Ana-Maria Comanescu: “I’m fascinated by the escapism of cinema”

Ana-Maria Comanescu is part of a young generation of Romanian directors that we will definitely hear about in the coming years. Rather interested in a certain type of independent American films, and less by the Romanian realism, she seems to propose a different kind of cinema.

Born on January 14, 1993 in Bucharest, Ana-Maria Comanescu studied at “Saint Sava” High School, in the philology class. Between 2011 and 2014 she studied film directing at UNATC, where she then followed a master’s degree (2014-2016).

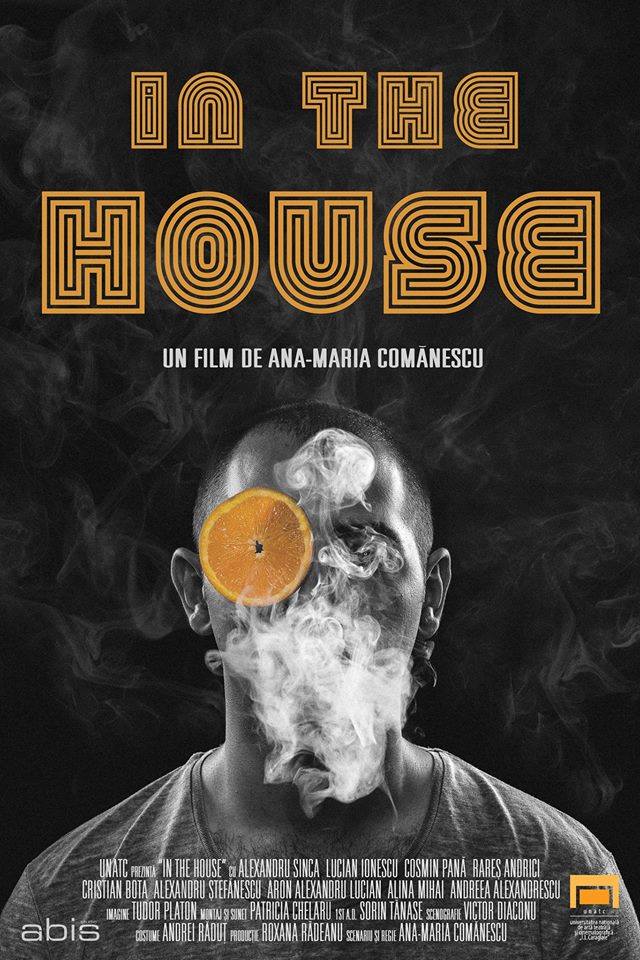

With her graduation short film, In the House (2014), she participated in several national and international festivals and was nominated in the “Young Hope” category at the Gopo Awards. The film is about a group of friends who throw a party where one of them admits that he just killed someone in a car accident.

Her next two projects came out in 2015, the short documentary Play It Again, Xiamen, made in China, and the first fiction short film during her master’s, Second Look, which was also selected at several festivals, including Premiers Plans in Angers. It’s the story of a couple whose problems surface when, during a trip, they pick up a weird hitchhiker.

The short film she made for her master’s degree, Sex, Pipe, Omelette (2016), is a vibrant comedy about two neighbors who come up with a plan to exchange wives for one night.

Since 2017, she has been working on her feature film debut, Horia (produced by MicroFILM), which she intends to shoot in 2021. It’s a road movie with a teenager traveling across the country on a Mobra motorcycle.

How did you become so passionate about film that you decided to study film directing at UNATC?

I have loved writing and drawing since I was little. Those were my main interests. At the age of 13, when I was in seventh grade, I began to discover the good, classic, must-see movies. I really liked them. I also remember that I started going to the theater with my friends, and not with my parents as I used to do before. There was this play at the ACT Theater, called Theatre creator (directed by Alexandru Dabija), which I saw 7-8 times, I think.

I thought that being a director would be very cool. At first, I was more inclined towards the idea of being a theater director, but then I thought that film could offer me more. I saw it as a world that offers you the opportunity to express yourself in many more ways. So there I was, totally hooked on this idea. I remember going and telling my family: I know I’m 13, but I’d like to be a film director.

Then I did all sorts of crazy things: I wrote all kinds of stuff and made my schoolmates play the characters while I filmed them. I was pretty set on that. In high school, my Romanian teacher, who was also our head teacher, was including examples from cinema when talking about literature, and so he tried to offer us a wider cultural landscape. We also had an elective class on cinema with our art teacher, where we watched and analyzed movies. I wasn’t exactly a movie buff, but I was interested in the idea of film as a means of expression.

You understood that film isn’t just a story, but rather that it’s a more complex thing that involves a team effort and that it’s an elaborate process.

I really wanted to be part of a film shooting. I used to imagine myself doing that. I always wanted to be on set, to see exactly what is going on. When I was in eighth grade, I was constantly watching making-ofs to see how movies were made.

But where did this passion for film come from?

I liked visual things, painting, and taking pictures. Like any 14-year-old girl, I was walking around with my DSLR around my neck, taking pictures of flowers in Cismigiu Park. On the other hand, I really enjoyed reading and writing. So I felt that film combined all of these and I could have a little bit of each.

Did you have any hesitation in choosing to make film?

Absolutely none. When I entered high school, I told everyone: I’m going to UNATC, I want to be a film director. My mother asked me if I didn’t want to apply to another college as a back-up. I said no. I got upset, we argued, I was very offended.

Did you take the training courses for the admission exam at UNATC?

I did. I remember that, after our high school graduation, in July, all my colleagues already had their admission exams for college, so they went to the seaside where they had fun, took pictures. My admission exam was in September. So I spent the summer watching three or four movies a day. I overdosed because, for example, I hadn’t seen anything by Herzog or Angelopoulos.

I had comprehensive files with info on each director: what movies he made, how he made them. I studied for the admission exam just like for the baccalaureate. I wanted to be bulletproof, so that no one would comment on anything. I don’t remember how the oral test went, but for the written part I think I wrote five pages about a sequence in Once Upon a Time in America. And my handwriting is small, like a true nerd’s (laughs). I got a high grade, there was no way I wouldn’t have been admitted.

You actually got the highest grade. How were the three years of college?

I remember how much I wanted to learn the cinematic language, to learn about the whole process. And as a nerd whose main objective was to learn, I was super disappointed. I felt like I didn’t fit in. And the truth is, I don’t fit into the bohemian artist profile. But in college it’s a given. You are encouraged to be like that. Everyone is trying to stand out in a way or another, to do something special. Our class was quite diverse, we were 21 people at film directing, which is a lot.

I tried to learn everything that could be of help. And see what I could do with that. I tried to do things my way, but I was intimidated by the fact that I couldn’t find my place in the group. In high school I was in an all-girls class. We came to school wearing make-up, in skirts, and we complimented each other. At UNATC, I felt people were looking at me differently, for example just because I dyed my hair blonde and I was wearing make-up. Honestly. I felt that I wasn’t given enough credit, and it bothered me very much. At one point, I started having small complexes, but in time I got over them.

But how did college help you?

First of all, it helped that no one had a problem with the fact that I started working in college. The school schedule wasn’t a crazy one, so I had enough free time. Then, in the third year, I attended all my colleagues’ film projects. I worked in every department on the set. I helped with everything I could. During my master’s, I don’t even know if I’ve ever been to classes. I was already pretty upset. I realized that college didn’t offer me what I needed. But maybe to others it was the right opposite. Still, I did have the opportunity to make some films, to get feedback from some people, and to get to know my generation, which I worked with afterwards.

After you finish your studies, what happens? What’s that moment like? What do you do next?

I didn’t have that: done, it’s over, and now what? I was already working on film projects, as an assistant director, but also on commercials. I did everything: ads for dating sites, frozen vegetables, lamps, furniture factories. And it helped me a lot, both financially and as a workflow. After that it was quite easy, because I already knew people.

Maybe because I had this idea that I was seen in a certain way, I didn’t want to end up making films without knowing my stuff and someone from whatever department telling me that we can’t do a certain thing. I wanted to be able to say: yes, it can be done, I’ve already seen it. Might be my need to feel in control.

I had colleagues who used to say that if you take assistant jobs now, you will only be seen as an assistant. But I don’t think it’s true. After all, people will see you the way you allow them to see you. So I’ll be an AD up to a point. Not until I’m 40, I hope. But now, when I’m twenty-something years old, I can do it, because I have the energy to be on set all day and deal with all the crazy people screaming at me.

In the House looks like a typical UNATC short film.

Yes, for various reasons. You’re forced to film on a school set. You are forced to shoot on a 16 mm black and white ORWO film. But, for better or for worse, I made my peace with it. I was upset when I made the film, because I felt that, since it’s a party, it should be much more colorful. But now, looking at it, I think it works, it has unity.

Although different in style, your three short films are similar. I mean they might come as lighter films, but in depth they talk about some serious things. How did you start writing them? How did you develop them?

The first two are based on real events, based on stories I’ve heard. For In the House, I already had the context in mind, this party with several young people. I grew up in Bucharest. Smoking around the block, that was something I used to do. Hanging out with this type of gang. I know a lot of these guys. I was very familiar with how these parties are thrown in the neighborhood. It’s just an apartment party. Then, one night, in a parking lot, I happened to hear someone saying that one of his pals was racing cars with another guy and ran over someone, and that he was going to go to jail. I realized that this casualness in talking about such things can only exist in a group of friends. So I wanted to combine the two contexts.

For Second Look, someone told me about an incident with a hitchhiker who turned out to be quite weird. Then I thought about a cool, hip couple who actually have a lot of prejudices, and how these two attitudes would come into conflict.

Then, for Sex, Pipe, Omelette, I was inspired by a short story by Roald Dahl. I have always been curious about the lives of people who have been married for a long time, as well as people who are swingers, have open relationships. Both options seem like they require a high degree of self-awareness, and they don’t really seem to be for everyone. That is why I’m curious to observe unconventional forms of marriage, because I wonder how people get there. I really like Roald Dahl, I have been his fan since high school. People know him for the children’s books he wrote, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory or Matilda. But if you look at them, you realize that they are hiding some very dark things about human nature. But he also has novels and short stories for adults. The novel My Uncle Oswald is really awesome. It’s an incredible story. And I’m shocked that no one has thought to adapt it into a film yet.

I knew I would never be able to make a Roald Dahl short story after finishing college because of the copyright issues. And then, I wanted to make a story that looked like it could happen anywhere. Something universal. I like stories that create a small universe of their own, that place you within a convention. There seems to be a lack of this kind of approach in today’s cinema, almost all films being very much anchored in the social or political context. I’m fascinated by the escapism of cinema. And I tried to see what it’s like to make a comedy. But I don’t think I could ever make a comedy where it’s just about making people laugh. But a movie with comical touches, yes.

It’s a different kind of film from what your colleagues were making then – colorful, with a certain assumed artificiality. Why did this area appeal to you?

First of all, I wanted to try various things in college, regardless of the outcome. I wanted to take advantage of that time because I knew there wouldn’t be that much freedom to explore after that. The moment you have a production company and you receive state funding, in my opinion there isn’t much place to experiment. I wanted to see if I could build this kind of stylized and colorful world at the surface, with something terrible hiding underneath. That’s what I wanted to achieve: a contrast between the beautiful exterior and something rotten underneath.

I’ve always had a fascination with the American suburban drama, even if I haven’t made it to America so far. And I mean those American suburbs where all the houses are the same. Such residential areas have begun to appear in our country as well, where everything looks the same. And there always seems to be something hidden there. From Blue Velvet to American Beauty or The Ice Storm. I really liked those kinds of movies that show that things aren’t really that pretty on the inside.

Your future debut seems inspired by American cinema as well, not just because you want to use a lot of music, but it’s the very idea of a road movie, an adventure film with a teenage protagonist. What’s the source of the script and how did you come to it?

The film is a road movie, but it’s also a coming-of-age story. They work together, not separately. It’s an actual journey, but it’s also the inner journey of the character who, if you will, discovers the world for the first time. It’s his growing up story.

As a child, I traveled a lot with my parents by car. I didn’t have a tablet or a smartphone, so I was always gazing out the window. For me, these trips are some of the most beautiful memories I have and I saw no other way to make my debut than through a trip.

When I was 21-22, I went to China for three weeks to make a documentary, which was more of an experience (Play It Again, Xiamen, 2015). I went there with some Romanian colleagues, but it was practically the first time I was traveling alone in a completely different part of the world.

In China, especially in the southern region where I went, I felt like I was on another planet. I saw a different world. It was my coming-of-age story. I remember very clearly that when I returned home, I was extremely aware that I came back as a different person. I realized how true this cliché of getting out of the comfort zone is. And I got out of my comfort zone quite brutally.

The weather was so hot. Then, being blonde with green eyes, people looked at me like I was alien and took pictures of me. It was so weird. So many crazy things happened to me there, I had so many adventures. I realized that this means to grow up, when you are taken out of your comfort zone so much that you can no longer connect with the person you were before, and you start to open up and be something else. You become an adult.

You realized that such a transformation could be a good subject for a film. Then you talked about the memory of your childhood travels.

I wrote Sex, Pipe, Omelette together with Andrei Hutuleac. And the plan was for us to write a feature film together as well. He came to me with this idea: a guy, about 40 years old, crossing the country on a Mobra. It was just a seed, which grew into the script that is now. Our schedules were totally out of sync, so he told me to continue with the script by myself. I said, okay, but things will probably change. And I realized that the story must be about another type of character, about a character who is growing up. He’s not exactly my age, but somewhere around. Something clicked in my head and suddenly the script began to take shape. Then, step by step, other things piled onto that.

Speaking of the way people perceived you in college, of how different Sex, Pipe, Omelette is from other films, of your future debut: it seems that you are looking for a different angle in approaching your stories compared to the Romanian film we grew accustomed with in recent years. I don’t know if it’s a conscious decision. Where does it come from?

I believe that this era of the great directors, such as Puiu and Mungiu, came out very organically. It makes sense. That’s how film developed in our country. There are some great movies out there, I wouldn’t say otherwise.

The problem is that after that, a lot of people tried to adopt their style, for reasons I never understood. I didn’t understand why you would want to make movies like others, when it would be much more efficient and healthier to try to make them your own way. You might make mistakes anyway and not get the desired result, but I think it’s important to feel like they’re your own mistakes. Like I said, I don’t really belong there. It’s not an approach I can connect with, to tell the truth. I didn’t come from a poor family. I didn’t go through a horrible hospital experience, to see how defective the system is. Maybe someday I will, and I will start making movies like that.

I like movies that don’t tell overly dramatic stories. But the things that happen have to change something inside the characters. I’ve always liked character-driven movies. That’s what I’m into. Now, if I look around, I could say that the films I make are different from what’s usually made here. But that wasn’t my starting point. I only tried to do something that I could watch and say it was what I wanted to do in the first place.

Something to be happy with. After all, it’s less important if the first films don’t pay attention to social issues, to very harsh realities.

Some believe that a film needs to do that. There is this strong opinion out there that film should address and examine certain issues and that it’s the director’s duty to turn his attention to these things. But I see change as coming from self-awareness, most of the time. So that’s what I want to turn my attention to, at least for now.

So still going through inner searches. But have you figured out which area you like best?

Like I said, character-driven movies. I like Todd Solondz, Hal Ashby or Mike Leigh. The kind of authors whose movies aren’t extremely dramatic, but talk about deeper heavy things. Or Paul Thomas Anderson. He’s a god to me.

How do you see the relationship with the actors? How do you work with them?

Well, I’m not a spontaneous person. I try to be in life, in general, but it never works out. Spontaneity is not my thing. So I try to get everything in order before the shooting starts. I care a lot more about the chemistry I have with the actor, than their actual performance during the audition. In some cases, in the past, I didn’t consider this aspect that much and then I was sorry. Since then I’ve realized that it’s very important to have chemistry with the actors. And there should be mutual respect. These are essential.

Working a lot as an assistant director, I noticed actors come in different shapes. There are actors who learn their text and are very eager to do their job, they come with suggestions and try their best. And there are actors who think it’s enough to be talented. I mean, it’s great to have talent, but it’s not enough.

I do my best to make it clear what I want them to do in a certain scene and I try to get a lot into what the character is feeling at that moment. I’m not telling the actor how to say the line. But I try to push him somehow, to give him the means to get to what I want, but to on their own, so that it feels organic. I strongly believe in rehearsals.

For your debut, you will work with young non-professional actors for the leading roles. What challenges do you think you will encounter?

Since I don’t have much experience, the hardest part will be figuring out what that person needs. On the one hand, I worked with actors who did great, if not perfect, on the first take, but after that, as we did more takes, there was something off in their performance.

On the other hand, I worked with actors who needed a few takes to warm up. So when you have these two types of actors together in a sequence, it’s quite difficult. I’m actually afraid of this situation, so I do my best to understand, to listen, to be open, to see how that person works. To figure out what their acting style is, so I can understand what I need to offer to them. I think you need to help them, give them the tools. With someone who hasn’t acted before, that actually helps me, because they don’t have some fixed ideas or patterns that I might have to tear down or change. Simply put, it’s tabula rasa and we’ll build from there. That’s how I imagine it will happen.

For this type of roles and characters, I suspect that charisma and authenticity are very important. What are you looking for?

When you have an unknown actor, so you can’t use their name to promote your film like you would if you had a famous one, it’s important for the protagonist to have that particular charm. I really think a protagonist should have that “je ne sais quoi”. I wouldn’t be tempted to watch a movie about just anyone.

What do you mean by that?

It’s very difficult to give a definition. If I’d known what it means exactly, the casting would have been over a long time ago and things would have been much clearer. It could be the way he speaks. For example, my character is an atypical kid for a boy, meaning he’s quite romantic and dreamy and shy. At the same time, you have to feel that under this shyness there is a personality that has not bloomed yet. And he has to change, to flourish over the course of the film. That’s what I’m looking for. I’m looking for a person whom I can be fond of, first and foremost. To enjoy watching him, because that’s the nature of this film. And to feel that he has the potential to evolve as a person, to open up, to show more.

In your short films you used music, and in your debut film you also want to have a lot of music. What does music offer you?

Music is a very important part of my life.There isn’t a day I’m not listening to music. I see it like an essential tool in seducing the audience. If my goal is to subjugate the viewer, I automatically try to use all means. Emotion in film is very important to me, so then I expect music to either say something about the characters or give the key to the scene.

You can’t run away from the fact that film is a trick. I own that and I try to use all means. Yes, music does manipulate, but cinema itself manipulates. In my debut I would like to use both a soundtrack and an original score. It’s a different kind of process. Combining them is the right fit for this film.

How do you think being a woman influences your career as a director?

Surely, when you’re a young and pretty girl, people look at you in a certain way, they notice that. Some may develop ideas or behave differently based on this observation. Or not. It depends on everyone’s education and background. I’m not going to pretend that these things don’t happen, but at the same time the fact that I am a woman is not something I want to parade around with, a medal.

Like anything else, it has its advantages and disadvantages. But things are becoming better. I find that a lot of people are focused on giving women a chance. But I would rather be seen just as a director, not as a female director. I don’t see the relevance of adding “female” to the general term “director”. Actually, this is the point we need to reach, and that’s what we should be aiming for: let’s stop saying “female director”, with an emphasis on “female”. “Director” is enough.

I’m asking you because you may have faced some prejudices along the way.

Oh, definitely. There are misogynistic people in cinema, as there are in life. Personally, I try to avoid them. I’m not trying to do things in order to prove anything. If I’m treated unfairly and someone has an attitude towards me that bothers me, I will definitely say something about it. But more than that, I don’t know. And I don’t believe in the cliché that women come with a special sensitivity either. I think there are sensitive male directors, just like there are less sensitive female directors. It’s a discussion I usually avoid.

What do you like so much about film directing and cinema? Why do you like making films?

I like to build and tell a story. I really like the idea that a person could walk into a movie theater to watch my film and forget about their problems for two hours.

I realized that the films that impress me the most are the films where I get the need to talk to the screen, to the characters, this need to just get inside the story. To feel that you are completely subjugated by the film – that’s the real art of cinema for me. It’s hard to get there, but that’s what I’m trying to achieve.

It’s not some breakout from immediate reality, but rather an instrument of self-knowledge. It may sound cheesy, but when a film strikes a chord in you, you automatically become aware of it. And maybe you forgot it’s somewhere in there, because you’re too busy with everyday things. But the film reminds you that it exists.

Banner photo credits: Boróka Bíró

Journalist and film critic. Curator for some film festivals in Romania. At "Films in Frame" publishes interviews with both young and established filmmakers.