry and stopped the projection after 15 minutes”, and he pointed to a picture of Tito on the wall. I said I don’t believe him, and then he called the man who did the projection on 35 millimeters, because he was also working for Avala Film. So the man came and said: “Tito stopped the film. He did not comment much. He just lit a big cigar and said he doesn’t understand what those idiots in the film want to do. Tito doesn’t like these modern films. He likes most partisan and cowboy films and for him, the best entertainment in the evening is mariachi music from Mexico. So it is not only about this film, he stopped every single so-called modern film because he is an old man”.

Then the producer said he has to call the public prosecutor, to whom he told that I do not want to sign that paper. Then this public prosecutor said he is sending the accusation for the film to go to court, so the police will come. Police came and I was prepared to go to jail, but the police said my name is not on the paper and that they have to take only the prints of the film. Avala Film did not want to give me any lawyers, but luckily I finished Law Faculty. I went to the court. I showed my diploma. I saw the prosecutor make a very primitive accusation, very much in the style of Andrey Vyshinsky in Russia in the 30s. So I was shouting at him: “Comrade prosecutor, you either are not a member of the Communist Party or you are someone who did not read our Communist Party program, because you are against the freedom of art. Do you know that there is a big chapter about freedom of art? You are a Yugoslav Vyshinsky. Comrade judge, you should send him to Russia”. I had to shout because for me it was a matter of life or death. Luckily, the judge didn’t like the prosecutor either, because of the primitive way in which he made the accusations.

You see, the prosecutor said the film is against working people in factories and against peasants in the fields. Stupid. So the judge needed to stop him. He took a break. There were many people, many journalists and many intellectuals present. While I was going out, the judge told me: “Why are you shouting, don’t you know that the film was seen up there?”. I said I have heard that, but I also heard that there was no reaction from HIM. We could not say Tito’s name. “If the reaction would have come from HIM, I would not be here, I would be in jail”. He said that I was right and asked me if I had any witnesses. I said yes – all the departments from Avala Film: “I will call them, so they will have to defend themselves”. So the next day, he was listening to these people and the prosecutor did not have any arguments. Then the judge said he wanted to see the film. After that he told me in front of all those people: “You made a very boring film. I had a hard time trying not to fall asleep. It is not a danger for our country, for our ideology, it’s actually a danger for you, as you will be hungry in your profession. Better change the profession”. Then he said to the prosecutor: “Comrade, stand up. If you think that this boring and unsuccessful film can ruin our socialist system, you are the first who doesn’t believe in that system. And you should also change your job because as a prosecutor you have to defend our country, not create confusion”. And he said the film is free. He wrote it. Then the film was selected in Berlinale, where it won the Golden Bear.

You chose to work specially on low-budget films and you rejected your entire career the so-called “quality cinema”.

Well, you must understand that I am from a generation that actually learned what was happening in the world on the screens of ordinary cinemas. You see, when I started going to the cinema, at the end of the 40s and the start of the 50s, in Yugoslavia they just finished showing Stalinist films and shifted to openness to the West. So in our towns it was somehow better than in Germany or England. Why? Because Italian cinema, French cinema, South American cinema, Scandinavian cinema, they all saw our market as a small one and they were sending Fellini and Bergman films first in our cinemas, you understand.

So when I went to Germany, after some years, they still did not see all the Godard or Truffaut films. Western countries may have considered some of them propaganda, while the bureaucrats from our country thought we should see how Western life was going on, because some of these artists were critical towards western societies. Just think about neorealism. We saw all those films. That is what made me interested in films.

Film is this powerful tool and powerful media which reflect differences in cultures and in characters and the relation between men and women. Sometimes, of course, they can provoke debates. I started doing mostly low-budget films, so I did not have any financial risk. When you are making these big-budget films, your hands are tied, because you have to return the money, and then you can not provoke debates. These low-budget films have been very inspiring for me.

Journalist and film critic. Curator for some film festivals in Romania. At "Films in Frame" publishes interviews with both young and established filmmakers.